The First Seminole Tourist Camps

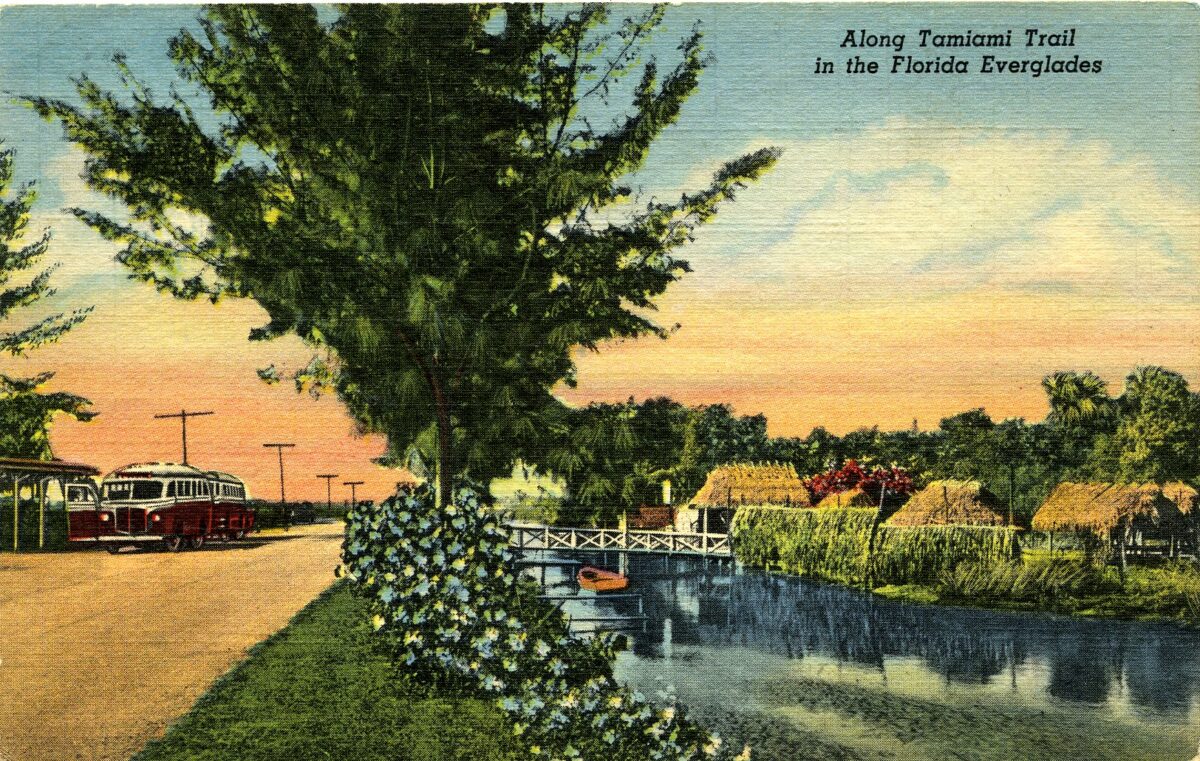

Last week, we talked about the power of postcards and how they offered a small glimpse into life in the early to mid-1900s. Many of the postcards we shared featured images from Seminole tourist camps. During the first half of the 20th century these tourist camps, or tourist villages, were dotted along the Tamiami Trail in hopes of enticing visitors.

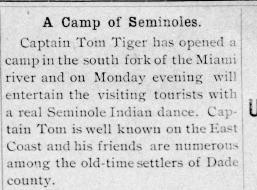

Excerpt from “A Camp of Seminoles”, Miami Evening Record, March 7,1904

This week, we will dive deeper into the history of how these camps came to be, and how they are a symbol of Seminole resilience in a changing world. Exhibition shows like alligator wrestling or canoe carving brought excitement. Traditional crafts like palmetto fiber dolls, patchwork, sweetgrass baskets, and toy canoes were sold. These camps were most popular from the 1920s through the 1960s and their impact can still be seen in Seminole tourism today. Tourist camps were also an integral part of tourism in Florida during the period, and made their mark on Florida history.

On March 7th 1904, the Miami Evening Record published a news article titled “A Camp of Seminoles.” This innocuous, single column story may be evidence of the first Seminole tourist camp. Started by Captain Tom Tiger, this camp boasted “a real Seminole Indian dance.” The opening of the camp was described as “the first time in the history of the Seminoles in Florida that they have ever engaged to come before the public.” Chickees were built in the camp, and tourists would be able to pay for a guided canoe trip into the Everglades. Although Captain Tom Tiger died sometime before 1907, the legacy of this possible first Seminole tourist camp can still be seen today. This, and other tourist camps like it, were a vital economic resource for the Seminole people during the struggles of the early 20th century.

Indian Removal Act

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson pushed the Indian Removal Act through Congress. The intention of the Act was to free up fertile land in the Southeastern United States for white settlers. But, that land was already being lived on. What followed was the fragmentation, genocide, and forced relocation of tens of thousands of native people from their ancestral homelands. While treaties in the past had been used to displace specific tribes, the Act strengthened the power of the US government over native people. Over 60,000 people were forced from their homes in the Southeast in a 20-year period and relocated. The majority were from the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, and Seminole nations. While not the only, the infamous “Trail of Tears” is an example of this tragic forced migration. Thousands died in this forced migration and others like it, and the scars are still present throughout native communities.

Seminoles are the only tribe that has never signed a peace treaty with the US Government. By the end of the 1840s, the Seminole resistors were the only native people left in their ancestral homelands in the Southeast. Even though they faced removal and genocide, they never faltered. This was known as the Seminole War period, and major battles were fought between the Seminole people and the US Government. Utilizing guerilla warfare tactics, Seminoles retreated to the Everglades to evade US troops. While over 3,000 were captured and relocated to Oklahoma, a small number were able to survive. Military actions against Seminoles cost the US $40 million dollars and the lives of 1500 troops, the most costly military action in US history at the time. At the end, historians estimate that only a few hundred unconquered Seminole men, women, and children were left hiding in the Everglades.

Trading Posts

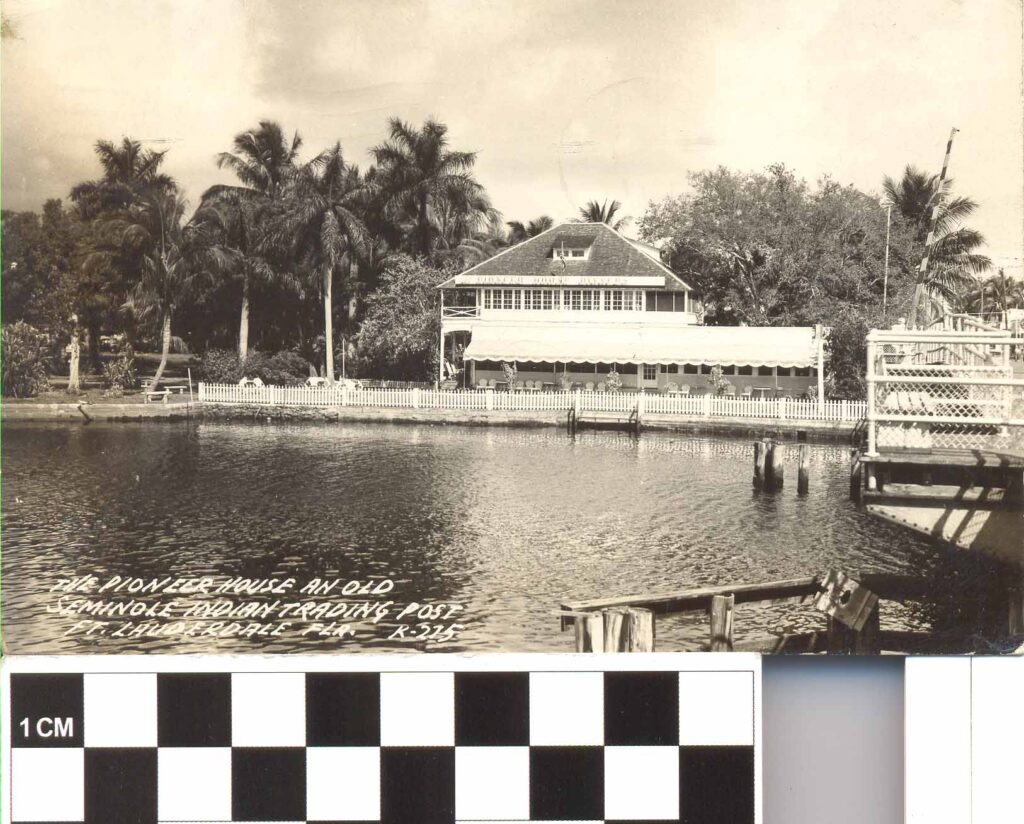

Real Photo Postcard of Stranahan House, 1947, 2005.70.1, ATTK Museum

After the Seminole War period, distrust and wariness ran deep. But, the US had given up, and Seminoles were an unconquered people. Life continued in the Everglades, although the impact on families, homes, and lives being torn from them was far reaching. Seminoles lived in family camps of traditional chickees made from cypress and thatched with palmetto. Intentionally isolated from the rest of Florida, they held strongly to traditional ways of life and culture.

If you remember from our Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum’s Virtual Tour post from a few months ago, this is when relationships with local trading posts began. The Stranahan House, featured in a permanent exhibit, was one of these trading posts. If you would like to the visit the Museum to see the exhibit in person, check out their website for details here. In operation from 1894 to 1906, the Stranahan Trading Post and General Store was located on the New River in Fort Lauderdale. The Historic Stranahan House Museum is Fort Lauderdale’s oldest and most historically significant surviving structure and is open for visitors!

Trading posts were important contact points between Seminoles and white settlers. Seminoles used canoes to traverse canals to trading posts even from the deepest parts of the Everglades. Living in the Everglades was rough, but trading posts offered economic opportunity. Alligator hides, skins, feathers, produce, and crafts could be traded for food, silver, or convenience items. Over decades, relationships developed. At the Stranahan House, Ivy Stranahan offered informal school lessons to Seminole children that respected cultural traditions. These relationships with non-Seminoles would sow the seeds of what became the first Seminole tourist camps only a few years later. Trading posts like Stranahan House, Ted Smallwood’s Store on Chokoloskee, or Brown’s Trading Post were vital to the development of South Florida. Additionally, trading posts and tourist camps would become important pieces of Seminole history.

A Changing Florida

A rapidly changing Florida hastened the end of the trading post era. Unlike the Seminole people, white settlers had no desire to embrace the difficulties of the Everglades. Instead, they sought to develop it. Prior to this period, the Everglades was an interconnected wetland prairie with a unique sheet flow supporting a diverse ecosystem. Although that ecosystem is still very diverse, a series of developments in the 19th and 20th centuries severely altered the landscape and health of the Everglades. As water swelled out of Lake Okeechobee in the wet season, a vast slow-moving river wound down the Florida Peninsula to the ocean. Drainage projects started to be funded to stem the flow of water and hasten development. The US Army Corps of Engineers built a massive dike around the lake to prevent overflow. People began flocking to Florida, and with them canals were constructed to further prevent flooding.

This fragmentation of the Everglades resulted in the end of trading posts. The natural landscape had been significantly altered, and with it the ability to move freely among the water. Development brought even more settlers and tourists to Florida. But, with trading posts disappearing, Seminoles once again had to be resilient and adapt. Tourist camps began to pop up in populated areas and on the newly constructed Tamiami Trail. Survey on Tamiami Trail began in 1915, with it the dream of connecting Tampa, Fort Myers, and Miami. Officially completed in 1928, the Tamiami Trail was the last puzzle piece needed to bring about a tourism boom in South Florida.

The Rise of Tourist Camps

Musa Isle Brochure, 1950s, 1997.10.16, ATTK Museum

With the influx of people and the need to adapt to the changing landscape, Seminole exhibition villages and tourist camps were established. While Captain Tom Tiger’s camp discussed above was possibly the first, it would not be the last. From small roadside family camps to large complexes, many people tried to hammer out a living with tourism during this economically tenuous time. With their ability to live as they had disappearing, it became a necessary means of survival. This new way of living came with challenges. It is not hard to imagine the difficulty of surviving on the whim of tourist dollars.

Alligator wrestling, hunting exhibitions, wood carving, canoe displays, and more brought in roadside travelers. Postcards, photo opportunities, and crafts were sold along with these exhibitions. Some of these camps only operated seasonally, with many people living further inland and travelling back and forth. In 2020, two donations came to the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum that offered a window into this experience. One was purchased at a roadside camp on Tamiami Trail, and the other purchased from an artisan on Big Cypress. Both paint a multifaceted picture. To read more about these two early 20th century stories, here is a previous blog post.

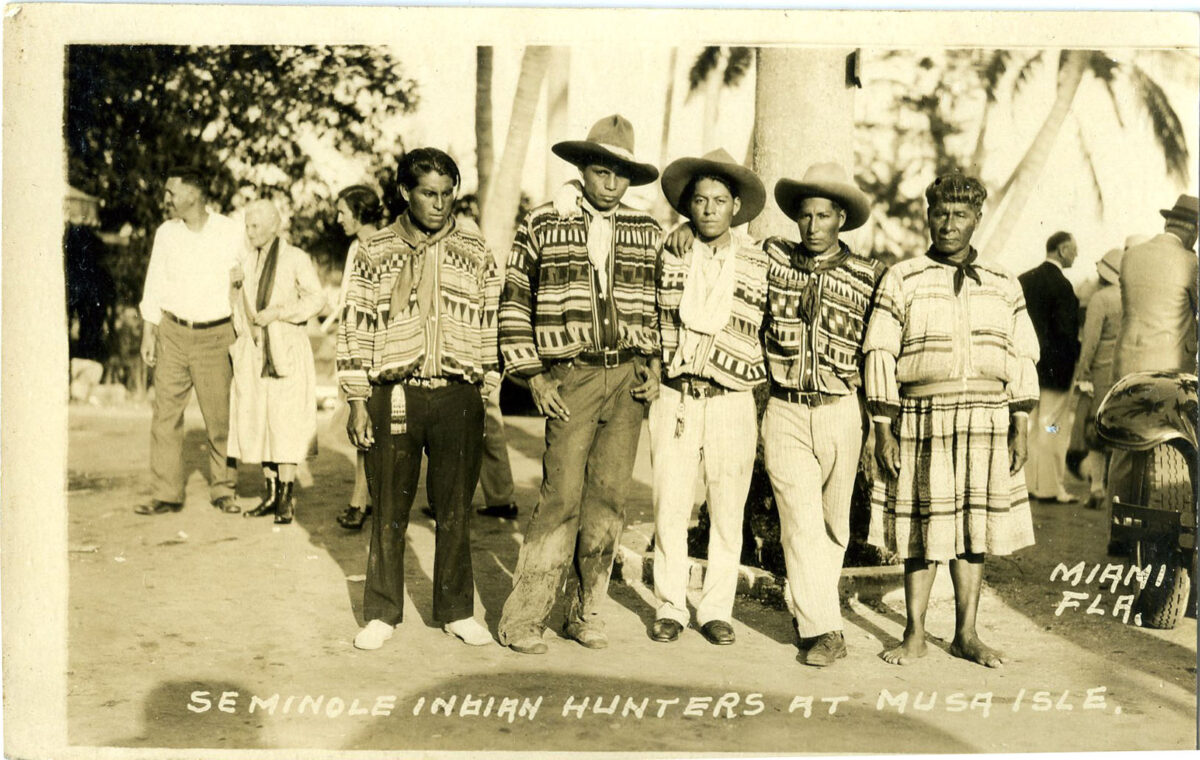

Musa Isle Indian Village

Shown in many of the postcards from last week’s post, Musa Isle was one of these exhibition villages that opened in Miami 1921 and was one of the most famous of these tourist camps. A large number of photos, postcards, and marketing material was also produced from Musa Isle. Much of it can be found in the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collection. To the right, you can see a 1950s era brochure with directions to Musa Isle. It contains a list of recommended Florida attractions. Interestingly, the brochure also features a totem pole. While totem poles were not traditionally Seminole, they were carved and sold in Seminole tourist camps. Through the tourist camps, Seminole people were exposed to other native cultural traditions. They then joined and melded these with their own forms of art. A number of totem poles like this exist in the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collection.

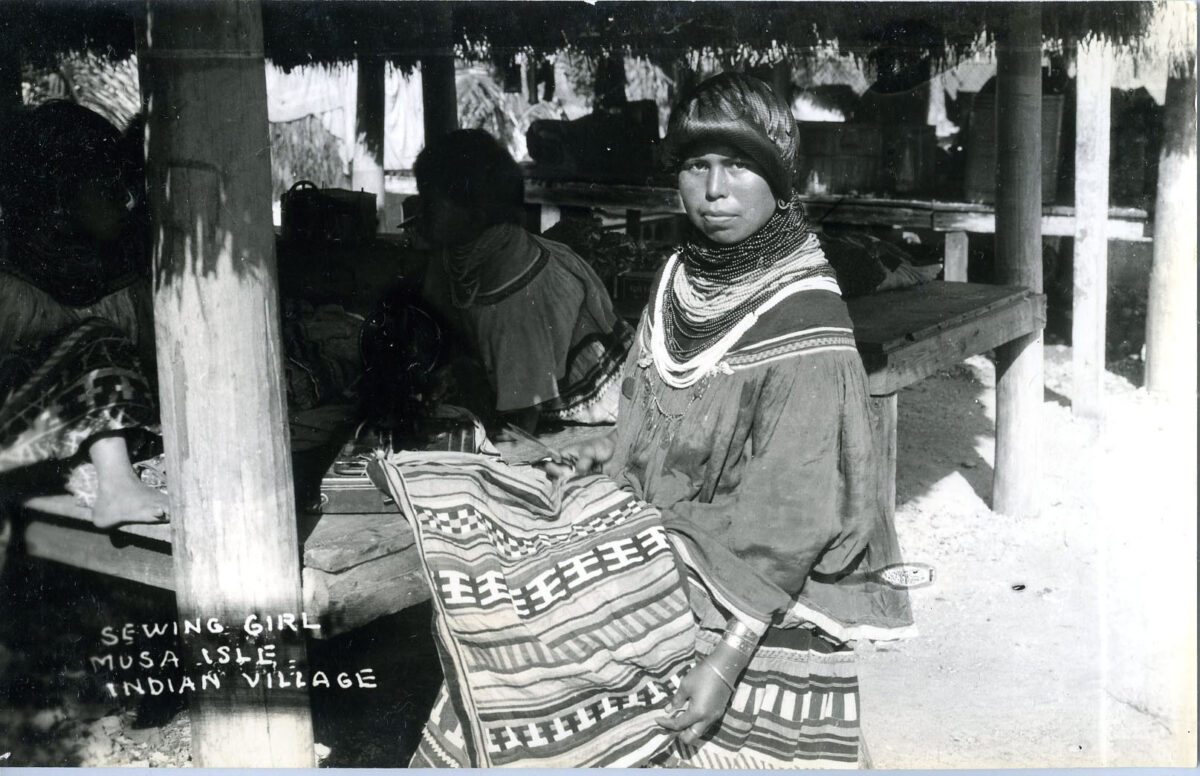

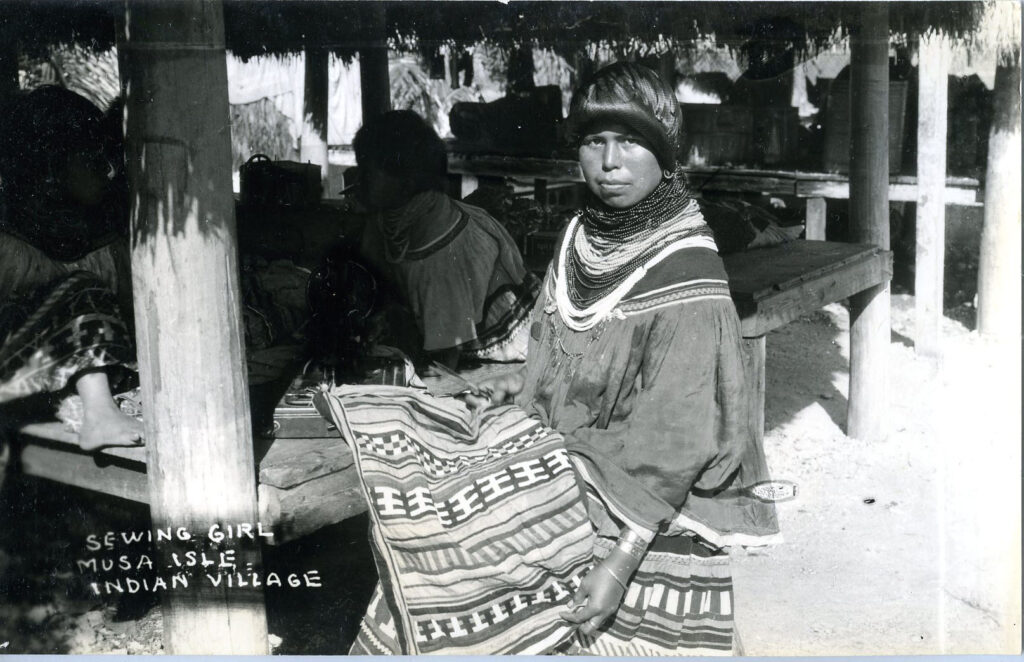

“Sewing Girl Musa Isle Indian Village”, 1930s, 2002.10.5, ATTK Museum

Tourist camps like Musa Isle offered a wide range of activities to entice tourists. Alligator wrestling shows brought action and thrills. Palmetto fiber dolls with traditional patchwork clothing could be purchased for 10 cents a doll. These dolls could be male or female, with stylized faces on palmetto fiber. Complex sweetgrass baskets featuring a doll head on top were also sold. Other crafts like toy canoes, patchwork clothing, and wood carvings were also for sale.

Seminole women would work under chickees on patchwork, make baskets, cook food, and sew dolls and other crafts. At Musa Isle, you could take a cruise on the Seminole Queen Jungle Cruise for a sightseeing tour in hopes of a glimpse of the wild Everglades. A real photo postcard can be seen to the right of a Seminole woman sewing patchwork at Musa Isle in the 1930s. This postcard was part of a pack of 6 for sale.

Seminole Tourism Today

Early 20th century exhibition villages and tourist camps provided economic opportunities for Seminole people. Entire families worked either sharing cultural activities, selling crafts, or in the larger operation and management. The impact of these tourist camps is seen not only in Seminole history, but how the Seminole Tribe of Florida tourism operates today.

By the 1960s, it was a common economic venture for Seminole people. After the formal organization of the Seminole Tribe of Florida in 1957, the first business venture of the tribe was the Seminole Okalee Indian Village and Arts and Crafts Center. The location of the Seminole Okalee Village would eventually become the site of the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Hollywood, FL. Once this was established, tourism began to centralize around the reservation land. Ultimately casinos, which the Seminole Tribe of Florida is now known for, would explode the economic agency of the Seminole people.

Seminole tourism today holds many whispers of this early tourism trade. Alligator wrestling shows still bring heart-pumping thrills. On Big Cypress at the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum, the village crafters sell dolls, patchwork, and wood carvings to museum visitors. The Seminole Hard Rock Hotel and Casino features art and events for visitors to learn more about Seminole culture. The blend of enterprise, tourism, and culture is a common thread through all of Seminole history. Adaptability is the driver of success, and Seminole tourism is a prime example of this. While keeping culture and traditions at the forefront, Seminole tourism has also modernized to keep up. Now though, instead of only Pointing Man signs to lure in visitors, Museum events and social media marketing draw people in. If that doesn’t get you to visit, what will?

Looking for more?

To visit the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki-Museum, please inquire here.

To purchase Seminole crafts, either visit the online marketplace, schedule a museum visit, or check back for updates on the American Indian Arts Celebration (AIAC) November 4-5, 2022.

Pingback: History of Tamiami Trail - Florida Seminole Tourism

Pingback: The History of Seminole Sweetgrass Baskets - Florida Seminole Tourism

Pingback: Tom Tiger's Camp: The First Seminole Tourism Enterprise - Florida Seminole Tourism

Pingback: Florida's Native American Heritage Trail - Florida Seminole Tourism