Seminole Tourism Expansion in the 1920s

Welcome back to our Decades of Seminole tourism series! This week, join us as we navigate through the ups and downs of the 1920s to1930. In previous months, we have extensively covered the rise of Seminole tourism at the turn of the 20th century. To check out the beginning of our series, visit these previous blog posts about the 1900s-1910s and the 1910s-1920s. Also, there is an additional post about the rise of Seminole dolls in the 1910s-1920s. Now, we will focus on Seminole tourism expansion, with a look at how Seminole tourism flourished in the 1920s and became one of the biggest businesses in Florida.

Leaning into Tourism

This period of Seminole tourism builds on the foundations we have explored in previous posts. Seminoles would lean into tourism in a way that was unprecedented. Soon, tourist villages would expand and offer more to entice visitors. In Patsy West’s The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting To Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition the expansion of Seminole tourism and advertisement in the 20s is covered in detail. Soon, ads encouraging vacationers to come to Florida reached as far north as New York. West shares that “During the boom years of the 1920s, a large ‘electric’ sign in the heart of New York City on Broadway and 42nd Street glowed warmly in the cold of January, proclaiming, ‘It’s June in Miami’ (West 50-51).”

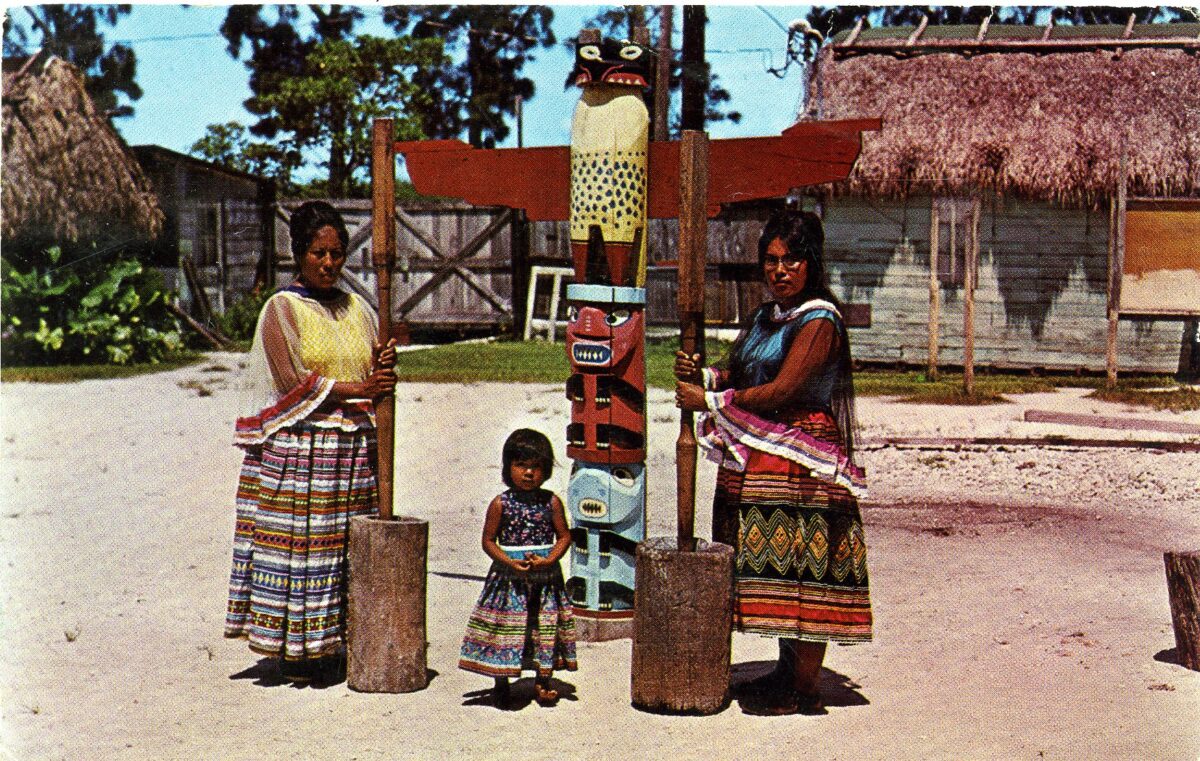

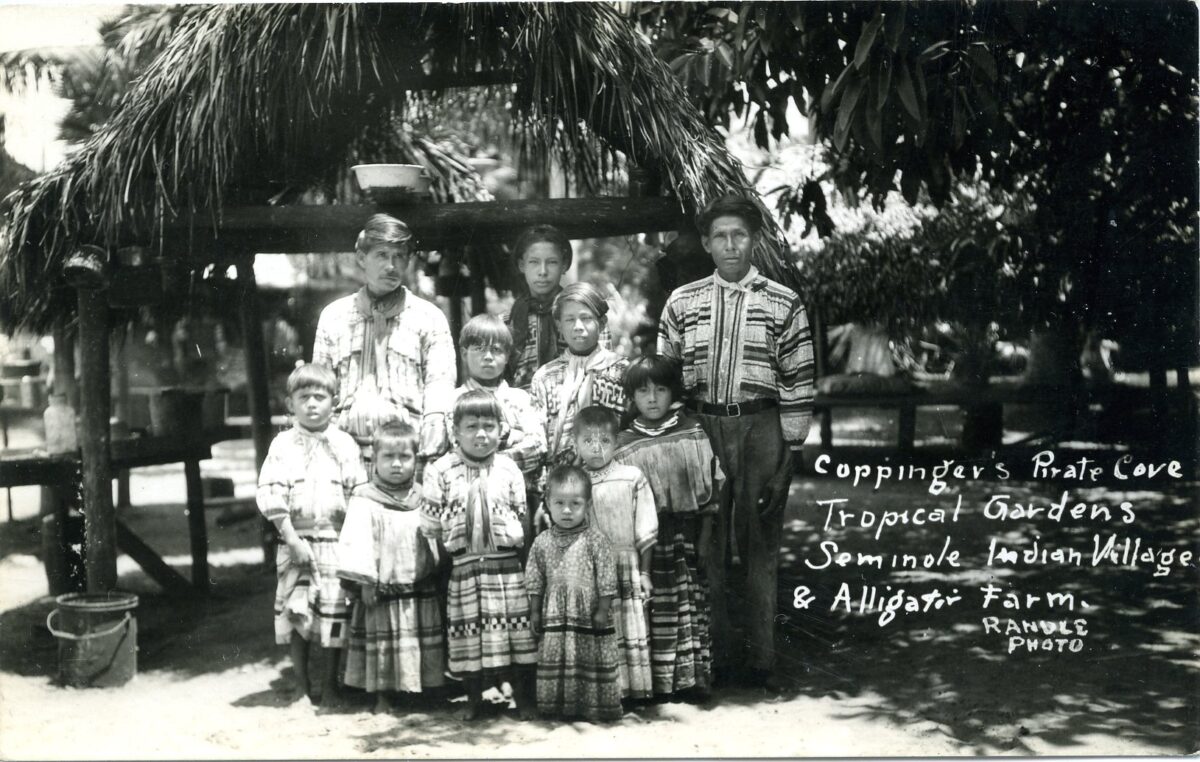

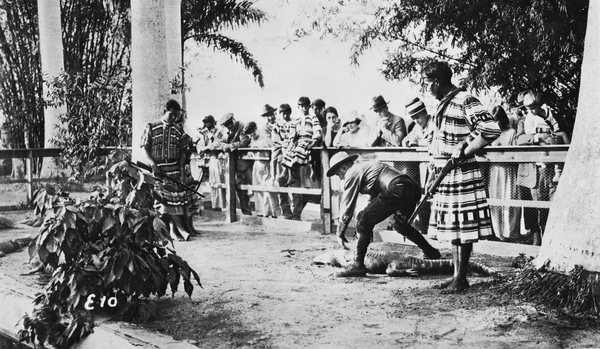

Ads across the east coast of the United States became increasingly popular. They would sell the sunshine, summer, and wonder of Florida. Seminoles were an important part of this. By the 1930s, Seminole villages had become the leading tourist businesses in the Sunshine State (West 57). Real photo postcards showing lush landscapes, Seminole alligator wrestlers, and village scenes made their way around the country. In Miami, Musa Isle Indian Village and Coppinger’s Pirate Cove competed for tourists with their Seminole villages. Only a little down the river, these two villages dominated Seminole tourism in the early 1920s. Throughout this article, we will highlight a few examples of this expansion, and how Seminole tourism became a powerhouse in Florida tourism.

Alligator Wrestling at Musa Isle, circa 1920s, Florida Memory Project

Musa Isle Seminole Village

Musa Isle Seminole Village on the Miami River hosted one of the most iconic Seminole villages during this tourist boom. It started as a tropical garden and citrus grove, much like Coppinger’s. Boats running up and down the river would stop for fruit, produce, and a glimpse of the Everglades. Musa Isle would quickly set up a Seminole village to bring in tourist dollars. A Seminole man, Willie Willie, leased a section of Musa Isle in 1919. Willie encouraged other Seminole families to camp there during the winter. They would sell crafts, cook, and do demonstrations for passing tourists. In 1922, Bert Lasher gained control of Musa Isle. Consequently, Willie Willie opened a different tourist attraction in Hialeah. Seminole families worked in Musa Isle for decades. It became an iconic tourist attraction in South Florida through the 1960s. Seminoles were an integral part of the success of Musa Isle.

Seminole Weddings

In the early 1920s, staged Seminole weddings became a popular trademark of South Florida tourist villages. Miami newspapers advertised the weddings to attract visitors and boost sales. Staged Seminole weddings began at Musa isle in 1923, under the direction of Bert Lasher. Lasher was the first to capitalize on Seminole weddings to bring in tourist dollars, but not the only. Below, you can see a black and white photograph from the wedding of “Cowboy” Bill and Annie Tiger at Musa Isle, circa 1932. Cory Osceola is directly identifiable to the right of the newlyweds.

Today, you can see many Real Photo postcards like this one depicting Seminole weddings at various villages. Often, newlyweds were already married. West states “There is no doubt that some of the couples participating in the wedding extravaganzas were already married, even with children, when their vows were witness as tourist attractions (West 62).” Thousands of tourists came to see these heavily advertised Seminole weddings.

2003.15.56, ATTK Museum

The first Seminole wedding at Musa Isle featured Cory Osceola and Juanita Cypress (West 55). Cory Osceola was the head man at Musa Isle at the time, and we have featured him in previous blog posts. In 1985, their son O.B translated for his mother in an interview, sharing “Yeah [they had] a celebration for them. When they do that, they advertised a lot and they get a lot of people in the village, a lot of excitement. At the same time, they make a lot of money too. That’s part of the game(West 61).” These exciting, special events brought in big tourist dollars. Coppinger’s soon began hosting their own Seminole weddings, to compete with Musa Isle.

Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens

Just down the river from Musa Isle, Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens, eventually Coppinger’s Pirate Cove, formally opened in 1917. We touched a bit on Coppinger’s in a previous blog post. Within a year of opening, unusually low temperatures destroyed the succulent tropical garden (West 47). Coppinger’s would establish their first Seminole Village soon after. Coppinger’s was famous for popularizing alligator wrestling for tourists. Alligator wrestling would soon become associated with Seminoles, even though Coppinger first pushed the practice. But, Seminoles were no strangers to taming alligators. Hunting alligators in the Everglades was an important part of Seminole survival. But, this new, stylized wrestling pushed those skills to the next level. Musa Isle would soon follow with their own gator farm and wrestling shows, as would many other camps. Alligator wrestling is still important to Seminole culture and tourism.

In our featured photo this week, we can see two men and nine children posing in front of a chickee. They all wear patchwork. The handwritten caption notes the photo was taken at Coppinger’s Pirate Cove Tropical Gardens Seminole Indian Village and Alligator Farm. This Real Photo postcard would have been sold to tourists.

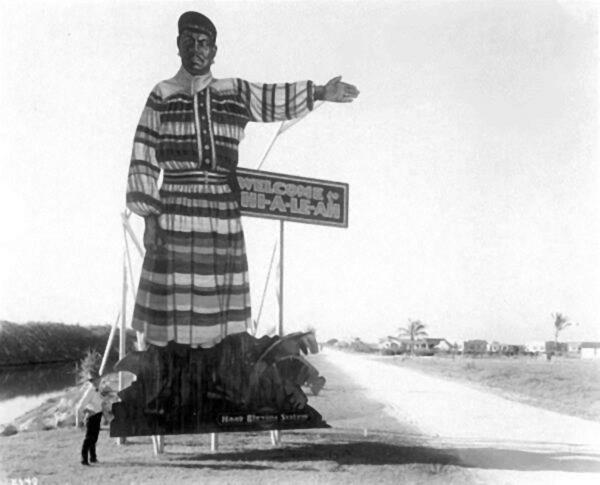

Pointing Man Signs

Around this time, the famous Pointing Man signs began to make their impact. Jack Tigertail, born in the Big Cypress swamp, was the inspiration for these famous signs. By 1918, Tigertail and his family lived at Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens for the tourist season (West 48). Tigertail was a well-liked and popular figure in Miami, and the headman at Coppinger’s. His ability to speak English allowed him to jump the gap between cultures. The first Pointing Man sign was erected in the new town of Hialeah. It is located northwest of Miami. Hi-a-le-ah means “high” or “pretty prairie” for Mikasuki-speaking Seminoles (West 58). In 1921, cattleman James Bright and investor Glenn Curtis converted Bright’s Hi-a-le-ah cattle ranch into prime real estate. Bright had bought the land in 1914 to graze his cattle. Before, the location was a meeting point for Seminoles and Miccosukee, as they canoed along the Miami River.

Jack Tigertail’s likeness was used to construct a 25-foot tall wooden cutout directing motorists to the new town of Hialeah. Dressed in a traditional Seminole bigshirt, Tigertail’s outstretched arm was literally larger than life. From as far away as Jacksonville, huge billboards showing Tigertail would point their way to the burgeoning city (West 57). The image even made its way on to the town logo. Eventually, the image of the Pointing Man became an icon in Seminole tourism. Other roadside cutouts were constructed, pointing to various Seminole and Miccosukee tourist stops. Today, the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum even features Pointing Man signs along their boardwalk, to honor the tradition.

Perseverance

But, the economic boom seen in the Seminole tourist villages of the early 1920s would soon be in jeopardy. In September 1926, a massive hurricane hit South Florida. A Category 4 cyclone, it devastated the greater Miami Area. Both Coppinger’s and Musa Isle were heavily damaged, and Willie Willie’s Hialeah tourist attraction was entirely destroyed (West 63). Musa Isle repaired quickly. But, Coppinger’s was closed for over two years. The storm also ended the real estate boom of the 1920s for South Florida, and foreshadowed the economic decline of the Great Depression. While the tourism boom of the 1920s had long lasting effects, the crash significantly impacted the economics of Seminoles into the 1930s.

Despite these trials, “by 1930, well over half the [Mikasuki speaking Seminole] population, even those in isolated Big Cypress and in Collier County, had become involved in tourist attraction employment, while virtually all of the population was engaged in supplying the goods to this novel market (West 38).” The rise, popularity, and tenacity of Seminole villages like these is testament to Seminole resilience. Outside of the Miami villages, Seminoles also began to travel more within the state to different events and diversify their crafts. Consequently, the Seminole tourist economy was well established throughout Florida by the end of this decade. The triumphs of the 1920s would set the Seminole people up as vital parts of the Florida tourist economy for decades.

West’s book was accessed digitally while researching this article. So, page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting To Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.