Seminole Economic Resilience in the 1960s

Welcome back to our series on Decades of Seminole Tourism! This week, join us as we look at the struggles and triumphs of the 1960s. Coming on the heels of federal recognition, the 1960s was a difficult decade for Seminole tourism, one marked with both struggle and economic resilience as they tried to make their mark as an independent sovereign nation.

In our featured image this week you can see a postcard of prominent Seminole leaders Betty Mae Jumper and Joe Dan Osceola holding up a Seminole flag with a blue background, red/blue/white diagonals and a central Seminole Tribe of Florida seal. They are standing on a grass field next to a chickee, and smiling. On the back, printed in black ink, it reads, “the ‘unconquered’ Seminoles of Florida have preserved their cultural background and have made it available to the public to enjoy and learn at Seminole Okalee Indian Village and Crafts Center, Hollywood, FL.”

GRP1896.100, ATTK Museum

We have talked about Betty Mae Jumper before on this blog. She became the first chairwoman of the Seminole Tribe of Florida in 1967. Additionally, she co-founded the Tribe’s newspaper in 1956, and was a storyteller, nurse, teacher, and matriarch. Jumper dedicated her life to the Seminole Tribe of Florida, and tirelessly worked to improve educational opportunities for Seminole children, Seminole access to healthcare, and the Tribe’s financial situation. In particular, the 1960s was a desperate financial moment for many Seminoles. Jumper’s dedication and work was instrumental in the future success of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, and their economic resilience through the 1960s and 1970s. Above, you can see Betty Mae Jumper with “Princess,” a panther cub, in the 1960s.

Florida Tourism in the 1960s

Florida tourism in the 1960s experienced steady growth, establishing the state as a major tourism powerhouse. A 1970 New York Times article noted that the: “fantastic growth tourist business in Florida in [the 1960s] surpassed any other resort area in the world.” In only one decade, the tourist visitor numbers more than doubled. Additionally, they noted the massive increase in hotel and motel construction to compensate for the droves of tourists. This would feed Florida’s new image: a sun-soaked, brightly colored, tropical haven for travelers that promised an escape from the mundane. This is captured in the postcards of the time, which emphasized and upheld this new image. Around this time, Florida cemented itself as a theme-park capital. Walt Disney World opened outside of Orlando in 1971, after major land purchases and construction dominated the area in the mid-1960s.

During this era, some of the largest draws to the state were the beaches. This was closely followed by state and national parks, which featured Florida’s natural, unique beauty. Everglades National Park officially opened in 1947. The Big Cypress National Preserve would follow, opening in 1974. All of these events bolstered this wave of tourism, enticing visitors to Florida’s beaches and parks. Snowbirds began to stay for months to escape northern winters and fed Florida’s tourism economy.

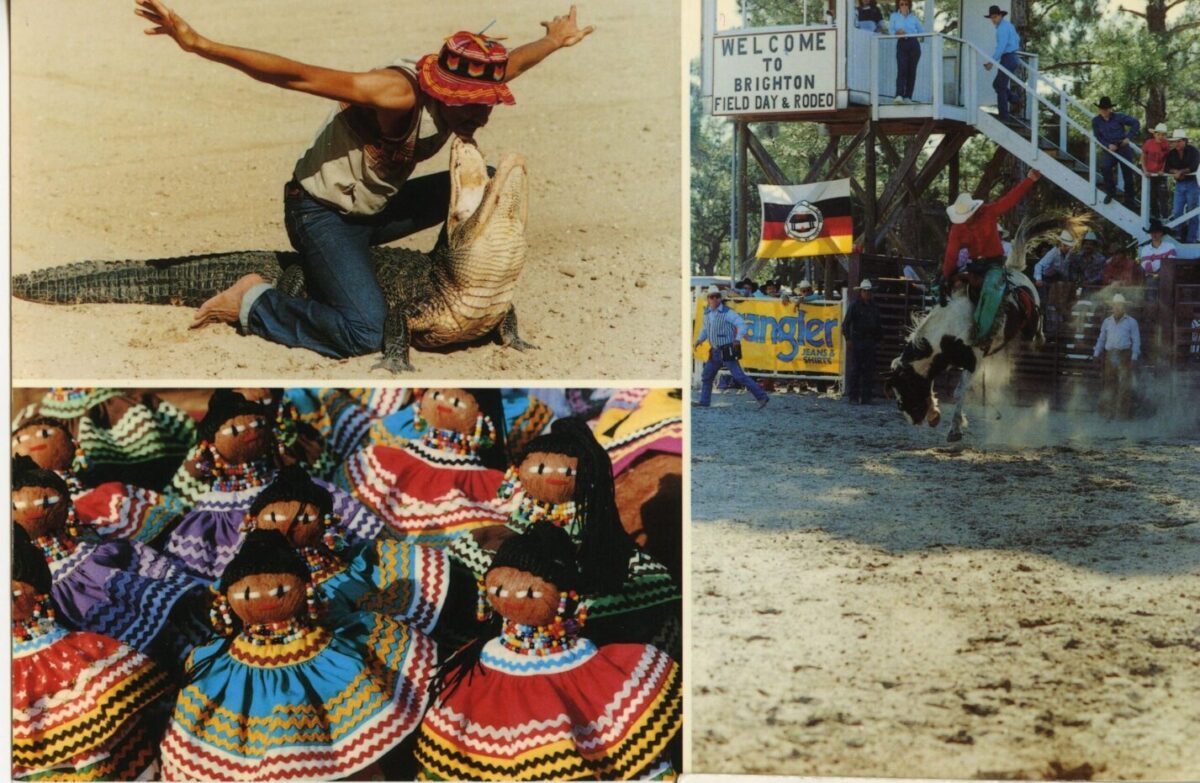

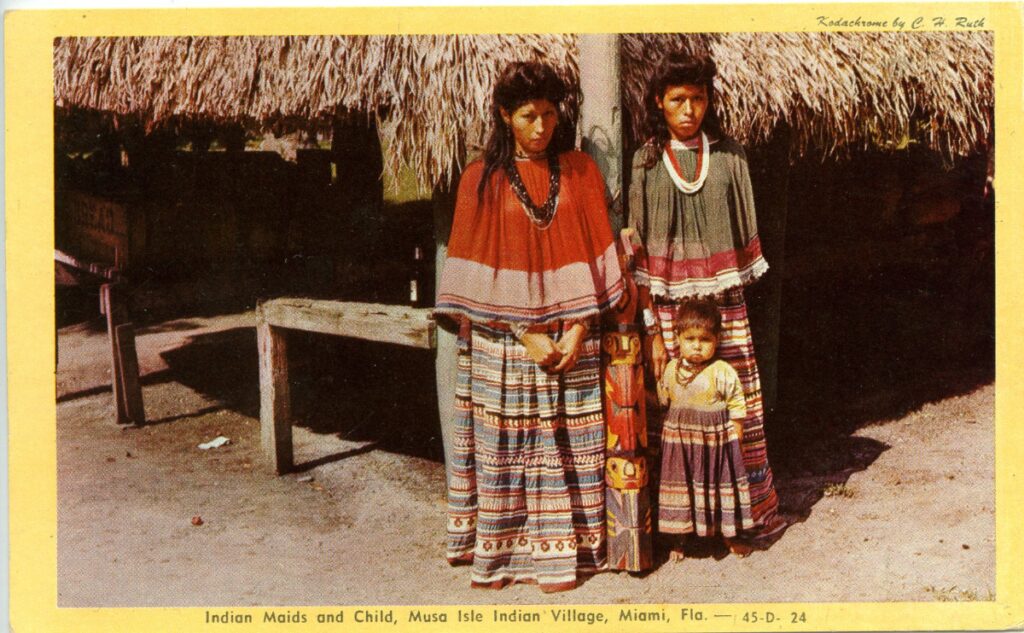

By the 1970s, Florida tourism was almost mythical in its allure; sandy beaches promising vacations of a lifetime. But, this boom was not exactly reflected in the Seminole experience of the 1960s. Due to a number of circumstances, Seminole tourism and economics struggled in this decade., necessitating economic resilience. Below, you can see Louise Doctor (left) and Alice Doctor (right) at Musa Isle in the 1960s. Note the small carved totem pole between them, next to Louise’s daughter.

2003.15.230, ATTK Museum

The Waning of an Era

For the Seminole Tribe of Florida, the 1960s represented a time of hopeful struggle and economic resilience. They had just received federal recognition in 1957, and were working hard to cement their agency as a sovereign nation. But, as much as Florida tourism was booming in the 1960s, Seminole tourism faced many challenges. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, construction on portions of Interstate 75 intended to support increased traffic around the Everglades. Interstate 75 opened in Florida in 1957, and continued through the 1980s. Alligator Alley opened on February 11, 1968. This 78-mile tolled road connects Naples/Fort Myers to Fort Lauderdale/Miami. Designed to support faster, more robust traffic, this four-lane highway cut across the Everglades. The use of the highway greatly reduced traffic along Tamiami Trail, and subsequently camps that depended on that traffic saw a decline in visitation.

The construction of more highways, interstates, and population-driven roadways had a noticeable effect on Seminole tourism, where “accessibility…was of paramount importance” (West 214). In Miami, ‘progress’ precipitated the closing of many historically impactful Seminole camps. For example, “the death knell tolled in the 1960s for the pioneer businesses of Musa Isle and Coppinger’s Pirate Cove (also known as Tropical Paradise), as Miami’s new expressway system sealed off access to those riverfront properties. Musa Isle closed in 1964 and Tropical Paradise in 1969” (West 227).

Despite these closures, other later attractions would pop-up, although not to the success seen by these early ventures. The original tourism entities became a point of pride and nostalgia, and “[the older generation] considered activities related to the tourist attractions to be a significant part of their cultural heritage” (West 228). Seminole tourism continues to be intimately connected with Seminole heritage today, and the marks of this early industry are a celebrated legacy.

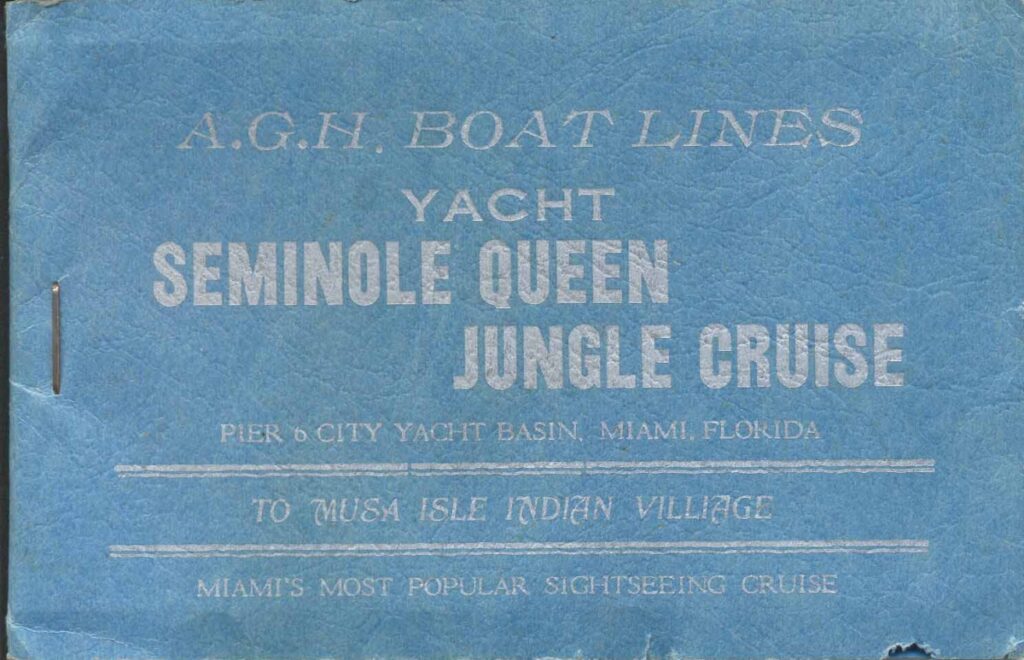

2001.66.18, ATTK Museum

Economic Resilience in a Changing World

But, despite these challenges, the Seminole people continued to display resilience and innovation in the face of struggle. Many camps, boat cruises, and alligator shows continued to run, despite barriers. Above, you can see a postcard book advertising the Seminole Queen Jungle Cruise in the 1960s, prior to Musa Isle closing.

Many prominent Seminoles worked at these tourist villages, including Betty Mae Jumper who we mentioned above. In fact, “in the 1950s and 60s Moses Jumper performed at the Jungle Queen Indian Village. When he could not perform, his wife, Betty Mae Jumper, a future Seminole tribal chairwoman, filled in as the only known Seminole woman alligator wrestler” (West 108). Families continued to support themselves through tourism, either at established attractions or road-side family camps. In many cases, “most families barely made ends meet” (West 253). Families from both the Seminole Tribe, the Miccosukee, and the Independent Seminoles continued to work and support themselves with the tourist dollar.

Tribal Businesses

On the business side, the Seminole Tribe of Florida continuously attempted to diversify and bolster their economic portfolio. Their first official business, the Okalee Indian Village, opened on the Hollywood Reservation in 1959. While it is an important historic and nostalgic location, Okalee would struggle on a shoe-string budget for decades and close multiple times. The Tribe also attempted to lease their land and bolster their image in big business. In a Miami Herald article from 1966, the author outlined the Seminole’s plans to construct an “industrial-tourism showplace” on the Hollywood Reservation (Miami Herald, 08 June 1966). The article noted that the “ambitious plan signals the entrance of the Seminoles into competitive economic society as the tribe seeks to diversify.” While large scale economic success would still be a decade away, these seeds of determination during a difficult period exemplify Seminole resilience.

Times are changing! Check back next month for our next installment in this Decades of Seminole Tourism series, which will explore the 1970s.

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting to Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.