Seminole Economic Independence in the 1940s

Welcome back to our Decades of Seminole Tourism series! Over the last few months, we have explored Seminole resilience in tourism, and how the Seminole people have persevered through unimaginable hardship. Last month, we looked at Seminole Exhibition shows in the 1930s. As we transitioned through the 1940s, Seminole tourism and economic independence would explode in an unprecedented way. In many ways, the 1940s took building blocks from the previous four decades and built the foundation for the Seminole Tribe of Florida we know today. So, this week join us as we look at this pivotal decade!

In our featured image for this week, you can see a group of Seminole children standing in front of a car at the Brighton Indian Day School in the 1940s (2002.10.6, ATTK Museum). Seminole life, tourism, and economic independence experienced many on and off reservation changes throughout this decade, which would set the scene for the modern Seminole Tribe of Florida.

Turmoil and Growth

The events of the 1940s would completely transform Florida and Seminole tourism. Although we have been discussing Seminole tourism from 1900 onward, tourism in Florida didn’t explode into the powerhouse sector it is today until after WWII. The United States heavily depended on the people and resources of Florida. Agriculture, ship-building, and the military became big business. More than 250,000 Floridians were drafted or enlisted voluntarily, and due to the climate and location, dozens of military bases were constructed or enlarged. Personnel to support these enterprises flooded the state.

This massive influx of people would buoy the state’s economy. They would spark the tourism boom post-war Florida would ride for decades. This population growth would continue after the war ended, and “many soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen and nurses who trained or served in Florida later returned to the state as visitors or new residents.” After WWII, Florida had the infrastructure and economic means to accommodate this rapid growth in the tourist industry.

During this decade, Seminoles moved predominantly between family camps on Tamiami Trail and the reservations. One reason was to avoid government notice, and “camps on Tamiami Trail were enlarged to accommodate families who fled the reservation [to avoid the draft]” (West 191). While it may seem like they were merely avoiding the war, the reality is a tad more complex. Seminoles were still uncertain and distrustful of the government, and “they refused to register for the draft, not so much because they would not fight for the land, but because they adamantly opposed signing their names or making their marks on the forms” (West 190). However, there was one that served. Below, you can see a photo of Howard Tiger, who was the only Seminole to serve in WWII. It is with this context in the background that we can examine the growth of the 1940s, and the Seminole experience during this decade.

2002.166.481, ATTK Museum

On Tamiami Trail

Camps on Tamiami Trail continued to be important economic ventures for Seminoles through the 1940s. Along the trail, Seminoles would sell arts and crafts, wrestle alligators, pick crops, and even start a lucrative frog meat trade that spawned the invention of airboats (West 191). It was also at this point that Seminoles began to break from white-owned ventures like Musa Isle and Coppinger’s in favor of their own enterprises. In essence, “these camps…are important: they mark an increased economic independence for these Native Americans separate from the white-operated attractions in the city” (West 178). They represented not only economic independence, but also a chance to maintain their lifestyle and freedom. By 1936, the camps on Tamiami Trail would include camps headed by Robert Billie, Ingram Billie, Josie Billie, Johnny Osceola, Corey Osceola, Chestnut Billie, John Motlow, and William Mckinley Osceola (West 180). But, these endeavors did not come without barriers.

Around this time, vocal opponents of Seminole attractions began to appear under the banner of altruism. Deaconess Bedell, an Episcopal deaconess and missionary, was the most prominent. Bedell felt “the attractions were a barrier on the road to more appropriate economic opportunities” (West 206). Instead of the camps, Bedell encouraged the marketing and sale of what she deemed “authentic” Seminole crafts. The Glades Cross Mission, which Bedell operated in Everglades City, bought and sold Seminole crafts– but only those patchwork patterns, doll styles, and crafts Bedell considered authentically Seminole. Similarly, the U.S. government discouraged the Seminole attraction economy, trying to manipulate Seminole endeavors to those they deemed acceptable. Their “idealistic plans for these Native Americans were in direct opposition to the job descriptions at the attractions, and…Seminole will” (West 211). While Seminoles did benefit from these programs, the attraction economy that helped them grasp economic independence was unfairly sabotaged.

The Seminole Reservations

After the land boom of the 20s and 30s, it became increasingly hard for Seminoles to live, hunt, and support themselves by traditional means. Concerned Tribal leaders, working with the Friends of the Seminole, petitioned for land to be brought into trust for the tribe. This was granted in 1938, when some-80,000 acres were designated across three reservations. The Brighton reservation, located northwest of Lake Okeechobee, held about 36,000 acres. Big Cypress in Hendry County, where the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum is now located, encompassed 42,000 acres. The Dania Reservation, now the Hollywood Reservation, had around 460 acres (The Miami Herald, 13 Jan 1946, p 27). Few Seminoles lived on the reservations in the 20s and 30s. Unsurprisingly, Seminoles were wary of the U.S. government and resisted. But, federal programs aimed at improving economic opportunities on reservation would change this going into the 1940s.

Soon, cattle programs, health, education, land improvement, and crafts programs would be established on all three reservation plots. Actually, “the first craft program for reservation Seminoles began in 1940 [on the Brighton reservation]. With aid from the fledgling Indian Arts and Crafts board in Washington, Edith M. Boehmer organized the Seminole Craft Guild” (West 126). These programs would prove to be beneficial, vital parts of Seminole economics. But, it is important to note that Seminole tourism through attractions would persist despite the barriers discussed above. The ways in which Seminoles were proving their ability to operate independently of the government were deemed “unacceptable” merely because they were not controllable. The U.S. government and outside entities continued to attempt to limit and control Seminole economic ventures, discouraging the attraction economy to a degree that it limited Seminole agency.

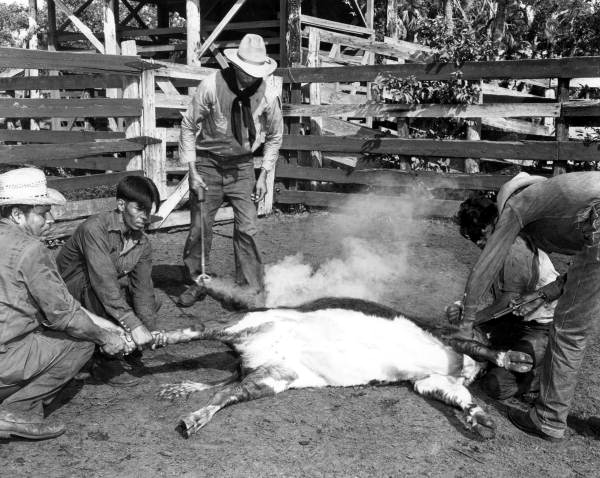

Seminole Indian cowboys marking and branding a calf in the corral during round-up – Brighton Reservation, Florida. 1950. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

Cattle

Seminoles have a long history of working cattle. There is little doubt that they have been involved with the Florida cattle industry for centuries. But, war, rustling, and unrest would plague Seminole cattle endeavors from Spanish contact through the Seminole War period. Despite this, there were periods of significant Seminole involvement in the Florida cattle scene. Around the mid-1700s, followers of the Oconee leader Cowkeeper would settle outside of Alachua. By 1775, there were historic records of Seminoles working up to 10,000 head of cattle on Payne’s Prairie outside Gainesville. Continued aggressions would depress the following centuries between Seminoles and European-American settlers. Up through the Seminole War period and the Civil War, cattle ranching was a liability, despite Seminoles being excellent cattlemen. But, modern Seminole cattle programs gained more traction in the 1930s.

Although it would begin in the mid-1930s when the Dania and Brighton Reservation acquired starter herds, this new era of Seminole cattle ranching would find its legs in the 1940s. The Seminole Tribe founded the Indian Livestock Association at the end of the 1930s. In 1944, they established separate enterprises for Big Cypress and Brighton, overseen by the Central Tribal Cattle Organization. By 1946, there were “2,700 head of sleek stock grazing on the Brighton agency range and more than 800 at Big Cypress” (The Miami Herald, 13 Jan 1946, p 27). In just a few years, they were operating in the red. The News-Press out of Fort Myers reported that the Big Cypress and Brighton cattle enterprises declared a profit of $7,000 in 1948 (News-Press, 6 Jan 1949, p. 1). These two enterprises would steadily grow, resulting in the Seminole Tribe being one of the leading beef producers today.

Rodeos

In tandem with the continued growth in the Seminole cattle industry, Seminole rodeos begins to appear in historic newspapers. Soon, rodeos and cattle drives would become an important facet of Seminole culture and history. One such rodeo is held during Brighton Field Day near Okeechobee, FL. In addition to a rodeo, the event will include Seminole food, crafts, art, and live music. Interested in attending? The Seminole Tribe of Florida will host Brighton Field Day 2023 on February 17-19, 2023 at the Fred Smith Rodeo Arena on the Brighton Reservation.

Chalo Nitka

First held in 1948, the Chalo Nitka Festival started to celebrate the paving of Main Street in Moore Haven, FL. The name means “big bass,” a Seminole term first translated by Lonnie Buck. Seminoles are very involved in the festival. Many events “showcase the southern hospitality of Glades County and our friends from the Seminole Tribe of Florida.” The first festival featured a week-long fishing derby for residents around Lake Okeechobee, a concert, dance, and free barbecue with swamp cabbage. Anyone who catches a bass during the derby entered the Royal Order of the Bass. The winner of the largest bass was then crowned King or Queen of the Bass. Below, a girl is crowned Queen of the Bass in 1950. Josie Billie is standing behind her.

2009.34.1534, ATTK Museum

Moore Haven still holds Chalo Nitka today, and is one of the oldest continuously running festivals in Florida. Since it began, the festival has evolved into a week-long series of events featuring alligator and livestock shows, a rodeo, parade, and more! Moore Haven will host the main event March 4, 2023 at Chalo Nitka Park. Admission is $5 per person, with children under 5 free. Admission is also free for anyone wearing a same-year Chalo Nitka t-shirt or traditional Seminole attire.

Seminole Economic Independence

The 1940s were a time of turmoil. But, they were also one of continued economic independence and growth for Seminoles and Seminole tourism. Although this did not spell the end of economic hardships by any means, the 1940s established a foundation on which Seminoles could grasp economic independence on their own terms. The gains of this decade would pave the way for the Seminole Tribe of Florida to form in the 1950s. Check back in with us next month to learn more about how the Seminole Tribe of Florida gained federal recognition and pushed Seminole tourism to the next level. Don’t forget to check out previous blog posts on the 1900s, 1910s Part 1, 1910s Part 2, 1920s, and 1930s.

Sources:

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting To Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.