Tribal Tourism Reimagined in the 1990s

Welcome back to the next installment in our Decades of Seminole Tourism Series! We only have a few decades left to explore as we get closer to the Seminole tourism of today. This week, we are looking at the exciting and action-packed 1990s. The Seminole Tribe would reinvest the financial gains of the late 80s and early 90s into Tribal tourism. They would diversify their cultural attractions and lean heavily into ecotourism during this decade.

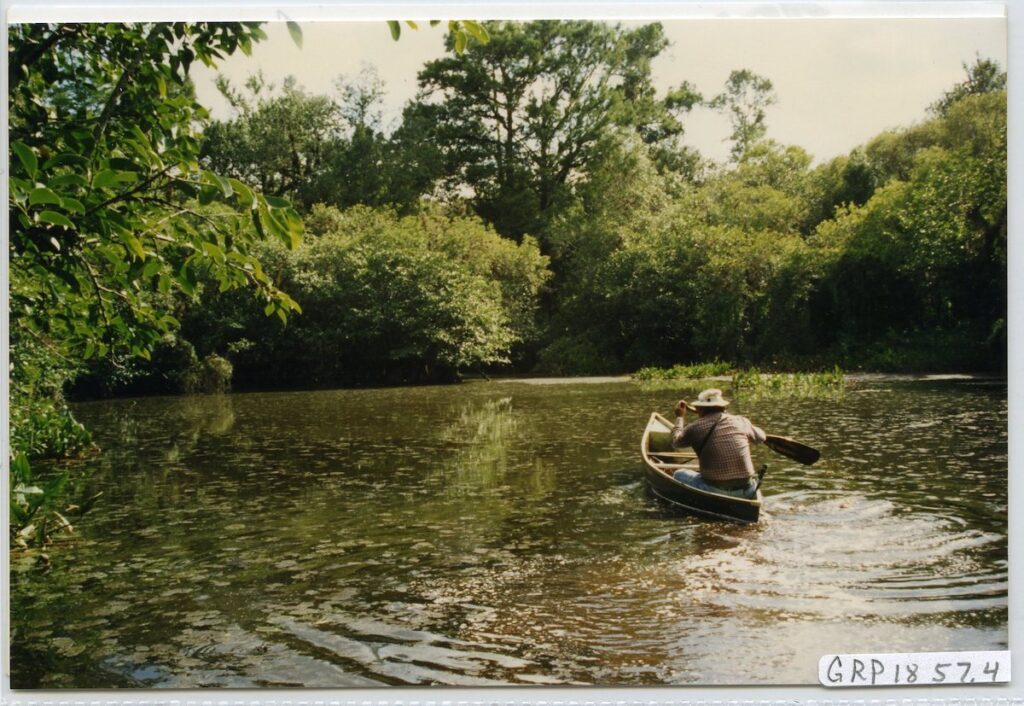

Below, you can see an unidentified man paddling a modern canoe on the Kissimmee Billie Slough in 1995. It is located on the Big Cypress Seminole Indian Reservation.

The Seminole Tribe Prospers in the 1990s

Coming off the bingo boom of the 1980s, the Seminole Tribe of Florida prospered. By the 1990s, the Seminole Tribe would have several successful bingo halls across multiple reservations. These gains reflected financially, and “in 1997, the Seminole Tribe approved a fiscal year 1998 budget of $127,881,000” (West 229). With this new fiscal flourish, the Seminole Tribe was poised on the brink of their most profitable moment in history. So, they began reinvesting in their community, centering community services and the needs of the Seminole people. Many, like Chairman James E. Billie, were also anxious about this financial turn of events and how it may impact Seminole culture. Billie also “created educational programs that stress language, history, and culture at the Tribe’s Ahfachkee School on Big Cypress” (West 236). Additionally, Billie had a noted interest in investing in Seminole tourism enterprises. Billie “was [a] consistent advocate for tribal tourism” (West 234).

Over the past year, we have explored numerous ways Seminoles used tourism to gain financial independence. In the 1990s, there came a distinct shift towards using tourism as a tool. The intention was to protect, share, and educate about Seminole history and culture on a larger scale. Cultural and ecotourism attractions obviously still held a financial component. But, with the financial backing of bingo halls and smoke shops, Seminoles were able to share the Seminole story and culture in an unprecedented way. With the Tribe’s interest and support, “tribal tourism was thriving. Far from being abandoned in the wake of new economic booms, the tribal financial backing of new and old tourist venues saw a great resurgence…. The revenues of smoke shops and gaming are being reinvested in ventures that can compete with the world’s best examples of cultural attractions and ecotourism” (West 233-234).

Seminole Ecotourism

During the 1990s, Seminoles began to lean into cultural and eco-tourism in a big way. Previously, we touched on ecotourism in Indian Country. Especially, how important it is to be an ethical ecotourist when interacting with Native communities. We defined ecotourism as the thoughtful, responsible travel to natural areas. It centers the needs of the environment and the well-being of Native communities.Thus, education and critical thinking are at the core of ethical ecotourism.

As the Tribe reinvested in its tourism offerings, education about their cultural practices, and by extension their relationship with the Everglades, became increasingly important. These grander offerings struck a chord with tourists, as “In Florida near the end of the century, ecotourism was the buzzword of the day. It was popular with European tourists, who were especially interested in ‘the State’s natural attractions, such as the Everglades” (West 234). With this heightened interest from tourists coming in, Seminole Tribal tourism flourished. Billie Swamp Safari, located on the Big Cypress Reservation, opened in 1993 to much acclaim. An eclectic mix of wildlife sanctuary, eco-park, and thrilling adventure, Billie Swamp was an enticing lure for tourists. Billie Swamp offered swamp buggy and airboat rides, camping, and wildlife shows.

Other Seminole ventures included promoting “cultural activities such as craft production and sales, alligator wrestling, zoo keeping, the wearing of patchwork clothing, canoe making and canoe demonstrations, traditional foods, and the telling of Seminole legends” (West 234). Notably, they also included an educational component. Tourists could learn the Seminole story, watch a master artisan make traditional crafts, and eat traditional foods. Below we will talk about three important Seminole tourism moments in the 1990s that promoted this new, further-reaching vision for Seminole tourism: the opening of the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum, the reopening of Okalee Seminole Indian Village, and Discover Native America.

The Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum

Originally conceptualized in 1989, the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum opened its doors on August 21, 1997. Meaning “a place to learn, a place to remember” the Museum functions as a resource in and for the Tribal community, a museum open to the public, and a conduit for education, growth, and learning. The needs of the Seminole community are paramount to its mission, which is to “respect, celebrate, and preserve Seminole culture and history.”

When discussing the need for a museum, former Chairman James E. Billie stated “We have lost priceless knowledge of our people because we failed to properly document and store these documents. Therefore, I believe it is time to develop a museum where we can do these things and share our culture with those who wish to know a little about the Seminole.” The Museum is a prime example of Seminole cultural heritage tourism and ecotourism. It features not only exhibit spaces, but also a one-mile boardwalk through a cypress dome, Seminole Village and crafters, and immersive educational experiences. You can learn more about the history of the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum here.

In our featured image, you can see a group at the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Groundbreaking Ceremony on January 28, 1993. Tribal members pictured include James E. Billie, Betty Mae Jumper, and Billy Cypress. Far left to right is Jeanette Cypress, Carol Cypress, Laura Mae Osceola, Louise Gopher, Frank Billie, David Cypress, Mitchell Cypress, Billy Cypress, Priscilla Sayen, Betty Mae Jumper, Juanita Tommie, James Billie holding Micco Billie, and Minnie Doctor. In just a few short years, the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum would open as a fully conceptualized Museum. Below, you can see Bobby Henry leading a stomp dance at the opening festivities for the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum on August 15, 1997. It was taken in the ‘Ceremonial Grounds’ at the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum.

Okalee Seminole Indian Village Reopens

Only a year and a day after the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum opened, the Okalee Seminole Indian Village and Museum reopened. Okalee originally opened in the 1950s as the Tribe’s first, official venture post-federal recognition. It would open and close several times during its history. It is located on the Hollywood Reservation. A Seminole icon, the original Okalee represented the Tribe seizing their own agency in the wake of federal recognition. It was fitting then, that Okalee would reopen in the late 1990s. The Seminole Tribe was again seizing and cementing their own agency in a pivotal historic moment. This new Okalee opened in 1998 and boasted a museum space for artifacts, a full village recreation, and even a 300-seat arena for alligator wrestling shows.

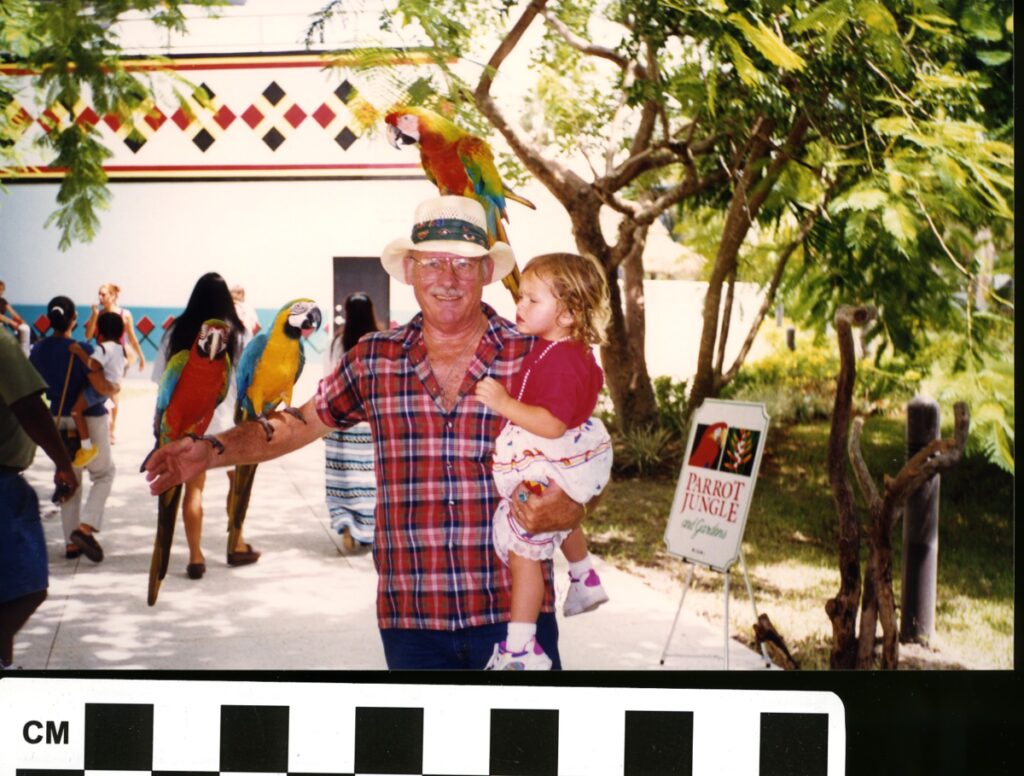

Tribal Board Representative at that time, Carl Baxley, made the renovation and reopening a campaign promise in 1996. In a 1998 Stuart News article on the reopening, Baxley stated “This has been a dream of mine and many others over the years. This will be the best place that people can go, on this reservation, to find out about the history, culture, and current affairs of the Seminole Indians” (The Stuart News, 21 Aug 1998). Baxley also noted that he hoped it would be a “preview,” enticing people to make the 70-mile trek out to the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum at Big Cypress. Today, Okalee is still an important Seminole resource used for gatherings, events, and exhibits. Below, you can see Guy LaBree and his granddaughter at the reopening of the Okalee Seminole Indian Village and Museum in 1998.

GRP650.2

Discover Native America

The same time that the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum was coming to fruition, and Okalee was undergoing its $3.5 million-dollar renovation, another ambitious Tribal tourism event made waves across Florida. Discover Native America (DNA) started in 1992, and was “what was then the largest pow wow east of the Mississippi River… [attracting] hundreds of championship Native American dancers to compete for large cash prizes” (West 258). It was started on the Hollywood reservation with major support from Chairman Billie and the Seminole Tribe. Eventually, it would move around the Southeast as an annual event. Discover Native America was ambitious, featuring alligator shows, dancing, craft demonstrations, and pulled performers from tribes across the United States. Below, you can see Betty Mae Jumper seated in an alligator wrestling pen with a live alligator swimming in a pool. She is speaking to a crowd by microphone during a Discover Native America event.

2015.6.18268, ATTK Museum

In 1999, the Seminole Tribe organized a nine-month series of events that coincided with Discover Native America. This included a three-month exhibit display coordinated by the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum curator David Blackard and Executive Director Billy L. Cypress. This exhibit was “the first major travelling exhibit of tribal treasures to open since the museum was created” (The Stuart News, 28 Feb 1999). Soon, the Museum would expand beyond even their most lofty goals.

Beyond the 1990s

With these openings and events, this new phase of Seminole Tribal tourism found its footing in the 1990s. Centering Seminole culture and history, Tribal tourism would continue to prioritize education and the needs of the community. Increasingly popular, events like these would set the stage for a momentous turn of the century. So, check back in next month to explore the 2000s, where the Seminole Tribe’s bright future continued to shine.

Interested in the rest of our Decades of Seminole Tourism series? Check out previous blog posts on the 1900s, 1910s Part 1, 1910s Part 2, 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting to Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.