Seminole Spaces: Chickees

Welcome back to our intermittent series on Seminole Spaces! This series explores places and spaces important to Seminole history, culture, and tourism. Previously, we have looked at places like Lake Okeechobee and Okalee Village. This week, join us to learn about a different kind of Seminole space: chickees! Prolific across South Florida, chickees are traditional Seminole houses. Chickees are a fascinating look into Seminole architecture, and how it is reflected in Seminole tourism and history. While the elements may seem simple, “the architectural and cultural significance of the chickee lies beyond the outward appearance” (Dilley 1).

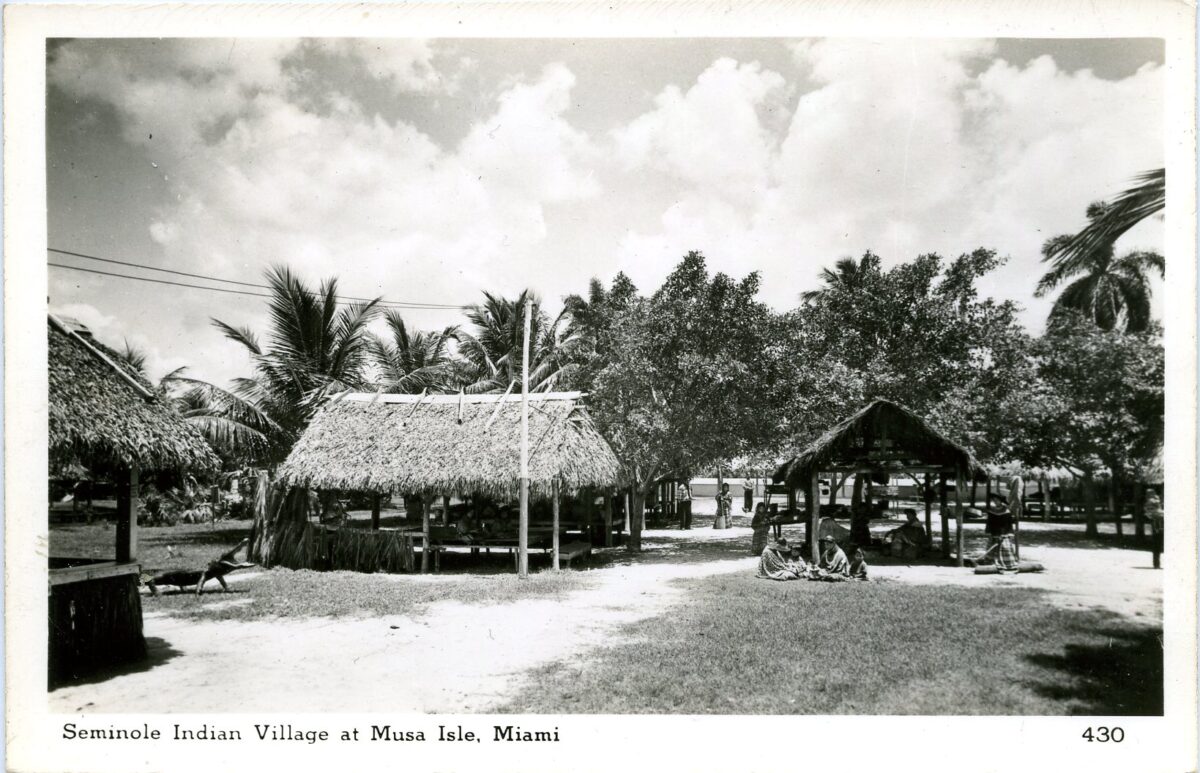

2000.30.7, ATTK Museum

Above, you can see several chickees at Musa Isle Indian Village in Miami, FL in the 1930s. This image was reproduced as a postcard. Notice the densely thatched roofs and the open sides. This would have allowed Seminoles to keep cool in the heat of the South Florida summer. The cabbage palm thatching is also waterproof, protecting people from rain.

In our featured image for this week, there is a postcard of another view of Musa Isle circa the 1930s. In this image, you can see a number of Seminole men and women, as well as a stuffed alligator to the left.

Materials and Tools

Typically, traditional chickees are constructed with two main components: a cypress log frame and cabbage palm thatched roof. More modern chickees fold in additional building materials due to availability and cost, like pressure-treated pine. Modern chickees may also augment traditional construction by adding cement floors or electricity. Modern chickees are constructed using nails, which are now readily available. In the past, the posts would have been notched or tied together, with the cabbage palm thatching tied down. Availability of materials is also a consideration, as “Cypress trees…are abundant in the swampy lands of the Big Cypress reservation, but are less common around the Brighton reservation” (Dilley 18). Thus, you are more likely to find chickees where the frame is built without cypress on the Brighton Reservation, due to availability and environmental constraints.

Cypress is a highly prized building material, with dwindling populations that require sustainable harvesting. Traditional practices are sustainable, and Seminoles “respect the land and know not to over harvest certain areas” (Dilley 23). Outside the reservations, Seminole and Miccosukee tribal members can also harvest cypress and other chickee building materials in Big Cypress National Preserve (BCNP), due to their customary use rights. There is also consideration when harvesting the cabbage palm leaves, where only some leaves are harvested from a tree at a time. This ensures the cabbage palm is not damaged, and the fronds grow back within a year (Dilley 25). The practice also helps regulate the cabbage palm population.

As chickee building has modernized, so have the tools used to construct these structures. Now, chickee builders have 4×4 vehicles to haul materials out of the swamp, chainsaws, pressure washers, post-hole diggers, and other modern conveniences. Prior to this modern area, builders would only use basic tools like machetes, axes, and shovels.

Construction

A chickee “is the open-sided, thatched-roofed Seminole dwelling made from palmetto and cypress trees” (Dilley 10). While they may seem like merely structures, chickees themselves represent a culture of artisanship and learning passed down for generations. In its most basic form, chickee frames are constructed with four upright ‘legs’ that support the roof and thatching. The larger the structure, the more uprights a builder would need to utilize. In the past, these uprights would have been relatively thin, as chickees were considered temporary structures. Seminole builders can construct a chickee in a matter of days, making them efficient, cost-effective structures. Additionally, they are waterproof and cooling in the humid Florida heat.

The cost of harvesting and processing a larger cypress log is greater than that of a thinner one, even if the larger logs are sturdier. Chickee builders would have also harvested these materials without the aid of modern tools, like chainsaws. Modern chickees tend to have a larger variety of material sizes due to the use of more modern tools, and since the structures no longer need to be so temporary (Dilley 20).

Thatching

Chickee builders sink cypress logs deep into the ground for stability in Florida’s sandy soil, and then construct the frame. What follows is the cabbage palm thatching, which is where a builder’s artistry can shine. There is a lot of intention, generational learning, and skill that goes into chickee building. In particular, “thatching techniques are often passed down from generation to generation, a practice that helps build family ties and promotes community togetherness and bonding” (Dilley 28).

The thatching determines if the roof will leak or not, with tightly thatched leaves giving the chickee a watertight roof. Most chickee roofs last five to seven years before they need to be rethatched, although a skilled builder can construct one that lasts much longer (Dilley 32). Some builders thatch the roofs in only one direction, and others in a zigzag pattern. The fronds go in opposite directions in alternating rows to ensure the life of the roof.

Chickees on different reservations may have different needs, which become reflected in their construction styles. For example, chickees on Big Cypress may have a steeper roof. Former Chairman James E. Billie noted that the steeper pitch (as much as a 45 degree angle, compared to the 26.57 degree angle found on Brighton), allowed those structures to shed rain more easily, important in the much wetter Big Cypress area (Dilley 37).

Chickee Roof, Interior, via semtribe.com. Notice the tightly thatched palm.

A house by any other name…

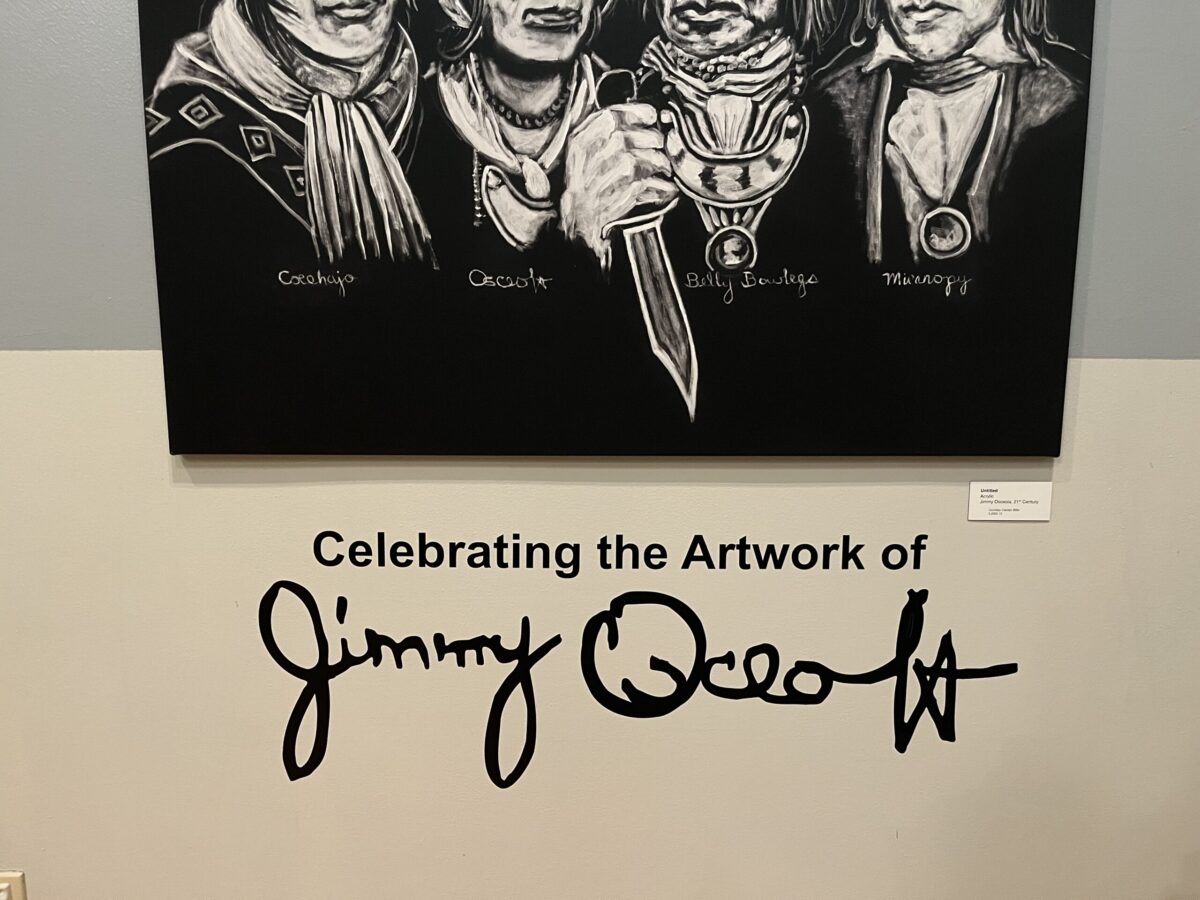

Even in South Florida, many people do not recognize the differences between chickees and Polynesian style tiki-huts, which became popular in the 1950s and 60s. Both are found in South Florida, where the tropical weather and easy-breezy island lifestyle make them an ideal choice. But, chickees are distinct in their cultural significance, construction style, and materials. It is no mistake that in the Art of Seminole Crafts, which is on display now at the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum, you step into the exhibit space under the fronds of a chickee’s thatched roof. Modern chickees are prevalent throughout the reservations, including on the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum’s Campus on Big Cypress.

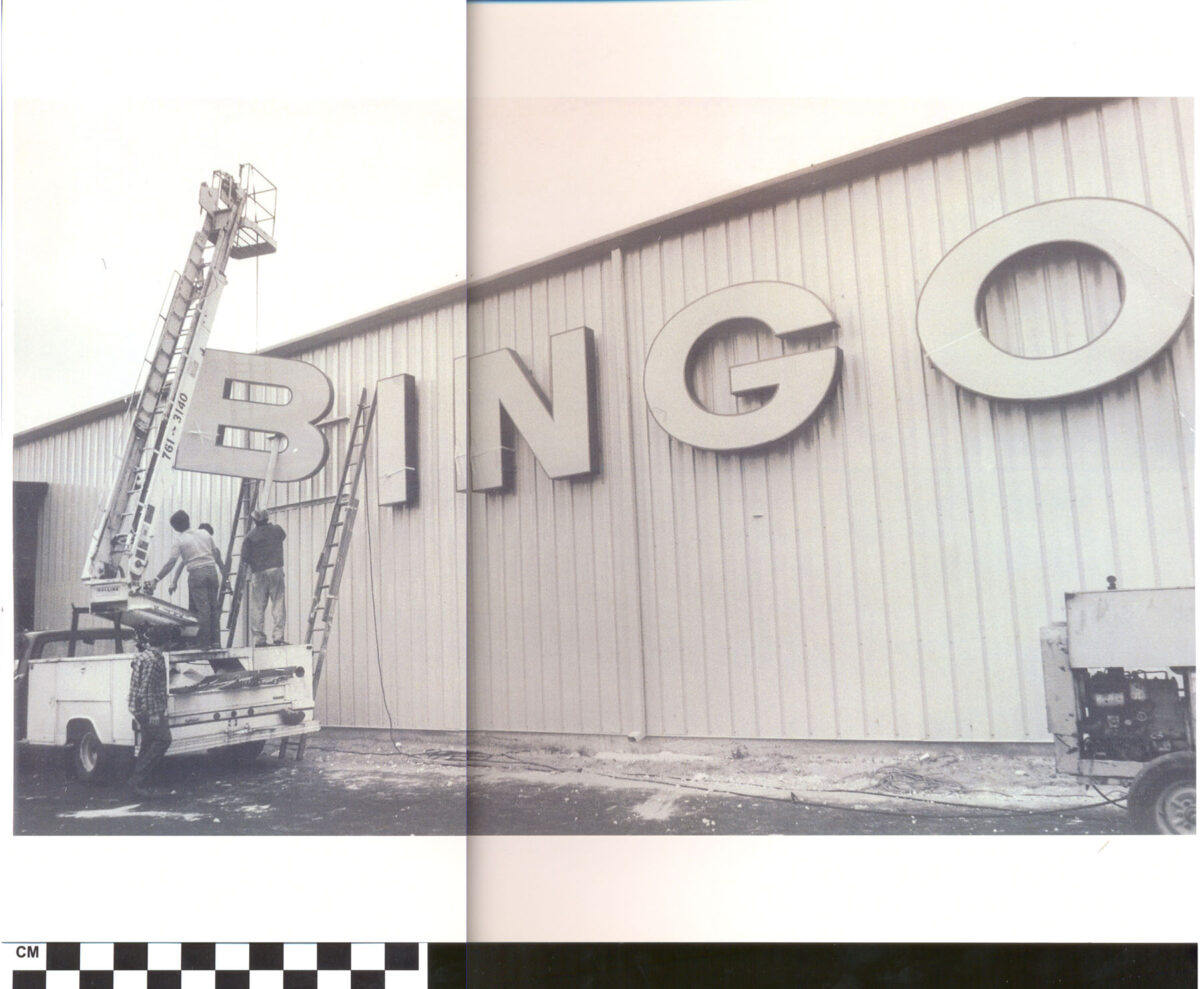

Chickees have been staple structures in Seminole craft villages from the 1920s onward through today. Chickees are so recognizably Seminole, Seminole artisans constructed them for traveling exhibition shows in the 20s and 30s, as well as popular structures at tourist camps like Musa Isle (West 76). These structures are protected under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, which focuses on fraudulent representation and marketing of native goods in the United States. Specifically, it means that chickees can’t be marketed as chickees unless constructed by a Seminole or Miccosukee tribal member.

In 2005, long-time chickee builder and former Chairman James E. Billie said “A lot of people try, but only a Seminole Indian can build chickees correctly…” (Dilley 13). Chickee building is big business, with stiff competition. As they became increasingly popular in the mid 1900s, “chickee building became one of the more lucrative ways to make money [in the 1950s]. It also allowed Seminoles to utilize their skills and showcase their culture while helping South Floridians live out their dreams of having a piece of tropical paradise” (Dilley 11).

Adaptation to an inhospitable world

Chickees came about as an architectural style through a need for a fast, disposable, and efficient shelter. Prior to the 1800s, Seminole ancestors in North Florida built multi-story log-cabin type structures, with sleeping quarters in the second story. But, the coming centuries would require Seminole adaptation in several ways. President Jackson pushed the Indian Removal Act through Congress in 1830. What followed was the Seminole War period, where Seminoles retreated to the safety of the Everglades to evade U.S. troops. Seminoles adopted chickees en masse at this time, although as an architectural style they have been around much longer (Dilley 53). Seminoles needed fast, efficient shelters made from readily available materials. Cypress and cabbage palms are both prolific in the Everglades, and made ideal building materials. Seminoles could construct chickees in a few days, and abandon them if needed even more quickly.

Historians have not pinpointed the exact origin of chickees in time. Most likely, chickees as an architectural style have been used by Seminole ancestors for thousands of years. As time went on, the styles shifted and changed with their needs, and with influences from other cultures (Dilley 53). But, it is apparent they became a necessary and popular architectural style in the Seminole War period, and have persisted through today.

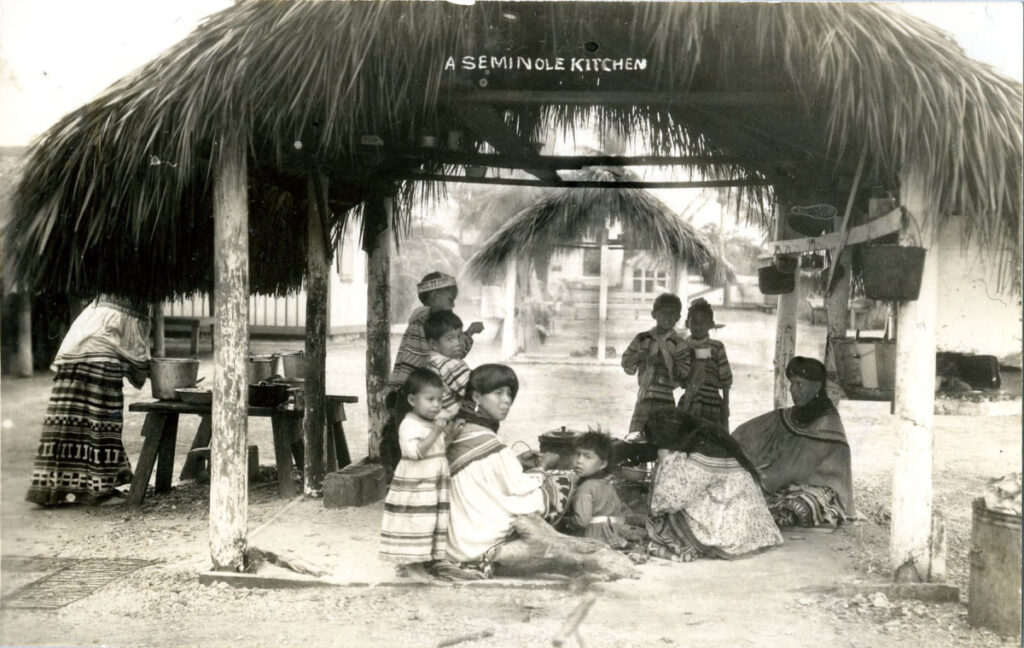

Chickees are at the heart of Seminole family camps, tight-knit matrilineal units that were the focus of Seminole life in the post-war period. A camp would have a collection of chickees divided by use: a cooking chickee in the center, surrounded by dining and sleeping chickees (Dilley 82). The cooking chickee would hold a “star fire”, constantly tended so it would not go out (Dilley 83-84). Below, you can see a cooking chickee, with the “star fire” at the center.

2001.27.3, ATTK Museum

A Way of Art

Now, chickee building is a highly respected form of Seminole artistry that utilized generations of knowledge, skill, and labor. O.B. Osceola Sr., a highly respected chickee builder who retired in 2018 after a lifetime of chickee building, stated in 1982 “It’s (a chickee) the coolest thing under the sun…You can’t stay under a canvas roof. But you get under a chickee, and you can fall asleep” (News-Press, 30 May 1982). Now, his son O.B. Osceola Jr. carries on his chickee building business, with the next generation thatching and constructing chickees in the same way as their parents.

Chickees represent something beyond just a structure, and come wrapped up with a vast amount of cultural knowledge and traditional practices. “It’s not just a shelter,” [Tina Osceola, O.B. Osceola’s daughter] said, “It’s something that blends so well within the natural environment. It’s something that people are taught all their lives to do – how to fold the leaves and create something that’s not going to leak” (News-Press, 08 Apr 2018). Master chickee builders like Bobby Henry, O.B. Osceola, James E. Billie, and others carry with them generations of knowledge, reflected in those cypress frames and cabbage palm thatched roofs. These efficient, seemingly simple structures represent Seminole resilience, a relationship with the surrounding environment, and a dedication to generational learning that transcends the raw materials.

Would you like to see some chickees? Artisans have constructed several modern chickees on the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Campus. They are located in the parking lot event space, just behind the Museum itself, in the Ceremonial Grounds, the Village, and the Hunting Camp. We encourage you to stop by!

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

Dilley, Carrie. Thatched Roofs and Open Sides; The Architecture of Chickees and Their Changing Role in Seminole Society. 2018. University of Florida Press. Digital.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting to Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.

Patricia Alberson

An awesome rich history of our state.I live in Jacksonville Fl and use to attend the powwow at Osceola Cox reservation.