A Dark History at Egmont Key

Welcome back to our series on Seminole Spaces! In this series, we explore places and spaces important to Seminole culture, history, and tourism. Egmont Key is a small island located in Tampa Bay. Today, it is known as Egmont Key State Park and Wildlife Refuge. But, these sandy beaches hide a darker past. Currently, a number of entities and agencies manage the island. The Coast Guard occupies around 35 acres of the island. The Tampa Bay Pilots Association inhabits another 10 acres along the eastern shore. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service owns the rest of the island. They co-manage the park and wildlife refuge with the Florida State Parks Service. These entities work together to mitigate damage to the wildlife populations, bird sanctuary areas, and maintain the parks’ historic elements.

In our featured image this week, you can see the Egmont Key Lighthouse from the beach. The author, Deanna Butler, took the image in 2017. Below, is another shot taken on the key. You can see a defunct and dilapidated boat launch.

Egmont Key State Park and Wildlife Refuge

Egmont Key State Park and Wildlife Refuge is located at the mouth of Tampa Bay, southwest of Fort De Soto Beach. Established in 1974, Egmont Key is the only Refuge of the Tampa Bay complex open to public visitors. Approximately 200 acres, this tiny island is accessible only by boat or ferry. The island has no water, food, restrooms, or other amenities. Visitors bring their own water for this remote trip. Currently, it functions primarily as a wildlife refuge. The island provides refuge for box turtles, gopher tortoises, dolphins, and manatees. The south side of the island is a shorebird refuge. This protected nesting area supports generations of osprey, brown pelicans, white ibis, royal and sandwich terns, black skimmers, laughing gulls, and American oystercatchers. In the spring and fall, this wildlife area also provides habitat for other wintering birds migrating through Florida.

Although it is primarily a wildlife refuge, the island houses remnants of decades of former military installations. These include an 1848 lighthouse and six miles of brick path trails that wind through the island, remnants of Fort Dade. In the 1830s, shipping in and out of Tampa Bay increased. Subsequently, the number of grounded boats along the key’s sandbars increased, as well. The lighthouse was constructed to mitigate crashes. When it was completed, it was the only lighthouse between St. Marks and Key West.

Throughout the years, the military would use the island as a strategic point in the Civil War, the Seminole War period, and the Spanish-American War. The U.S. Military constructed Fort Dade on the key in 1898, as the Spanish-American War threatened. At the height of Fort Dade’s occupation, approximately 300 people inhabited the fort and it remained active until the mid 1920s. Afterwards, the Tampa Bay Pilots Association set up occupation on the island.

A Dark History

A dark history is woven into the story of Egmont Key; a Seminole history. In a previous post, we have explored the history of the Seminole War period. Although historians delineate between the First, Second, and Third Seminole Wars, Seminoles consider this period one long siege. Instead, “for the Seminole people there was only one war. They came under armed and organized attack from America in 1812, and the fighting only ended in 1858.” After the Indian Removal Act of 1830, pressures upon Seminole people became even harsher. The U.S. Government forcibly removed tens of thousands of Indigenous people from their homes, under the guise of ‘legality.’ This brutal and deadly practice decimated Native families. Seminoles were under increasing pressure to leave Florida, and open conflict with the U.S. Army resumed in 1855 with the final phase of the Seminole War (Egmont Key 10).

In the later half of the 1850s, the U.S. Army selected the island as a strategic location for a prison camp. Hundreds of Seminoles were imprisoned there before being transported north to the Creek Reservation in Oklahoma. Captured or surrendered Seminole were taken out of South Florida and initially held at Fort Myers. Then, they would be placed on the steamer Grey Cloud, before being transported to Egmont Key. After, the prisoners would be taken first to St. Marks, then eventually transported further north through New Orleans and up to Fort Gibson.

For many, Fort Gibson was the last stop on the Trail of Tears before being forced onto federal reservations (Egmont Key 12-13). Although no archaeological record remains of the internment, newspapers at the time referred to it as a stockade, or prison. Seminoles have referred to it as “The Dark Place,” “Our Alcatraz,” and a concentration camp (Egmont Key 11).

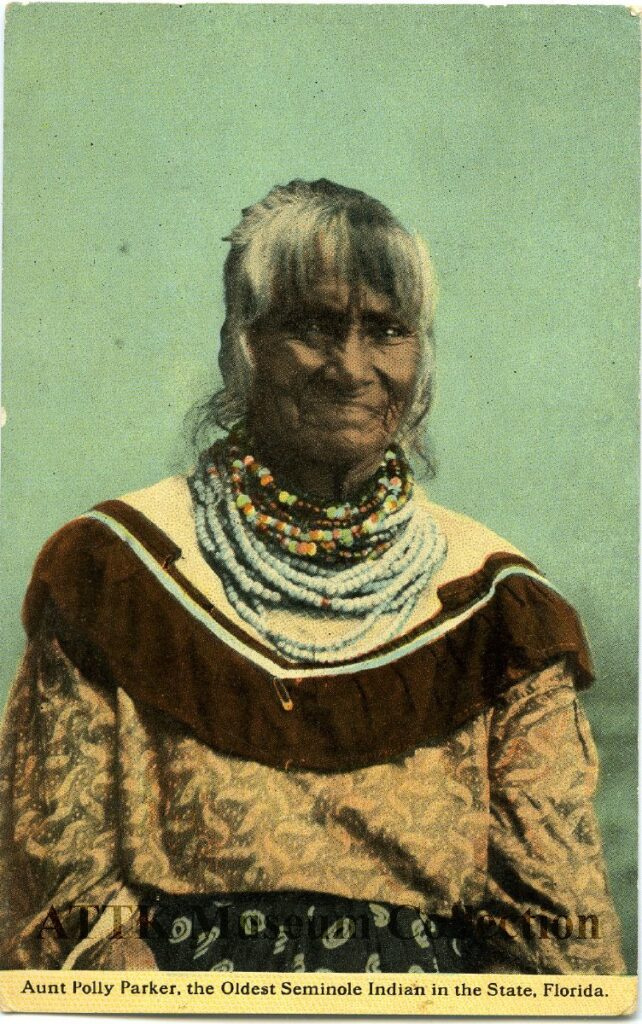

2003.15.49, ATTK Museum

Polly Parker

Like so many stories in Seminole history, among the darkness there is also a thread of resilience, hope, and survival that shines through. For the history of Egmont Key, the journey of Polly Parker (Emateloye) is the perfect example of that resilience and a fierce determination that would provide the foundation for the Seminole Tribe today. The U.S. Army captured Polly Parker on Fisheating Creek in 1856, and transported her north on the Grey Cloud (Egmont Key 16). The Grey Cloud was bound for New Orleans. Parker and other prisoners would travel up the Mississippi before joining the Trail of Tears. In 1858, Billy Bowlegs, Polly Parker, and 162 other Seminoles were held at Egmont Key. While at Egmont Key, she later recounted being held under armed guard in the stockade (Egmont Key 14). As the Grey Cloud travelled further, it stopped south of Tallahassee at St. Marks to refuel.

For many, this was just one more stop before the forced push northward. But for Parker, that was not how her history would go. After getting permission to gather medicine, Parker and a few other Seminoles escaped the Grey Cloud at St. Marks. Escaping a brutal forced relocation, Parker was still hundreds of miles away from home. Polly Parker walked almost 350 miles back to her home in Okeechobee (Egmont Key 17). Today, her descendants make up an important part of the Seminole Tribe of Florida. Seminoles like Parker, who resisted removal, escaped, or fled U.S. Army efforts would go on to build the Seminole Tribe we know today. Above, you can see a postcard featuring Polly Parker from the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collection.

Egmont Key: A Seminole Story

In 2016, a lightning-strike fire tore across Egmont Key. The fire revealed a number of archaeological artifacts previously hidden under plant material. The Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office (STOF-THPO), in conjunction with the Florida State’s Parks Service and U.S. Fish & Wildlife launched an archaeological survey to assess the damage, catalogue the artifacts, and create a comprehensive report of the Seminole history of the island. While undertaking the project, the sheer weight of the history became apparent. The STOF-THPO launched an ongoing project to preserve and bring awareness to these “forgotten stories of Seminole endurance and survival.” Due to the threatened nature of the island, the Egmont Key Project ensures that “even if Egmont Key is washed away, its history never will be.”

The STOF-THPO published a comprehensive digital book, Egmont Key: A Seminole Story, with the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum and significant Tribal Member contribution. A critical source for this post, we encourage you to read the full publication to further your knowledge of Egmont Key and the Seminole story. Below, you see burned palms present on Egmont Key. The author took the image in 2017 during a follow-up archaeological survey. In addition to the published book, the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki offers age-appropriate curricula on Egmont Key for high school students.

The Legacy of Egmont Key

Today, Seminoles work hard to preserve the history of Egmont Key, and the Seminole story that happened there. Since 2016, the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office has organized several trips to the island. Elders and descendants have the opportunity to see it for themselves, and to learn and experience more of the gravity of that history. Egmont Key: A Seminole Story features some of those trips, their stories and experiences preserved for future generations.

In a 2018 Seminole Tribune article, a different trip taken by Seminole Tribal Members was recounted. In it, Quenton Cypress, HERO Community Engagement Manager, explains the importance of keeping the history of Egmont Key alive. “It just shows the strength of the women in our Tribe,” said Cypress. “It helps us preserve our past and lets us know where came from [as Seminoles]..reminds us that we are not here just because of casinos and gaming. We are trying to get that information out there and get more Tribal members out there to know their past.”

Egmont Key Today

Today, Egmont Key is threatened by climate change, erosion, and human impact. In 1877, Egmont Key was a reported 580 acres. Today, the island barely passes 200 total acres (Egmont Key: A Seminole Story 35). This dramatic land loss is the result of sand erosion and sea level rise, an estimated 4 to 8 inches. In 2017, Hurricane Irma battered Egmont Key with recorded winds of over 91 miles per hour. This caused a massive loss of sand on the island, as well as the loss of many previously recorded archaeological items. The Gulf of Mexico is swallowing the key whole, and without intervention the island will cease to be. Preservation of the island is increasingly important. Egmont Key represents a desperately dark part of Seminole history, but also shows their continued perseverance, resilience, and survival in the face of eradication.

If you choose to visit, we urge you to further investigate the traumatic Seminole history of the island, and to give the space the reverence and respect it deserves during your time there. Many Tribal Members liken Egmont Key to “our Auschwitz” (Egmont Key 35). So, we encourage you to keep this truth at the forefront of your mind, and be respectful to that experience as you walk through this Seminole space.

Additional Resources:

Egmont Key: A Seminole Story. The Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal Historic Preservation Office. https://stofthpo.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Egmont-Key-Digital-book-web.pdf.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.

Jorge Martinez

Wonderful that this history will not be forgotten and light can be shed on it