1910s-1920s: Tourist Attractions Show Seminole Resilience

Welcome back to our series on Decades of Seminole Tourism! In this two-part installment, we will explore the period between 1910 and 1920. This was a time of great change for Seminole people, and Seminole tourism. Before Disney, Seminole villages were a true tourist attraction. In the 1910s through 1920, these tourist attractions became increasingly popular, and represented Seminole resilience in a changing world. This week, we will look at this next wave of tourist attractions and exhibition shows. Next week, check back in for a deeper dive into Seminole dolls. Hot commodities in tourist camps, these dolls are unique reflections of Seminole identity and culture.

A Changing Florida

In the first installment of this series, we talked about Tom Tiger’s Camp. The first example of Seminole tourism, Tiger’s camp opened in 1904. This camp would set the stage for the next 100 years of Seminole tourism. In the following decades, more Seminole tourist attractions, camps, and exhibition shows would open in South Florida. Musa Isle Trading Post and Seminole Indian Village, Coppinger’s Tropical Garden, and eventually family camps along Tamiami Trail became staple South Florida tourist attractions. While they may seem like simple endeavors, they became much more than that. These tourist attractions were another example of enduring Seminole resilience in the face of a changing world. While Tom Tiger’s camp was first, more expansive attractions would begin to open between 1910 and 1920. Throughout this post, we will outline the changes that happened during this period, and how it cemented Seminole tourism for a century to come.

Tamiami Trail cut across the Everglades, and officially opened in 1928. With it came many changes in the ecological and cultural landscape of Florida. But, even before surveying began in 1919, things were shifting for Florida and its tourism. After the Civil War, railroads began to link parts of Florida. In a previous blog post about early Florida transportation, we talked about Plant and Flagler’s railroads through the swamp. This, along with steamboats chugging along larger inland rivers, would revolutionize the economy of Florida and draw more and more settlers to the rugged swampland. With these settlers came development projects, and the drainage of the Everglades. It spelled the end of the trading post era, and with it the fragmentation of the Everglades. Seminole people could no longer stay disconnected, and were forced to adjust to survive. In another example of Seminole resilience, camps and tourist attractions soon became popular.

Rise of Tourist Camps and Festival Demonstrations

While we often first think of family camps on Tamiami Trail as the earliest examples of Seminole tourism, the reality is a bit different. In the early 1910s through the 1920s, Tamiami Trail had still not linked South Florida. Thus, despite railroads making travel easier, most settlers did not stray far from the coasts. If you recall, Tom Tiger’s camp found its place in Miami. Eventually, tourist attractions along the rivers in Fort Lauderdale and Miami would boast Seminole Indian Villages. Much like Tiger’s camp, canoe demonstrations and boat rides would entice tourists to take a peek at Seminole life. But how did they develop? After Tiger’s camp, the next few to be established were seen in the late 1910s in Miami. Many of these would run for decades. While the Seminoles didn’t own them, they often gave them a lot of financial opportunity when they really needed it.

Canoe trails and hunting grounds were decimated by the changes in the Everglades. Trading posts had become a thing of the past, and these tourist attractions were a boon in a desperate time. They also paved the way for greater financial opportunities down the road. According to Patsy West, author of The Enduring Seminoles “Most of the families who set up these earliest Seminole owned and operated tourist attraction businesses were first- and second-generation employees of the popular Miami tourist attractions Coppinger’s Tropical Garden and Musa Isle.” (Patty West, Reflections, Number 176) Once the chance presented itself, many struck out on their own. But, the bouncing off point started at those big-name attractions.

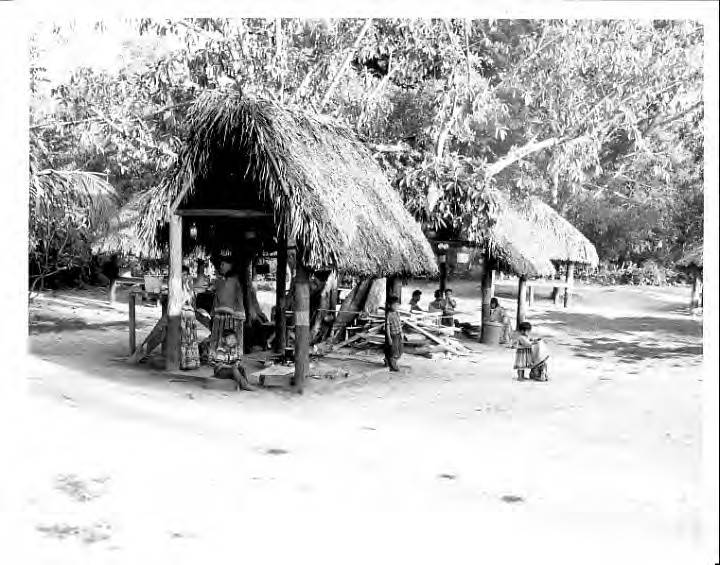

Seminole Indian village reconstruction at Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens: Miami, Fla. 1948.

Courtesy, Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System.

Musa Isle and Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens

Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens would open in 1918. Musa Isle, the other popular tourist attraction on the Miami River, would open around the same time. Both locations started as tropical gardens and citrus groves. Just down river from each other, they both would run for decades. Boats going up and down the river would stop for juice and produce. Both would quickly open Seminole villages. Seminole people were hired to live and work in the villages. They would make crafts, cook, and do demonstrations for visiting tourists. Heavily advertised, they were popular with both locals and visiting tourists. Of the two, Musa Isle is the most remembered, and flashy ads from the 1930s and 1940s are still easy to find today.

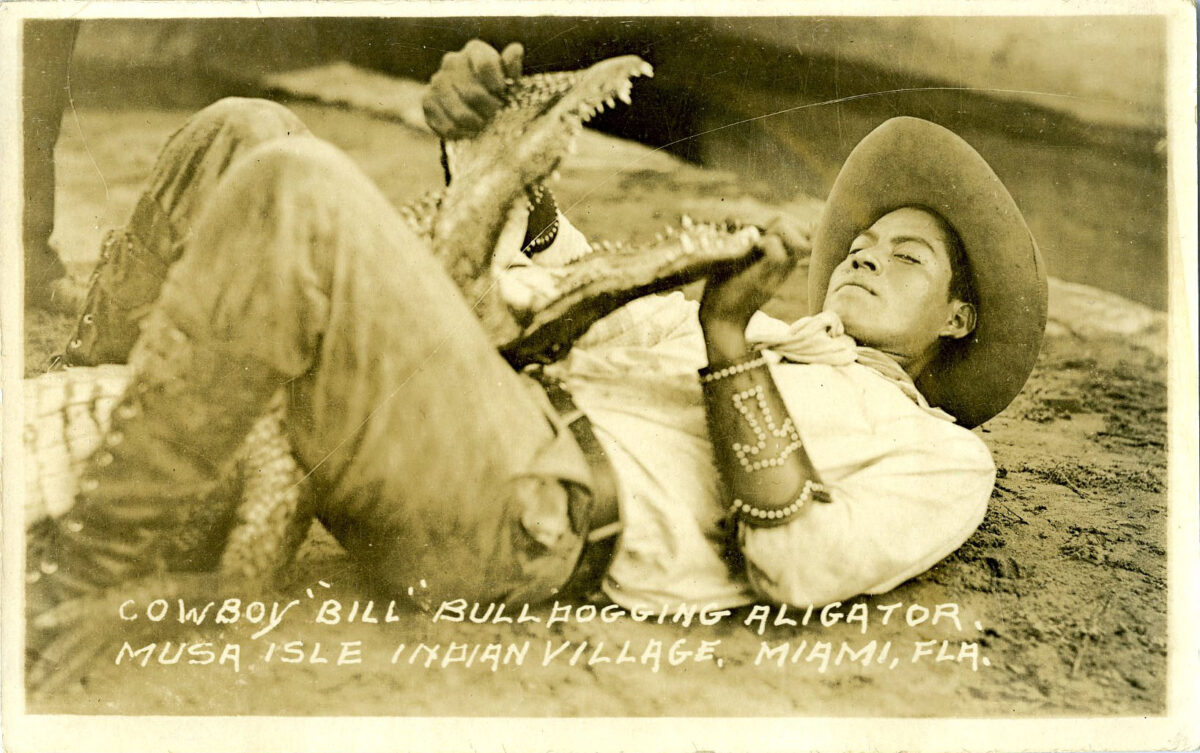

In the featured photo for this week, we can see Cowboy Bill holding an alligator’s jaw open at Musa Isle Indian Village in the 1930s. For more information on Musa Isle, follow this series as we explore the following decades.

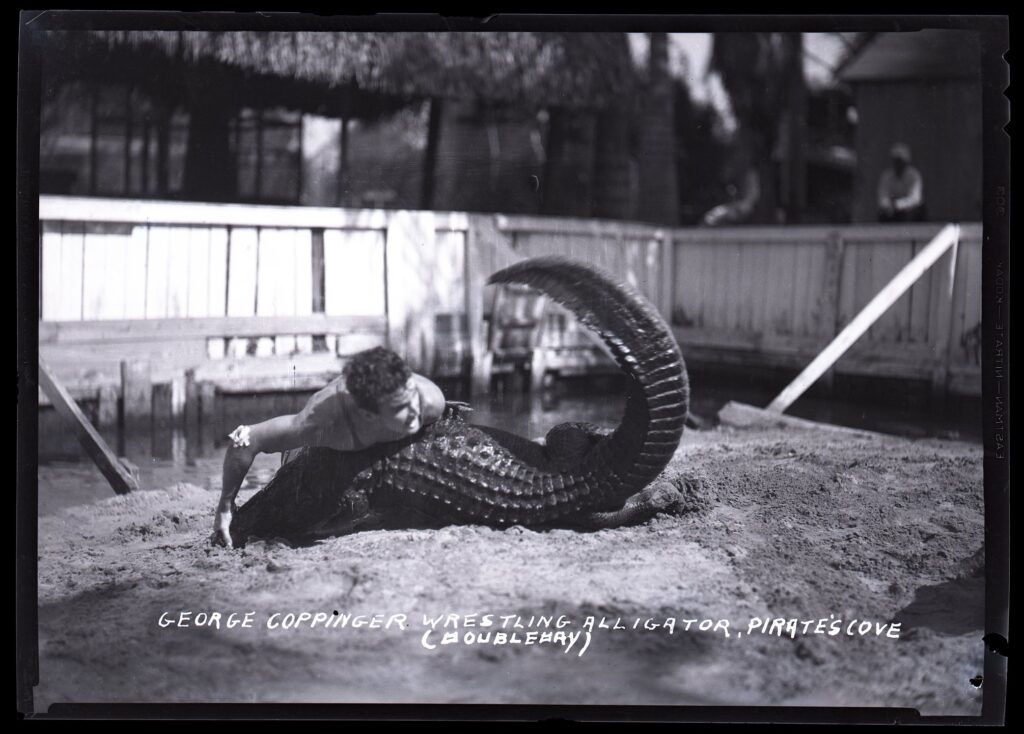

Alligator Wrestling

Alligator wrestling as a tourist attraction was put on the map at Coppinger’s Tropical Garden in the early 20th century. Below, you can see George H. Coppinger wrestling an alligator at Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens in Miami. Also known as “Alligator Boy”, his brother Henry Coppinger Jr. was the first to trade on alligator wrestling and gator farms as a tourist attraction. Musa Isle would soon follow, as would many other camps. While these white-owned villages were the first to capitalize on alligator wrestling for tourism, Seminoles were no stranger to handling alligators. Hunting alligators in the Florida Everglades was an important part of their survival. Now, though, they wrestled them out of necessity for tourist dollars. The heart stopping action would fuel Seminole tourism for years to come. Even today, alligator wrestling is an integral part of the Seminole story and a cherished activity.

While it may look violent, Seminole alligator wrestling is not only a cultural touchstone. In a New Yorker article from 2021, modern alligator wrestler Everett Osceola described wrestling as more about “educating people” than anything else. Wrestlers develop relationships with the alligators they work with, building a synergy felt by both parties. As development took over swampland, alligators even became endangered in the 1960s. In the article, Osceola notes that “They helped us survive, and then, at a certain point, we helped them survive.” Now, modern Seminole wrestlers work to educate people about not only Seminole history, but also what it means to respect and live among alligators. After wrestling for a while, many are released back into the swamp.

George Coppinger and Fighting Alligator. Doubleday. 2013.3.228. ATTK Museum

Patchwork, Crafts, and Seminole Dolls

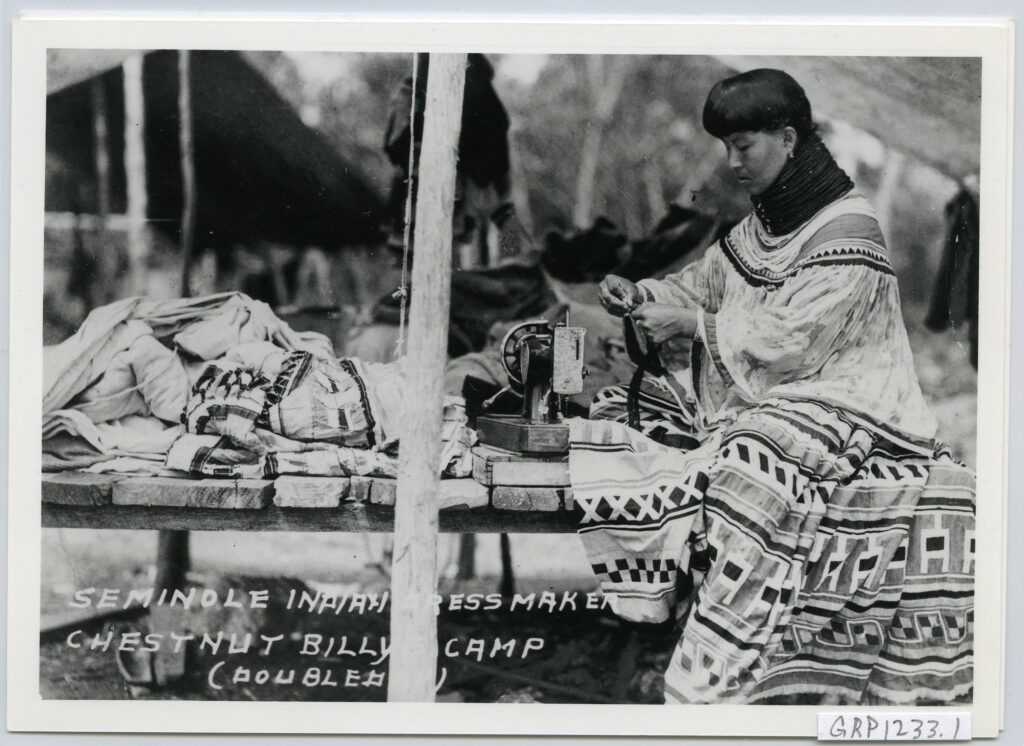

At the same time Seminole tourist attractions were making their mark on South Florida, so were Seminole crafts. To bring in income, Seminole crafters would sell crafts to tourists. Along with exciting exhibits, tourists could bring home a piece of Seminole culture. Intricate patchwork appeared around the 1910s. Although we do not know exactly when patchwork began to be made, it is documented in photographs for the first time around World War 1. The late 19th century saw the introduction of hand crank sewing machines. These allowed Seminole and Miccosukee women to create patchwork with ease, and helped them become a popular tourist craft. Patchwork is made using geometric patterns on strips of fabric. Some patterns represent important stories and legends, and others may be personal. The intricate designs also showcase Seminole crafting skill on Seminole dolls.

Dolls, wood carvings, baskets, and other crafts would eventually make their way into tourist attractions. Tourists took home miniature carved canoes. Real photo post card books were also popular souvenirs. You can learn more in a previous blog post about the Power of Postcards. Around 1918, palmetto husk dolls would be added to the craft offerings. Stylized features and hair resembling traditional Seminole styles, with patchwork clothing, would set the dolls apart. To learn more about Seminole dolls, check back in next Friday for a post dedicated to them. We will explore the history of Seminole dolls, how they are made, and how they represent Seminole identity and culture. To learn more about Seminole sweetgrass baskets, visit previous blog posts here and here.

June Mathers sewing patchwork at Chestnut Billy’s Camp, GRP1233.1, ATTK Museum

A Transformative Time

These early decades of the 20th century would set the Seminoles on a path that would continue even today. The period between 1910 and 1920 was one of struggle, and it would be dishonest to say that struggle ended quickly. Even with the economic opportunities seen in tourism, they were often dependent on the whims of non-Seminole Floridians and tourists. But, the evidence seen from these camps and tourist attractions was clear. As we move through the rest of this series, it is important to recognize these threads of resilience and dedication to home and culture.

Author has corrected genealogical details present in a previous publishing of this article.

Pingback: 1910s-1920s: Seminole Dolls - Florida Seminole Tourism