Cruise Through Remarkable Seminole History on the Miami River

Welcome back to the latest installment in our Seminole Spaces series! This series explores the places and spaces significant to Seminole history, tourism, and tradition. In the past, we have looked at a wide variety of spaces both in Florida and out, including the Ten Thousand Islands, Trading Posts, Chickees, and the Stranahan House. Today, get ready to dive in! We are exploring the importance and impact of the Miami River, a vital waterway in South Florida that had a marked impact on the Seminole tourist industry.

In our featured image, you can see a postcard depicting a Seminole family in a dugout canoe on the Miami River. The original image was most likely taken around the early 1900s, given their clothing. The man also wears a feather in his hat. Feathers such as these would fall out of fashion by the 1920s, due to the Plume Wars. But, they were a part of Seminole traditional dress.

The Miami River Falls

The Miami River is a 5.5-mile river running from the Miami Canal at its beginning and draining into Biscayne Bay. It winds through downtown Miami. Prior to human intervention, the Miami River looked much different. A freshwater river, the Miami River was fed by the Everglades as well as tributaries and natural springs that flowed into it before it eventually emptied into Biscayne Bay. Originally, it was formed by a series of rapids, where water flowed over a rocky ledge from the Everglades about four miles from its mouth.

Before these drainage projects would permanently alter the landscape, “the Miami River Rapids fell six feet over the course of four hundred to five hundred feet. During the rainy season, the water over the falls had a velocity of fifteen miles per hour. This natural phenomenon has been described as ‘a scene of enchantment.” (West 40) Below, you can see two images taken pre-dredging, which show the force of these currents.

Florida Memory Project

Florida Memory Project

These rapids made river travel up and down treacherous, especially during rainy season. Often, Seminole who “came into Miami from the Everglades traveled down Wagner Creek, especially where conditions were such that they could not navigate the rapids.” (West 42) This tributary and the Miami River became an early site for tourist camps, with Seminole camps being established next to alligator farms in some of the earliest incarnations of the Seminole tourist trade.

A series of dredging projects began in 1908, spurred by the arrival of the Florida East Coast Railway in 1896. These dredging projects, as well as the construction of the Miami Canal, began in earnest in 1909. They would destroy the natural rapids and forever alter the waterway. Dredging and drainage would continue through 1930, leading to saltwater intrusion and pollution.

On the River

Prior to Spanish contact, Seminole ancestor tribes were well established along the mouth of the river. The Tequesta occupied the area around Miami and Biscayne Bay from approximately 500 BCE through Spanish contact. This is evidenced by a series of archaeological sites, the most notable of these the Miami Circle located at the mouth of the Miami River.

Predominantly a coastal culture, they “utilized canoes both in the oceans as well as deep into the Everglades. Middens also show that they were part of a vast trade network, providing ‘items from the coast such as pumice, marine shells, shark teeth, and dried whale meat in return for items like stone tools and minerals for making paint.’” Ponce de Leon would record first contact with the Tequesta, and describe Biscayne Bay, in 1513.

Following the decimation of the Tequesta and other Seminole ancestor tribes, waterways like the Miami River were still vital arteries for travel and trade. Settlements along the Miami River would become sporadic for a number of centuries, with missions, trading posts, and other settlements failing to last. This would all change in 1836, when Richard Fitzpatrick would build a plantation on the north side of the river.

The U.S. military would establish Fort Dallas on the plantation, which would operate during the Second and Third Seminole wars, as well as the Civil War. The location was a strategic choice, providing not only protection for these Miami settlers from Seminoles, but also controlling travel into and out of the Everglades into Biscayne Bay. Below, you can see an image taken during the Ingraham Expedition in 1894. It shows the remnants of Fort Dallas, then owned by Julia Tuttle, on the north bank of the Miami River.

Florida Memory Project

The Beginnings of Musa Isle and Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens

The town of Miami was incorporated on the banks of the Miami River in 1896. That same year Henry Flagler would open his sumptuous Royal Palm Hotel at the mouth of the river, where the Florida East Coast Railroad terminated (West 40). The tourist boom had begun. Tourists from the hotel also began to take small excursion boats up river, “such as the popular Sallie upriver to the Richardson grove.” (West 40)

The grove, located on a small island between the north and south forks of the Miami River, was settled by the A.J. Richardson family in 1897. It would eventually become Musa Isle. Quickly, more and more tourist sites began cropping up along the river, and “the excursion boats brought tourists to these outlying river attractions, making continuous daily runs upriver as far as the rapids.” (West 42)

Ownership of Musa Isle would change hands in 1907 when it was purchased by John A. Roop, who sought to further expand and develop the grove. But, the grove would not last. “As the drainage programs escalated in the Miami area and the Miami canal opened into the Miami River in 1908, the trees withered for lack of water.” (West 43-44)

At the same time that Musa Isle was grappling with the loss of the grove, on the south fork of the river another early tourist spot was developing. Henry Coppinger Sr., a landscape designer, purchased ten acres in 1911 and began planting lush foliage and exotic plants. It would eventually become Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens, and home to famous alligator wrestler Henry Coppinger Jr. Although alligator wrestling is long rooted in Seminole tradition, Coppinger would be the one to make it explode on the tourist scene (West 45).

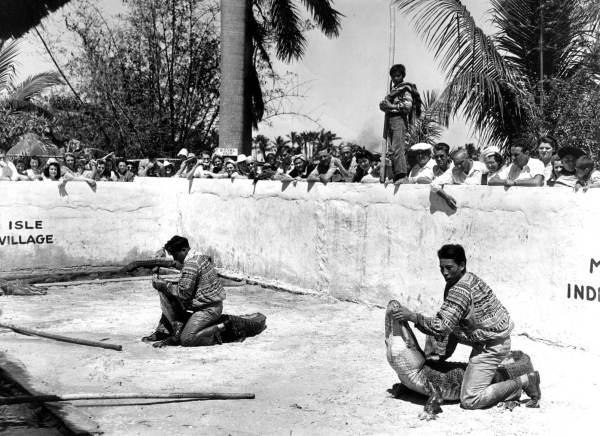

A Seminole Indian wrestling an alligator at Musa Isle, Miami, ca. 1940s

Seminole Tourism Begins on the River

As Miami developed around them and more and more settlers and tourists streamed into Miami, conditions for the Seminole rapidly worsened. Seminole camps and settlements were seized by investors, and the changing landscape around them made traditional subsistence difficult. Trade became impossible with the waterways being cut off by endless drainage projects, and free movement became difficult. Forever resilient, Seminoles were forced to adapt to these changes. Some, like those under matriarch Annie Jumper Tommie, “began to pick crops for white farmers, often on land that they had once farmed themselves.” (West 46)

Coppinger’s Tropical Gardens formally opened as a tourist destination in 1917. Only a few weeks later, a chilling freeze would destroy the succulent gardens. The first Seminole camp would be established at the gardens that same year, partially in part as a necessary pivot to garner tourism interest following the garden’s destruction. The family of Jack Tigertail would begin residence at Coppinger’s during the tourist season beginning in 1918. A popular figure in Miami, Jack “spoke English fairly well and could probably read and write like his brother Charlie. [He] was very visible and involved in local affairs.” (West 48)

Not to be outdone by his competition, Roop leased a portion of Musa Isle to Seminole entrepreneur Willie Willie in 1919. Willie Willie established the Musa Isle Trading post and Seminole village. In addition to the tourist attractions, he would foster a robust trade establishment for white and Seminole hunters alike. Willie and his father, Charlie Willie, also operated another trading post in the Everglades. They “bought the Indian’s hides at that location and shipped them in to Willie Willie’s Musa Isle Post. There they sold directly to the market, eliminating the usual non-Indian middleman and making a huge profit.” (West 49).

The Seminole Queen

At Musa Isle, a unique facet of the tourist experience could be found on the Seminole Queen. It was the only boat to stop at the Seminole village at Musa Isle, and success at the tourist spot depended on an enticing boating experience. Advertised as a jungle cruise, brochures for the Seminole Queen would talk up the Musa Isle tropical gardens, luring in tourists with descriptions of palms, citrus, and bananas. The Seminole Queen’s journey on the Miami River was an integral part of Musa Isle’s appeal, and was an incredibly popular attraction in itself. Below, you can see a postcard depicting the Seminole Queen, with its numerous advertisements emblazoned on the side.

2003.15.278, ATTK Museum

Seminole Tourism Develops

What would begin in the early days of the 20th century would have lasting effects on Seminole tourism and the trajectory of Seminole history. Although not the only Seminole tourist attractions at the time, Musa Isle and Coppinger’s were incredibly famous and both operated for decades. Willie Willie, who guided those early days of Musa Isle, encouraged other Seminoles to camp there and become involved in the attraction. Although his interests at Musa Isle would end in 1922, Seminoles would be involved in the venture through to its closing in the 1960s.

Tourist camps such as these show a pivotal moment for Seminoles, as they adjusted to the shifting landscape around them. They are evidence of the Seminoles’ enduring resilience and steadfast commitment to their culture, traditions, and history. Entrepreneurial ventures would pave the way for Seminole independence, which would eventually lead to federal recognition and the Seminole Tribe of today.

Looking to learn more about early Seminole tourist camps like Musa Isle and Coppinger’s? Check out these previous blog posts:

1910s-1920s: Tourist Attractions Show Seminole Resilience

Seminole Tourism Expansion in the 1920s

The First Seminole Tourist Camps

Additional Sources:

For the purposes of this article, the book below was accessed digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting To Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.