Federal Recognition in the 1950s

Welcome back to our series on Decades of Seminole Tourism! It has been a few months since our last post in this series, and we are coming back talking about one of the most transformational eras in Seminole history. The Seminole Tribe of Florida gained federal recognition from the United States in 1957. This would allow the Seminole Tribe of Florida to coalesce into the established, sovereign nation we know today. Join us to explore the 1950s, and how the federal recognition of the Seminole Tribe of Florida would shape Seminole agency and power from then on. In turn, it would place power over Seminole tourism directly back in the hands of the Seminole Tribe.

2009.34.387, ATTK Museum

Above, Little Fewell, Jackie Willie, Bill Osceola, and an unidentified boy sit on the back of a flatbed pickup truck in a cattle pasture. Big Cypress Seminole Indian Reservation, May 1957. Cattle were well-established as an important economic venture on the reservations through this period. In a February 1, 1950 News-Press article, Seminoles were quoted to have over 5,000 head of cattle, and over half a million dollars in cattle and equipment. By this point, individual farmers outside the Tribal Cooperative started their own private herds. Seminoles have been tied to Florida cattle for hundreds of years. Today, cattle remain a significant part of the Seminole story.

In our featured image, Brighton Cattlemen of the recently organized cattle program display their brands in the late 1940s. In just a decade, these men would establish a cattle program that would put Seminole cattle as powerful economic contenders. Left to right are Willie Gopher, Joe Henry Tiger, Jack Smith, Frank Huff, Andrew Jackson Bowers, John Josh, Naha Tiger, Toby Johns, Frank Shore, John Henry Gopher, Lonnie Buck, Charlie Micco and Harjo Osceola.

The Council Oak and Indian Termination

From about the mid-1950s through the 1960s, the US government enacted a number of policies and laws, which we now refer to as Indian Termination. The U.S. government sought to terminate the trustee relationship they held with the tribes, to assimilate them entirely as ‘Americans’. On the face of it, it seemed altruistic, appearing that “Congress wished to liberate tribes from federal control.” But, the reality was much more insidious, and these policies in practice were another avenue to control and erase indigenous rights, culture, and ways of life. These policies ended the government’s recognition of tribal sovereignty. On assimilation, former US Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell (Northern Cheyenne) stated the driving perspective was: “If you can’t change them, absorb them until they simply disappear into mainstream culture” (American Indian Nations 3). The threat to indigenous life, culture, and sovereignty was powerful.

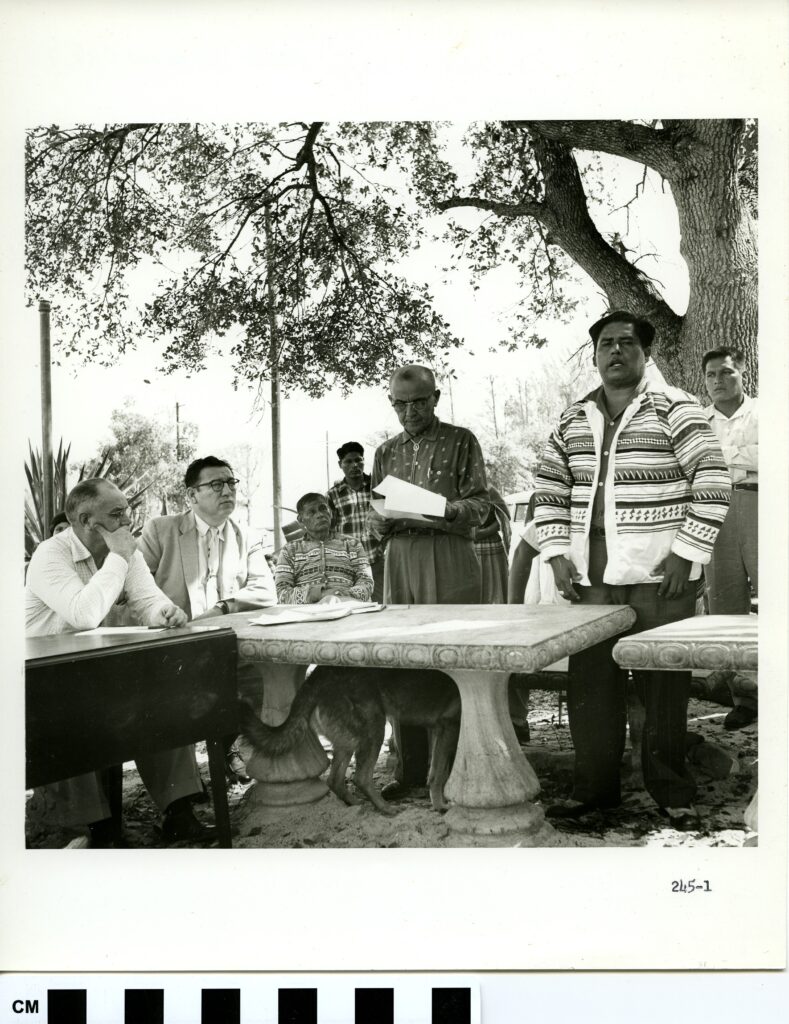

In response, a “new generation of Seminole leaders began to meet regularly under the branches of an old oak tree on the Hollywood reservation during the 1950s.” They sought to discuss these Indian termination policies, and work to a solution that preserved Seminole culture and sovereignty. Under the Council Oak, these leaders decided to form a tribal government, and cement that sovereignty. Below, you can see a black and white photo from a March 1957 Constitution and Charter Committee meeting on the Dania Reservation. From left to right, you can see an unidentified man, Res (Rex) Quinn, Josie Billie, Joe Bowers (background), U.S. Indian Agent Kenneth A. Marmon, Billy Osceola, and Jack Willie. The Council Oak still stands today on the Hollywood Reservation, a symbol of this pivotal moment in Seminole history.

2009.34.5083, ATTK Museum

All of Florida is Seminole

Seminoles developed a formal constitution and corporate charter under the Council Oak, establishing a two-tiered government. It is composed of a Tribal Council and Board of Directors, with elected representatives from each reservation community. On August 21, 1957, the Seminole people would vote on the ratification of this constitution and corporate charter, and start down the path to recognition (Tampa Tribune, 17 July 1957).

The U.S. Congress officially recognized the Seminole Tribe of Florida as a sovereign nation that same year. Later in 1970, the Indian Claims Commission would collectively award the Seminole Tribe of Florida and Seminole Nation of Oklahoma “$12,347,500 for the land taken from them.” But, this path forward was fraught. Increasingly, cracks between the more traditionally leaning Miccosukee and those aligned under the Seminole Tribe of Florida became apparent. Most Seminoles would align under the Seminole Tribe of Florida, but not all.

In 1954, Miccosukee elders hand delivered the Buckskin Declaration to President Eisenhower. It reads “we are not White Men but Indians, do not wish to become White Men but wish to remain Indians, and have an outlook on all of these things different from the outlook of the White Man.” Wholeheartedly, they had no desire to become part of the American system. Instead of financial compensation, the Miccosukee expressed fears that more of their ancestral homelands in the Everglades would be swallowed in the name of ‘progress’. In doing so, they claimed “All of Florida” as Seminole (Miami Daily News, 30 Dec 1955). The resulting legal battles would politically split the Miccosukee and Seminole Tribe of Florida. The United States federally recognized the Miccosukee Tribe separately in 1962. A small few who chose not to align with either tribe exist today as ‘Independent’ Seminoles.

On Tamiami…

Into the 1950s, life on Tamiami Trail continued to support many Seminole families. Many family camps, as well as places like Musa Isle, continued to operate within this era. Families would travel from their homes on the reservations to work at tourist camps, selling crafts like patchwork, dolls, and baskets. Seminole men supported a robust frog gigging trade, developing airboats to skip over shallow swampland. To learn more about life on Tamiami Trail leading up to, and through, the 1950s, check out previous blog posts on the 1900s, 1910s Part 1, 1910s Part 2, 1920s, 1930s, and the 1940s.

…and Beyond the Trail

Around this same time, Seminole culture and history began to make social impacts in the wider Florida consciousness. Through two specific artistic examples, we can see threads of Seminole resistance in the face of these termination policies, which would attempt to eradicate Seminole culture and in turn, the Seminole people.

In 1954, a play depicting Osceola’s life story ran in Hollywood, FL. With a nearly all-Indigenous cast, The Life of Osceola “was rehearsed only once [and] was produced against tremendous odds” (Fort Lauderdale News, 23 Jan 1954). Laura Mae Osceola wrote The Life of Osceola, and the performers were paid by audience donation. Laura Mae even stated before the play began that “If you don’t think the play was any good, you all don’t have to give us anything” (Fort Lauderdale News, 23 Jan 1954). Yet, it made a marked impact on audiences, who for one performance even waited over half an hour as the truck bringing the performers broke down on the way.

In 1958, Wind Across the Everglades would release in theaters. Loosely based on the life, and eventual death, of game warden Guy Bradley, Wind Across the Everglades also starred prominent Seminole leader Cory Osceola and his daughter Mary Moore Osceola. We have mentioned Cory Osceola before as a businessman, leader, and activist, as well as his connection to Musa Isle. Read more about Mary Osceola Moore here, written by niece Tina Osceola. This film has been previously featured by the Native Reel Cinema Festival. Check back in for updates on this year’s Festival at the 2023 Seminole Tribal Fair & Pow Wow.

Budd Schulberg, left, shaking hands with Cory Osceola during the filming of the movie “Wind Across the Everglades”. Florida Memory Project

Agency as a Sovereign Nation

This upheaval, political and economic, occurred concurrently with the strides seen in Seminole tourism. Whether it was through family tourist camps or early representation in film and plays, Seminole tourism began to shift and grow along with this solidified political agency. As we touched on in a previous post, Okalee Indian Village was the first official enterprise of the newly minted, federally recognized, Seminole Tribe of Florida. Built in the late 1950s, Okalee Indian Village represents the first, official moment of Seminoles cementing their own agency. Several public figures, like Deaconess Bedell, vocally opposed Seminole attractions and exhibition culture, deeming them ‘inappropriate’. Similarly, the U.S. government’s “idealistic plans for [Seminoles] were in direct opposition to the job descriptions at the attractions, and…Seminole will” (West 211).

Opening Okalee as a classic representation of a Seminole tourist attraction leaned into tourism, in direct defiance of this opposition. Wrestling back power from the federal government, Okalee placed Seminole success as the main priority of the Tribe. Similarly, Seminole authors like Laura Mae Osceola putting on a Seminole play filled with Seminole actors, and Cory Osceola being shown on the silver screen, were further acts of defiance. In the face of Indian termination, which Ben Nighthorse Campbell stated, was to “absorb them until they merely disappear…” This decade showed radical Seminole resistance. This pivotal decade would cement the Seminole Tribe of Florida as an established political entity, separate from the US Government and with its own sovereign agency.

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting to Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.