Dear Friend: The Spectacular Photos of W. Stanley Hanson

Welcome back to the latest installment in our Seminole Snapshots series! In this series, we look at the impact of photography in preserving and sharing the Seminole story. This week, we look at an utterly unique collection, gathered over the lifetime of W. Stanley Hanson Sr. and his family.

Due to Hanson’s close relationship with the Seminoles and Miccosukee of the area, they are a predominant feature in the Collection. This close relationship is incredibly apparent in the photographs, which are unique in their candid, familiar tone. Often, those in the images are smiling, laughing, and engaging with Hanson. These snapshots are a far cry from the stiff, invasive, and almost forced nature of white photography of Seminoles at the time.

The Seminole Snapshots series is intended to highlight positive, truthfully taken, and non-exploitative imagery of Seminole and Miccosukee people throughout history. But, we encourage you to remember that even with the best of intentions, individuals always carry with them biases. In particular, those within this time period that fought to “help” the Seminole and Miccosukee carried with them the baggage of a colonial and Western way of thinking. Hanson, and others within this series, are no different. Thus, while exploring W. Stanley Hanson Sr.’s life and images, those included here and in the linked archives, we encourage you to appreciate Hanson’s impact and the positivity of his cherished relationships, while still understanding the biases in his perspective.

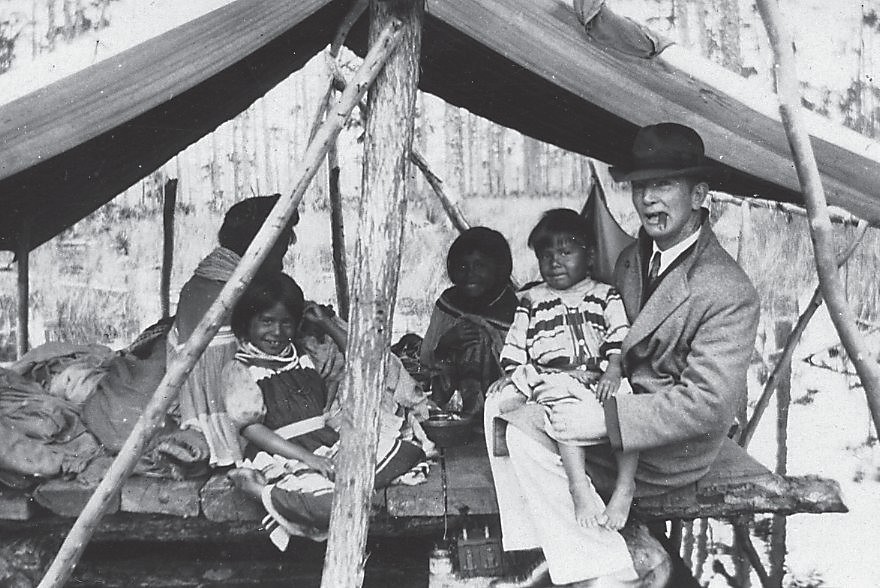

In our featured image you can see Hanson with Buck Cypress (left) and his sibling in a temporary camp in Immokalee in 1933. The attached note shares that the Cypress family left Big Cypress for Immokalee due to flooding, and Buck Cypress is suffering from hookworm. The Cypress family was in part asking Hanson to help them obtain hookworm medicine.

The Hanson Family Archives

While we will discuss the Hanson Collection throughout this post, it should be noted that the bulk of the items pertaining to the Hanson family are privately held by Woody Hanson. Woody Hanson, W. Stanley Hanson Sr.’s grandson, is a Fort Myers based historian that holds and manages the archives. It contains a variety of photographs, ephemera, and documentation from not only W. Stanley Hanson Sr.’s life, but the whole family.

In Cynthia Marie Mott’s 2011 thesis on the Hanson Family Archives, she notes that “It is the current Hanson family’s desire that their holdings be preserved and studied in the future. However, at this time, it is not their desire to hand the entire collection over to one university or museum.” (Mott 77)

Thus, throughout this post we will explore the parts of the Collection that are available for public consumption. We will particularly highlight the incredible connections W. Stanley Hanson Sr. fostered through his life. These connections and relationships are preserved through some of the images that remain. The images reveal a view into the lives of Seminole and Miccosukee people of that time that is rarely seen.

Below, you can see an image of W. Stanley Hanson Sr. holding the daughter of Johnny Cypress, possibly in his backyard in Fort Myers.

Via Florida Weekly, Courtesy of Woody Hanson

Stanley Hanson Sr.

Born in 1883 in Key West, FL, W. Stanley Hanson Sr. grew up and lived his entire life in Fort Myers, FL. His father, Dr. William Hanson, was a prominent Fort Myers doctor known for treating Seminoles before his death in 1911. Originally hailing from England, William and Julia Hanson were some of the first white settlers in Lee County. The Hansons moved to Fort Myers in 1884, when Stanley was only 6 months old.

W. Stanley Hanson Sr. would go on to live an incredibly varied life. Hanson worked as a tax collector, city councilman, was active in real estate, wrote articles syndicated in both local and national newspapers, and even worked as a nature guide. Within his works, many influential names of the time also pop up: Ernest F. Coe, the Edisons, Henry Ford, Ethel Cutler Freeman, and more.

At various points, he worked as an Indian Agent, based in Big Cypress. He became fluent in both Muscogee-Creek and Mikasuki and acted as a translator in some cases. Hanson was a fierce advocate for Seminole and Miccosukee rights.

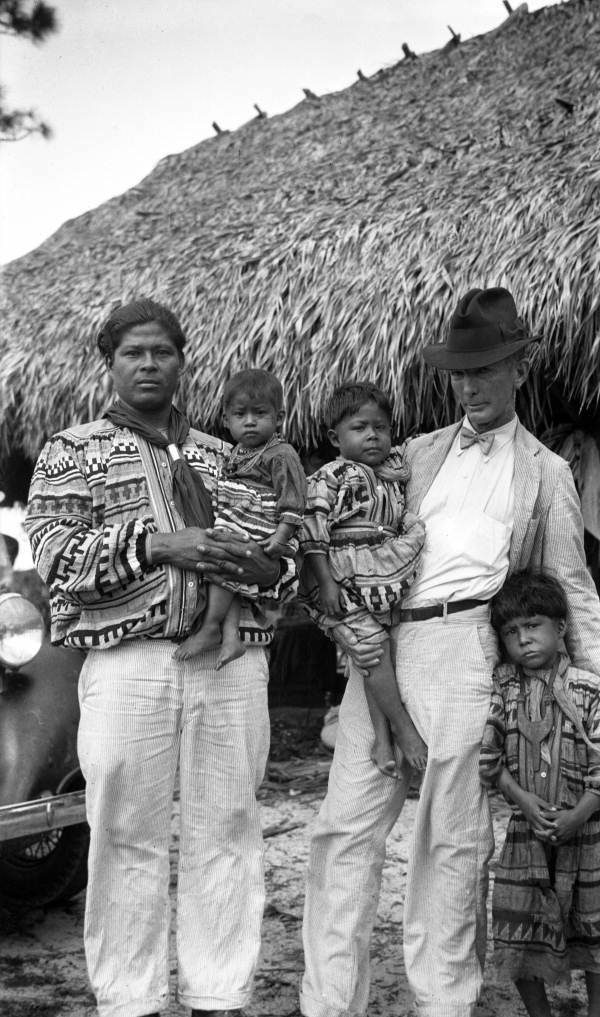

He defended them in court, advocated for their health and well-being, and also in some cases garnered economic support. Although he was not a doctor, Hanson was also well-known for helping Seminoles obtain medicine. In addition, there are even stories of him driving them in his own car to get healthcare. Hanson passed away in 1945 at the age of 61 in Fort Myers. Below, you can see Hanson sitting with a Seminole family on a raised platform.

Via Florida Weekly, Courtesy of Woody Hanson

The Trailblazers

An interesting point to consider is Hanson’s role in the “Trailblazers.” They were a collection of prominent men of the time pushing for the development of the Tamiami Trail. Hanson, and others of the group, left Fort Myers on April 4, 1923 on the first leg of their trek. They intended to cut a path through to Miami on the new trail (5 Apr 1945, News-Press). The journey took 23 days. Little Billy Conapatchee also joined the expedition. We featured his camp from 1910 in a previous Seminole Snapshots.

Hanson was dedicated to the health and well-being of the Seminole and Miccosukee of the area. He fiercely advocated for the preservation of their ways of life and rights. But, he also was involved, at least in this way, of furthering the development of the Tamiami Trail, which bisected their ancestral lands. Below, you can see an image of the Trailblazer expeditions.

2018.5.192, ATTK Museum

The Hanson Family

In addition to W. Stanley Hanson Sr.’s unparalleled collection, the Hanson family itself is an interesting facet of this story. In an interview with W. Stanley Hanson Jr. in 1975 for the University of Florida’s Oral History Program, the relationship between the William Hanson family and the Seminole/Miccosukee of the area is further explained. He states “During that period of my grandfather’s practice, the Indians took a liking to him, had confidence in him, came in and were treated by him….the children, came in with them and my father and the small children used to play together and they grew up knowing each other. That’s how he got established with them. As time when on, they had a trust and confidence in my father which was contrary to their natural suspicion of white man [sic] that they had had over the years” (Mott 18).

Stanley Hanson Jr. further shared that Dr. William Hanson regularly encouraged Seminoles who came to Fort Myers to trade and camp in their backyard and shared their food stores. This was a tradition that W. Stanley Hanson Sr. would soon continue, and during his time Seminole and Miccosukee friends of his would even build chickees in his back yard. In his personal notes, Wilson Cypress, John Cypress (below), Robert Osceola, and Frank Cypress are just some of the visitors that stand out.

In the same 1975 interview mentioned above, W. Stanley Hanson Jr. also remembers a conversation with his father and John Cypress about the thatching of one of the chickees in the backyard. He recalls “Johnny Cypress was thatching the one that he called his house or chickee in the backyard and my father made a comment to Johnny, he said, ‘Johnny, how come you put them on thicker on this one?’ Johnny looked at him with a kind of disgust and said, ‘This my house.’” (Mott 28)

Below, W. Stanley Hanson Sr. stands with the family of John Cypress (left). Cypress is holding his daughter Julia, and Hanson (right) is holding Buck Cypress, circa 1933. The accompanying note shares that they are all at a temporary camp in Immokalee, after flooding on Big Cypress forced them out.

State Archives of Florida

Relationship with Seminoles

We have talked throughout this post about Hanson’s long-time connections with numerous Seminole families. Some even named children named after him; Stanley Hanson Cypress, possible son of John Cypress, can be seen in the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Online Collection. But, in the Hanson Family Archives, these connections extend beyond images to written documentation and even letters between Hanson and some of his friends. These further emphasize the close connections Hanson had with his friends. In particular, Mott shares two correspondences that are particularly poignant in her thesis.

Letters With Friends

In the first, Richard Osceola writes Hanson to share that he is staying in Immokalee at Charley Cypress’ camp. Osceola and others moved from their camps on “acount [sic] of high water.” He writes for help, continuing that “Charley wants to know when you are going to Daytona Beach for he wonts [sic] to go with you so please let me hear from you at once. All the folk down here is out of something to eat and are in need bad.” He signs off “your friend as ever, Richard Osceola…P.S. Please come to see me as soon as you can….Johnnie Cypress broke the truck down” (Mott 25). These personal letters show not only familiarity, but also trust in Hanson and his dedication to help.

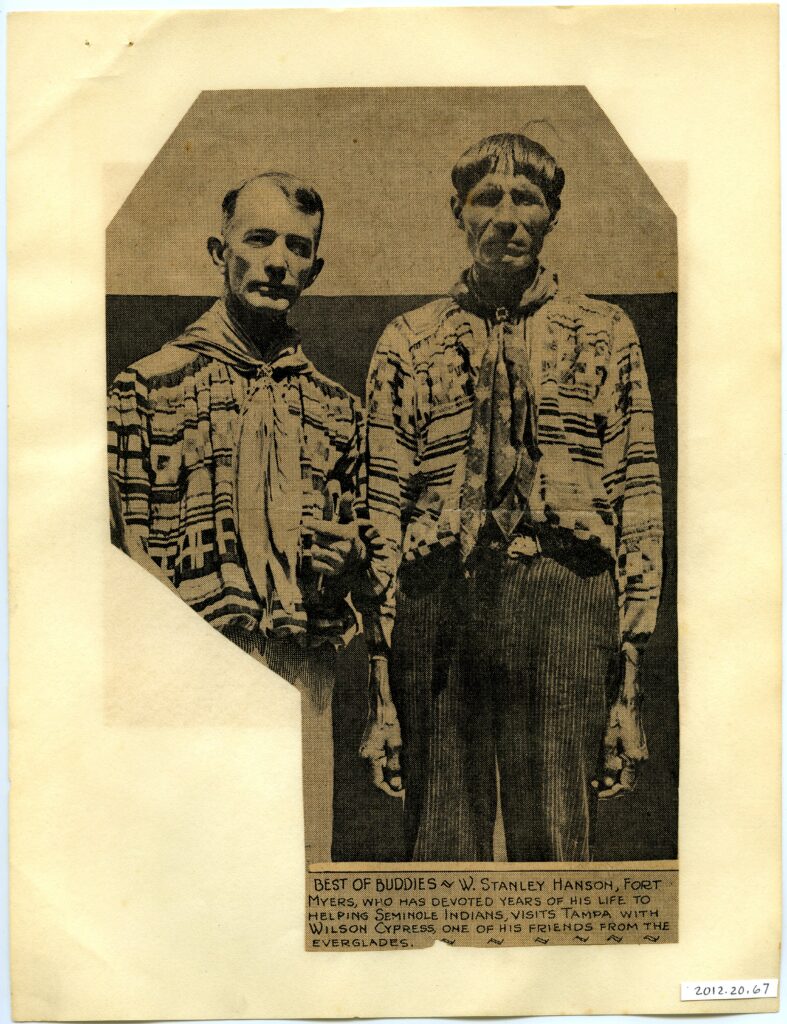

Hanson and Josie Billie also wrote each other often throughout the years. In his letters to Hanson, Billie addresses him as “W Stanley Hanson Dear Friend” (Mott 25). Josie Billie was an incredibly important and influential Seminole Medicine Man, and Hanson considered him one of his very best friends. W. Stanley Hanson Jr. spoke at Billie’s funeral in 1980, with him and his son Woody the only white men in attendance (12 Oct 2005 News-Press). Below, you can see a newspaper clipping showing W. Stanley Hanson Sr. and Wilson Cypress, another good friend.

2012.20.67, ATTK Museum

Parts of the Hanson Collection You Can Explore

Although, as we have noted above, the bulk of the collection is privately held, there is a selection of images that are available to peruse online. The most striking are those held by the National Anthropological Archives. We encourage you to explore the almost 300 images that are hosted in their online collection. These images showcase Hanson’s connection with a number of Seminole and Miccosukee families. They show Seminoles cooking, taking care of children, doing hair, canoeing, and just generally living their lives.

But, what makes them so special is the interaction between Hanson and those in his photographs. They’re smiling at him, laughing, and comfortable. When Hanson is in images at the time, he holds and cares for their children, joins their camps, and his own children play with theirs. Hanson is part of the images, even when he is not in them, because they are a visual representation of the relationships between them. You can explore these images at the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives here.

In addition, other images that are available for your perusal are those found through the Florida Memory Project and the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Collection. Most of those found on the Florida Memory Project are part of the State Board of Health Collection. In 1931, the Florida State Board of Health instituted a midwifery licensing program, with the intention to reduce infant mortality and promote child health.

The Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Hanson Collection

The Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum also received portion of this Collection in 2018, and some is featured here or available for online perusal. In 2022 the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Conservator Maria Dmitreva and Collections Manager Tara Backhouse wrote about the restoration of parts of the donated Collection.

They write that Hanson “devoted his life to medically treating Seminole citizens, as well as fighting for Seminole rights and facilitating communication between Seminole people and other local residents.” They continue that “These photographic prints from the last century tell us about lives and traditions, about outstanding leaders and tribal citizens, and also have a teaching mission. These photographs are antiques. Many have physical and chemical damage, and therefore need significant treatment work.” The Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum had treated 26 of the images by the time of publication.

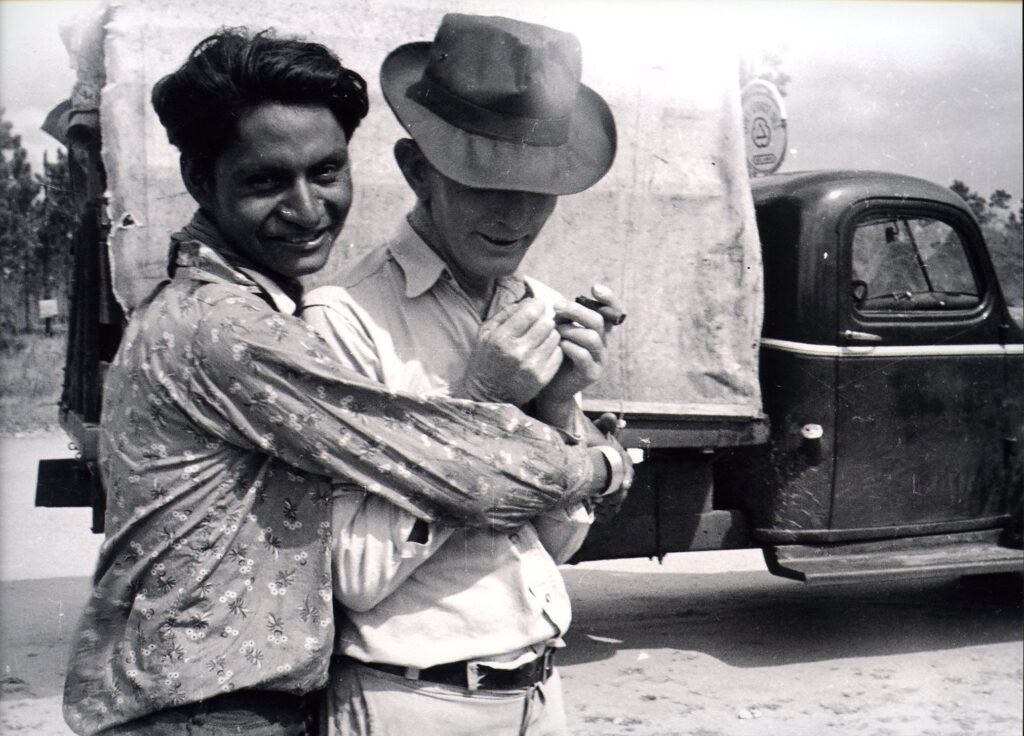

Hanson also appears in other Collections, like the image below which is part of the Ethel Cutler Freeman Collection. In it, you can see Henry Cypress and W. Stanley Hanson roughhousing in February of 1942.

2005.27.42, ATTK Museum

So, through these images, we encourage you to explore the life and impact of W. Stanley Hanson. Dedicated to his friends, he spent a lifetime advocating for Seminole rights, lifeways, and health during the turmoil of the early 20th century.

Interested in more Seminole Snapshots? Previously, we have looked at the works of Julian Dimock, Irvin M. Peithmann, William Boehmer, John Kunkel Small, and JJ Steinmetz.

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

Mott, Cynthia Marie, “The Hanson Family Archives of Fort Myers, Florida” (2011). USF St. Petersburg campus Master’s Theses (Graduate).https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/masterstheses/91

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Lakeland, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.