Native Reel Cinema Festival and The Plume Wars

State Archives of Florida, via Florida Memory Project.

These days, Florida is all about the birds. Like we talked about a few weeks ago in a previous post, they are an important part of our ecosystem. Many conservation laws and efforts are in place to protect our feathered friends. But, it wasn’t always like this! At one time, the dangerous and high stakes business of plume hunting gripped the nation. The demand for plumage devastated bird populations in Florida. In a recent talk, Everett Osceola of the Native Reel Cinema Festival highlighted the historic role the Seminoles played in the plume trade, as well as the film inspired by plume hunting. Did you miss this special event? If so, grab some popcorn! This week, follow along as we talk about the history of the Plume Wars in Florida, the 1958 film Wind Across the Everglades, and the Native Reel Cinema Festival.

Native Reel Cinema Festival

Last month, Everett Osceola spoke at an event commemorating Audubon Day about the Plume Wars and the 1958 film Wind Across the Everglades. Osceola is a Cultural Ambassador for the Seminole Tribe of Florida. He is also the founder of the Native Reel Cinema Festival.

At the event held at the Savor Cinema in Fort Lauderdale on April 26th, Osceola spoke about the Seminole role in the plume trade. From a Seminole Tribune article, Osceola stated that Seminoles were initially hired as trackers to locate bird-nesting sites. “We would help these hunters, but after awhile it became troublesome because they were taking more than they should,” Osceola said. “Some of these birds we use for our ceremonies and we use some for our regalia. But they were becoming very scarce.” Additionally, Osceola discussed the 1958 film Wind Across the Everglades, featuring Cory Osceola and Mary Osceola Moore among its cast.

Established in 2014, the Native Reel Cinema Festival is a partnership between the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Historic Stranahan House. Their mission is to “utilize film as a medium to tell Native American stories and engage a larger population to encourage conversations of cultural diversity and respect.” They feature films that center indigenous stories, actors, directors, and bring them to the attention of a wider audience. With that greater exposure, people of all backgrounds can encourage, uplift, and appreciate indigenous films and engage in intentional and dynamic conversations. The Native Reel Cinema Festival is held annually in February at the Seminole Tribal Fair & Pow Wow. For updates about next year’s Tribal Fair, please visit here for updates. If you would like to know more about upcoming events and updates, follow the Native Reel Cinema Festival’s Instagram and Facebook.

Dangerous Fashion

“Snowy Egret, 01, NPS Photo” by evergladesnps

Florida without birds wading through ponds, or hanging out on our beautiful beaches, would be a place that many of us would not recognize. In the not so distant past, many species were in danger of going the way of the dodo due to the pillaging of bird plumes. Hundreds of thousands of birds were hunted for their feathers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The plumes were in high demand for decorations on women’s hats, military uniforms, and other fashion items. The snowy egret was highly sought after for its distinctive, fluffy breeding plume. The millinery centers in New York and London were the main consumers. According to the Smithsonian Magazine, it was “calculated that in a single nine-month period the London market had consumed feathers from nearly 130,000 egrets.” Wading birds were threatened in an unparalleled way, with entire rookeries destroyed in days.

As anyone knows today, it is difficult and time consuming to impede the forces of big business and the fashion industry. Far removed from the harsh realities of plume harvesting in Florida, the millinery trade in New York was worth around $17 million. Conservationists and activists tried fervently to put in place legal protections for the birds and shift public opinion. The Florida Audubon Society was formed, in part, to end the plume trade and strengthen bird conservation. The Florida Audubon Society successfully helped push through the Lacey Act in 1900. It prohibited the interstate trafficking of wildlife killed in violation of state laws. Then, the Florida state legislature outlawed plume hunting in 1903. But, demand for plumes did not stop, and the feather trade became more polarizing and dangerous. The state law was difficult to enforce, with few people available to hold poachers accountable for their actions.

Plume Wars in Florida

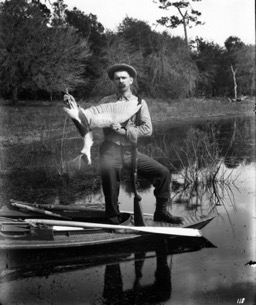

Plume Hunter posing with a black-crowned night heron, FL (State Archives of Florida), via Florida Memory Project

Public opinion began to turn in Florida. Ivy Stranahan, of the Stranahan House discussed in a previous post, was a staunch conservationist and schoolteacher. Ivy and her husband Frank Stranahan ran a trading post along the New River in Fort Lauderdale. They maintained strong ties with many Seminole people. Through relationships built at their trading post, as well as Ivy’s role as schoolteacher to many Seminole children, the Stranahans became an important bridge between the Seminole and white communities. Initially, the Stranahans also dealt in the plume trade. Ivy, a firm supporter of Seminole rights, eventually encouraged Frank to cease the sale and trade of feathers. She also encouraged Seminole trackers to stop aiding hunters in their searches. Changes in public opinion like this dealt a heavy blow to poachers looking for more rookeries.

The Florida Audubon Society worked diligently to stop the flow of feathers after plume hunting was outlawed in Florida. They appealed to fashion designers to further sway public opinion, and tried to increase enforcement of Florida’s law. They appointed game wardens tasked with stopping poachers to select places in Florida. These game wardens would patrol areas with known rookeries and try to enforce the state law. One such warden was Guy Bradley. Eventually, legislation caught up with public opinion with the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1913. An estimated 200,000 letters and telegrams were written to Congress about the treaty before signage. Although milliners in New York tried to find workarounds, the passage of this Act heralded the end of the feather trade in the US. By 1920, plume hunting was completely out of fashion.

Wind Across the Everglades

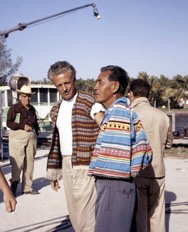

Cory Osceola and Nicholas Ray during the filming of “Wind Across the Everglades”

via Florida Memory Project

Released in 1958, Wind Across the Everglades was loosely based on the life, and eventual death, of Guy Bradley. Bradley worked to protect the fragile bird population from poachers. As a young man, he was actually a tracker who helped hunters find bird-nesting areas. At the age of 15, Bradley and his brother were scouts for the famous French plume hunter Jean Chevalier. Plumes were more valuable than gold. But, after the passage of the Lacey Act, Bradley saw the effects on the bird population and the importance of conservation. The Florida Audubon Society hired Bradley as a game warden for South Florida and the Everglades in 1902. He was one of the first game wardens in Florida. Bradley was responsible for patrolling the area from the Ten Thousand Islands on the west coast, across the Everglades, and down to Key West.

But, the dangers associated with plume hunting were not to be taken lightly. Bradley unfortunately died in the line of duty while confronting a plume hunter and his two sons in 1905. His death, and the subsequent acquittal of those responsible, became a national story. Bradley’s death galvanized the public, and helped shift public opinion even further against plume hunting. Only two years later, a DeSoto County game warden would also lose their life in an altercation with poachers. Winds Across the Everglades, directed by Nicholas Ray, is loosely based on Guy Bradley’s life and conservation efforts. Starring Christopher Plummer and Burl Ives as game warden and poacher, Wind Across the Everglades is a stunning look at an early 20th century story.

Cory Osceola and Mary Moore Osceola

Filmed in the Everglades National Park, Wind Across the Everglades also features actor and prominent Seminole leader Cory Osceola (above). In a previous blog post about the Power of Postcards, we mentioned Cory Osceola in connection with the Musa Isle Indian Village. A direct descendant of Seminole War hero Osceola, Cory Osceola would also be an important figure to the Seminole people. He lost his arm in a train accident in Fort Lauderdale in 1922, evident in these photos from the filming of Wind Across the Everglades. He eventually became the leader of Musa Isle, before leaving and starting his own tourist camp called Osceola’s Indian Village.

A prominent businessman, leader, and activist for the Seminole people, Cory Osceola played Billy One-Arm in Wind Across the Everglades. His daughter, Mary Osceola Moore, also played an unbilled role in the film. Their family is part of the Naples community. Read a fascinating account of Mary Osceola Moore here, written by her niece Tina Osceola. Here’s a little “behind the camera” story provided by Everett: Mrs. Moore and Mr. Christopher Plummer became great friends after filming. Mr. Plummer would send her a card every year on her birthday until his unfortunate passing.

Beyond the Feather Trade

Although the Plume Wars are a sordid piece of Florida history, they also showcase resilience. Due to those who fought and worked diligently for conservation, many endangered bird species have recovered their populations. Snowy egrets are found throughout Florida and beyond.

If you would like to support indigenous films, actors, directors, and more, make sure to follow the Native Reel Cinema Festival on Instagram and Facebook. We encourage you to seek out films and cinema that center indigenous actors, stories, and directors! Check back for updates on next year’s Festival, as well as the 2023 Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal Fair & Pow Wow.