The Power of Postcards

From gas stations to gift shops – postcards are everywhere. Cheap and easy to send, they are a novel way to document a vacation or trip. Sending postcards can share your trip with friends and family from afar. For just a few dollars (or less!), you can send a piece of a place to anyone you wish. According to the United States Postal Service, 485,907,000 postcards were sent by individual mailers in 2020. That’s a lot of postcards! But, did you know that postcards used to be a lot more popular than they are now? With the rise of social media and the internet, postcards and letters are actually on the decline.

However, at one time they were incredibly popular – and powerful! Postcards offer a glimpse of a place, culture, or moment in time that those receiving them may not have seen before. For some, it would be the first (or only) impression they would get. This week we are going to be talking about the power of postcards, and highlighting some postcards from the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collection. While they may seem like only snapshots in time, these postcards together paint a picture. Follow along to get a peek at the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s history of tourism through postcards.

What is a post card?

A postcard is a single, thin rectangular piece of cardboard or cardstock for sending messages without an envelope. The US Postal Service now has standards around the size and width of the cards themselves. A postcard generally needs to be 3 ½”x5” but no larger than 4 ¼”X6”. This qualifies it for the First-Class Mail postcard price. Letter prices were more expensive. Why does this matter? One of the reasons postcards became so popular, and have persisted so long, is due to the price. They are affordable for almost every person. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it could have cost as little as $0.01 to send a postcard. Although prices have changed over time, it is still relatively inexpensive to pop a postcard into the mail.

History of Post Cards

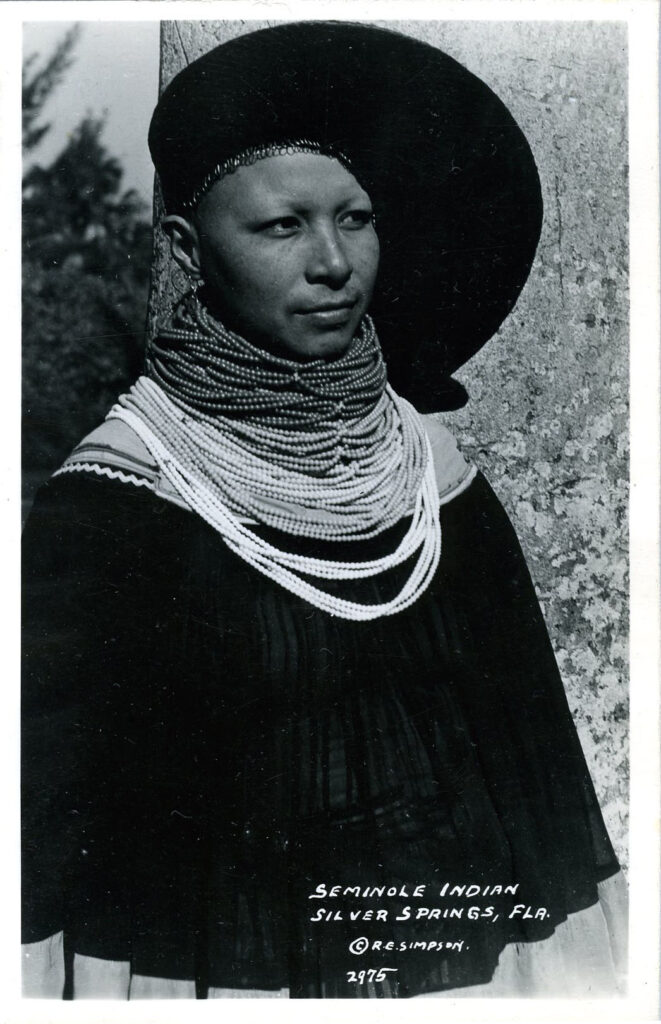

Mabel Frank, Real Photo PC, Catalog 2001.17.1, ATTK Museum Collection

Postcards as we know them now took a long time to develop. Mailing cards and government issued postal cards were used sporadically in the late 19th century. Exhibitions sold postcards for private collectors. Postcard collecting was and still is a very popular hobby known as deltiology. But, the beginning of the real postcard boom started in 1898. Congress signed the Private Mailing Card Act that allowed private companies to produce postcards at the same mailing rate as the US Government “postal cards.” Both cost one cent. But, certain constraints meant that postcards didn’t boom in popularity quite yet. Prior to 1907, the back of a postcard could only contain mailing information. If the front contained an image, it significantly impacted the area for the message. The writer would need to write over the image itself.

By the beginning of the 20th century, most postcards contained images on the front instead of a message space. But, a significant shift occurred in 1907 with the beginning of the Divided Back Era. In response to international changes to postcard standards, Congress passed an act that allowed for messages to be written on the address side of the card. Now, a divided back where one side contained the address and one side contained the message space was allowed. This freed space on the front for an image. The “Golden Age of Postcards” started because of this change. Postcard fever gripped the country. By the end of 1908 over 700 million postcards went through the US Postal Service. From 1905 to 1915 almost a billion postcards passed through the postal system annually. Others, like the one here of Mabel Frank in Silver Springs, FL, were sold in collector’s packs.

Real Photo Postcards

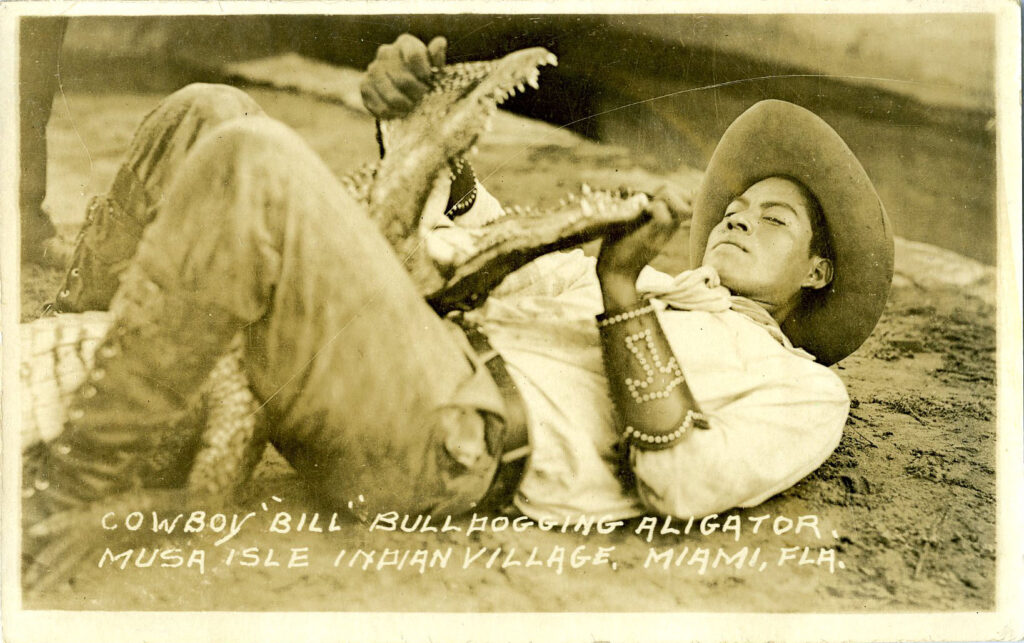

“Cowboy ‘Bill’ Bulldogging Alligator Musa Isle Indian Village; Miami, FL”, Catalog 2000.30.5, ATTK Museum Collection

Like with most historic items, the material and means of production say a lot about the item itself. Real photo postcards were just that – real photos. In 1903 Kodak released a new camera that allowed the general public to take photos the same size as the common postcard. Developed photos could be attached to blank cards. Kodak additionally provided a service starting in 1907 which allowed people to make a postcard from any picture they took. Finally, messages were permitted on the back of postcards that same year. As a result, the popularity of real photo postcards skyrocketed. Anyone could take a photo and turn it into a postcard. Some were mass produced, but the majority were taken by amateur photographers in real time. Real photo postcards also increased accessibility to photography in areas where it would otherwise be a luxury.

Here is a real photo postcard from the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collection. Cowboy Bill wrestles an alligator at the Musa Isle Indian Village in Miami, FL in the 1930s. These tourist villages were incredibly important to the Seminole Story, and a vital economic resource. In the face of a rapidly changing Florida, the Seminole people adapted along with a burgeoning tourism market. Alligator wrestling developed as a tourist show starting in the 1920s. Seminoles have hunted alligators for centuries, and this stylized wrestling show was designed for excitement. Learn more about Alligator wrestling here in a previous post.

Over time, technologies improved. Consequently, photos began to be enlarged and mass produced more easily. Real photo postcards were rendered obsolete once printing technologies developed, and were eventually replaced by linen and photochrome cards.

Linen Card Era

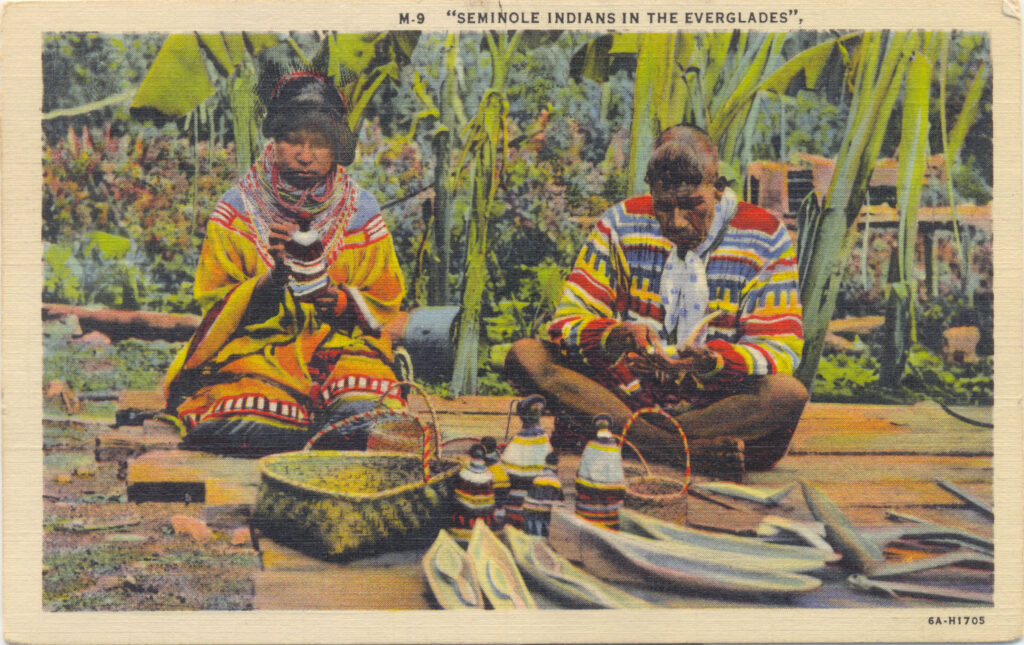

Catalog 2001.30.1, ATTK Museum Collection

Linen postcards represent another shift in postcard production. A reaction to the Great Depression, linen postcards are brightly colored, hyper-realistic, mass produced prints. This type of postcard allowed for faster production, and its appearance was eye-catching enough to entice someone out of their hard-earned pennies. Although not made of linen, these postcards have a textured surface that mimics the feel of the fine fabric. If you pick one up, you would be able to tell that it was a linen postcard by touch. This texture allowed for greater color saturation. Before these technological developments, it was not cost effective to print on such an uneven surface. Linen postcards were popular from around 1930 to 1945, and were replaced by photochrome postcards. Linen cards were mass produced from professional photos, then retouched. In many ways, the super saturated, bright colors glossed over the difficult reality of the Great Depression and WWII.

The purpose of the linen card was to sell rather than be fully authentic. The images originally came from black and white photos. Then, significant amounts of time were dedicated to altering, coloring, and retouching. Artists retouched by hand. Linen postcards were effectively paintings in many ways. The postcard here, circa 1939, is a good example of the bright, saturated color style seen with linen postcards. It shows a Seminole man and woman in traditional clothing making crafts while seated on a wood platform framed by banana trees. The woman is making a doll, and the man is carving a sofkee spoon. Brightly colored dolls, toy canoes, and baskets surround them. Interestingly, this postcard was actually mailed and included a message for the receiver. Mailed out of Miami, FL on February 25, 1939 it ended up in Cleveland, OH. That’s a long way from Florida!

Modern Photochrome Era

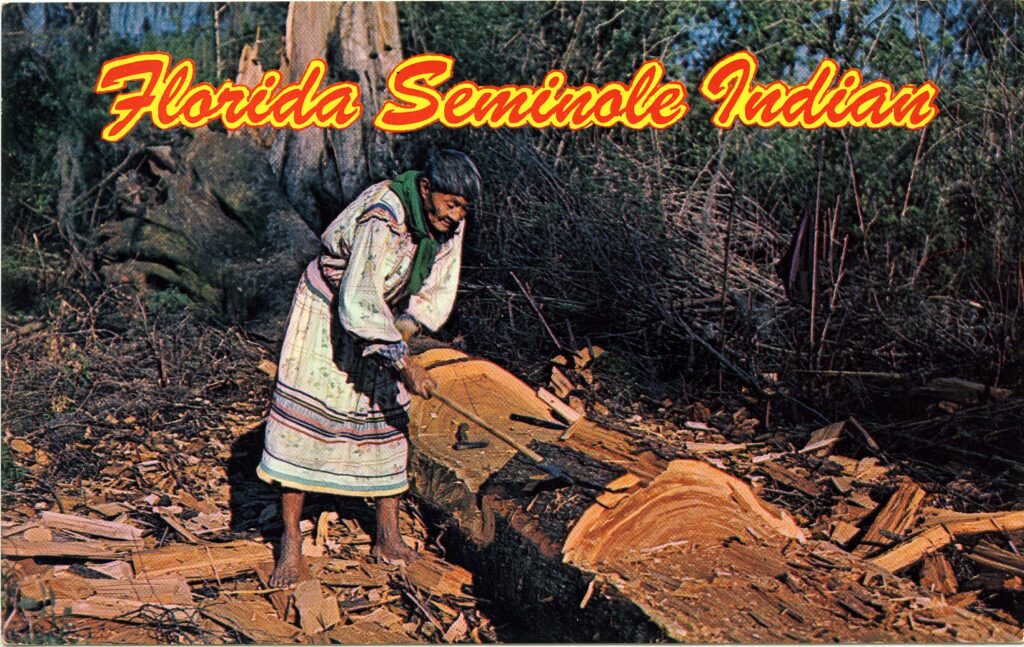

Charlie Cypress Canoe Carving, Catalog 2003.15.242, ATTK Museum Collection

First appearing in 1939, modern photochrome postcards are what we see today. Color photochromes replaced linen cards after WWII, as they were significantly cheaper to manufacture. Unlike linen postcards, photochrome postcards did not require any heavy retouching or artistry. While the process of making photochrome prints was not new, they did not edge out linen postcards until the mid 1950s. Modern photochromic prints are made from color photos and printed on glossy stock paper. Black and white negatives were used to make prints in a similar photochromic process in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

This process was transformed as technology shifted and color photography became better and cheaper to print with the introduction of CYMK process colors. In fact, ink printing still uses CYMK process colors today. CYMK process colors are Cyan, Yellow, Magenta, and Key (Black). The ease of printing color postcards, like the one shown below, significantly increased production capabilities. It also increased the color image quality.

In this postcard Charlie Cypress carves a canoe using an axe at Silver Springs, FL. Scrawling text across the top is clear, sharp, and bright. The image is clear, with crisp and defined colors. A mass-produced postcard, the trademark date is 1965, although this does not necessarily signify the photo date. Unfortunately, while postcards are still around, their popularity has significantly declined. With telephones, email, and now social media at our fingertips the demand for postcards has waned significantly in the last 80 years. So, while technology has caught up, the demand for postcards has not returned.

Seminole Tourist Camps

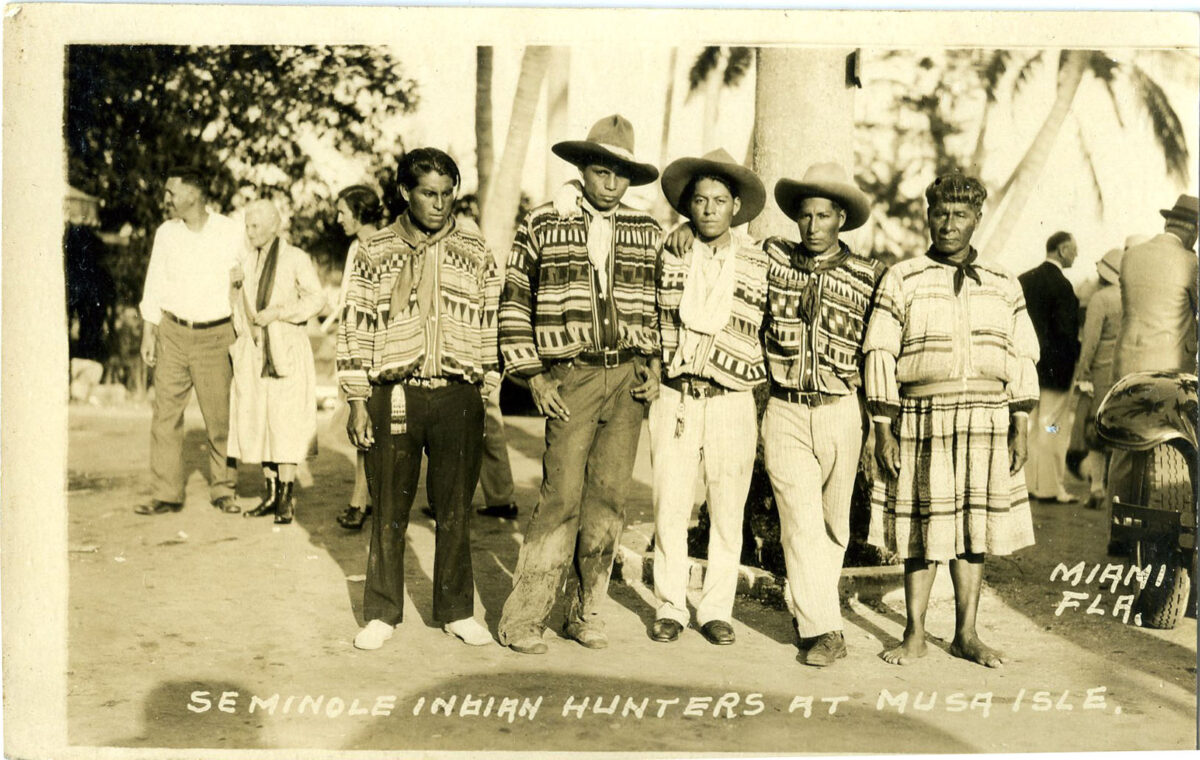

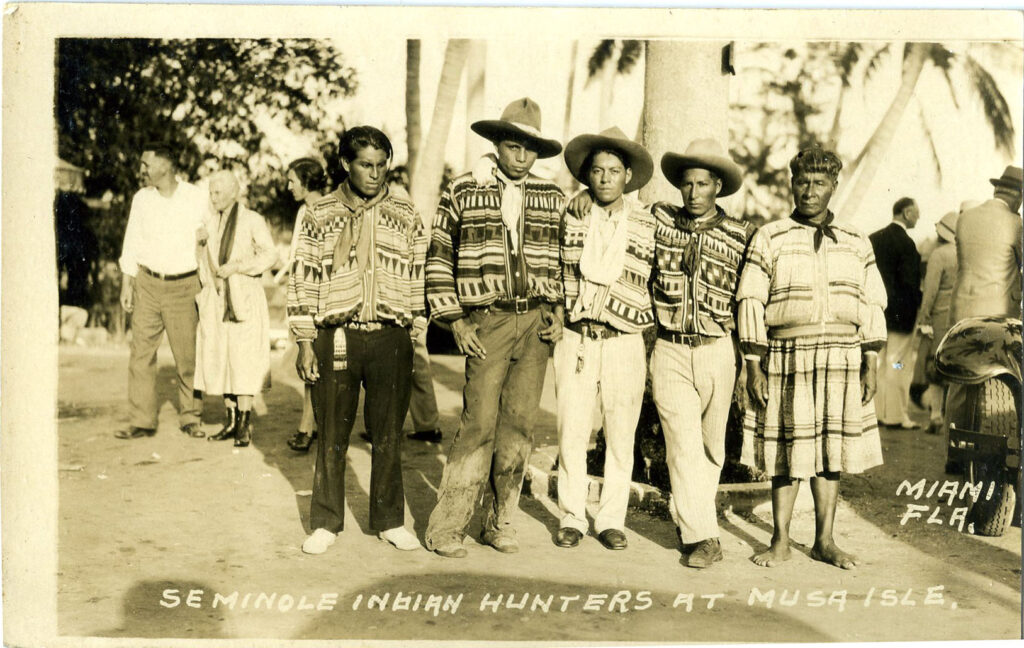

At Musa Isle, 1930s, Catalog 2000.30.1, ATTK Museum Collection

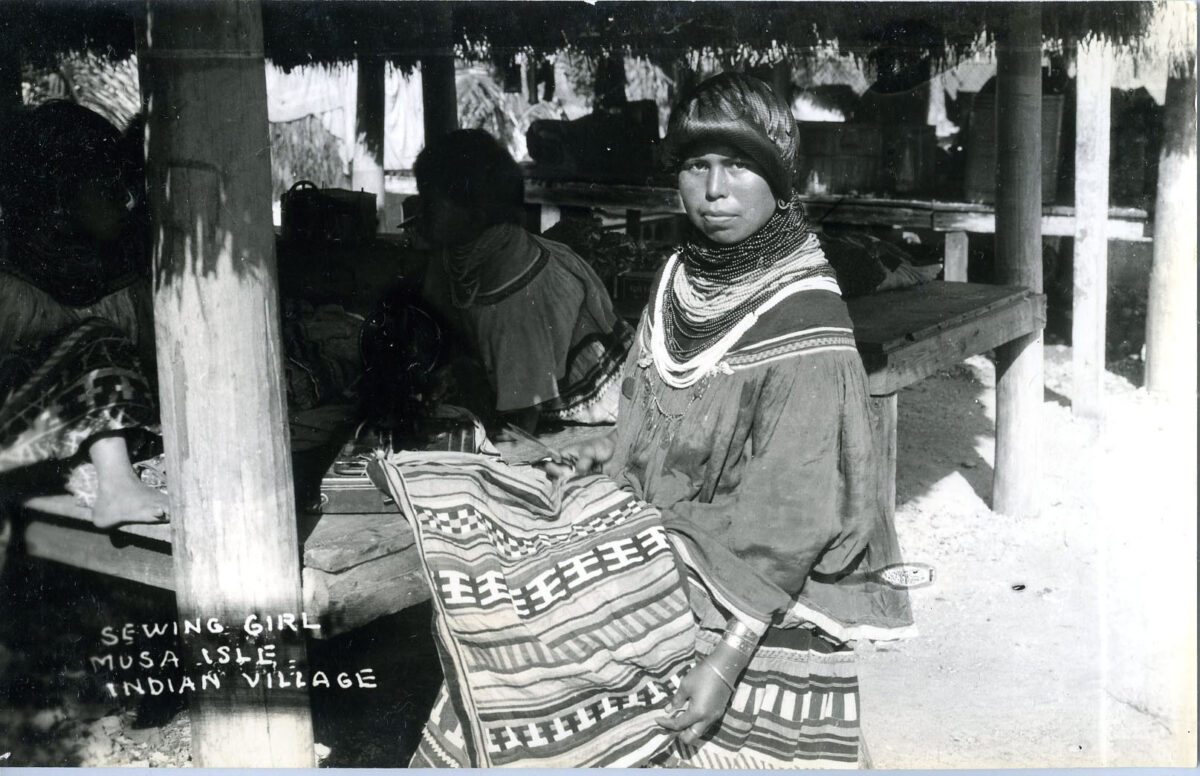

With the end of the hide/pelt trade and trading posts, the Seminole people were forced to adjust to a changing world. This transition was difficult, coming directly after the fear and pain-filled Government Relocation efforts of the 19th century. Seminoles made their homes at tourist and exhibition camps along the Tamiami Trail and elsewhere in Florida and sold dolls, baskets, patchwork clothing, and wood carvings. They flourished from the 1920s until through the 1960s. These tourist camps represented just one more way the Seminole people persevered through incredible hardships. You can read more about early 20th century experiences here in a previous blog post. Also, stay tuned for a more in-depth dive into Seminole tourist camps next week!

This postcard is a real photocard of five men posing in traditional patchwork clothing at Musa Isle in Miami, FL. Generally regarded as one of the first Seminole tourist camps, the Musa Isle Indian Village opened in the early 20th century. A long-time tourist attraction, it was located at 27th Ave on the Miami River. Cowboy Bill, shown above wrestling an alligator, stands with the group, . Cory Osceola stands to the left. The great-grandson of Seminole War hero Osceola, Cory Osceola would be an important Seminole businessman, activist, and leader throughout his life. Cory Osceola lost his left arm in 1922 in a train accident. This, and the presence and look of Cowboy Bill, suggest this photo is most likely from the 1930s. Scroll to the top of this page for a better look at this photo.

What about now?

Tourism is an incredible piece of the Seminole story. Through some of these postcards, you can see snippets of that history. By looking back, we can see how powerful these little cards were. These postcards shared images of the Seminole people, their culture, and bolstered Seminole economic agency by supporting tourism and tourist camps. Through the struggles of the late 19th and early 20th centuries they documented pieces of that story, and shared them beyond the state of Florida. Additionally, they serve as an important reminder of the resilience and perseverance of the Seminoles. Look at more postcards here in the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Online Collection.

But, these post cards are not the only ones with power. Even though not many are sent today, they’re great to collect, even if you aren’t a full-fledged deltiologist. Do YOU have a favorite postcard that made an impact on history or you personally? Share with us in the comments!

Additional Sources:

Greetings From The Smithsonian: A Postcard History

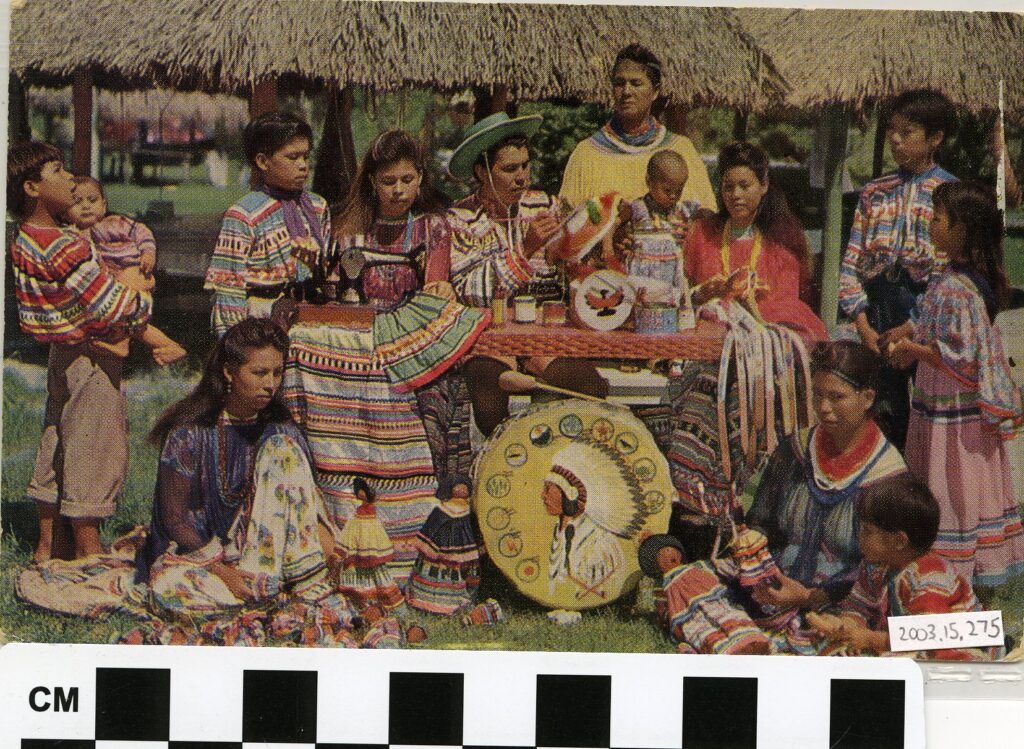

Musa Isle Postcard, 1950s, Catalog 2003.15.275, ATTK Museum Collection

Pingback: The First Seminole Tourist Camps - Florida Seminole Tourism

Pingback: Early Florida Transportation leads the way for Tourism - Florida Seminole Tourism