Seminole Snapshots: The Peithmann Collection

ISmile for the camera! Welcome to a brand-new series on the blog: Seminole Snapshots. In the past, we have explored how postcards were used to advertise and encourage Seminole tourism in the early 20th century. We have also looked at the Boehmer Collection, and how it has helped preserve and share precious Seminole history. So, this week, join us to look deeper at the impact of the Peithmann Collection, a collection of over a thousand photographs taken from the 1950s through the 1970s by Irvin M. Peithmann.

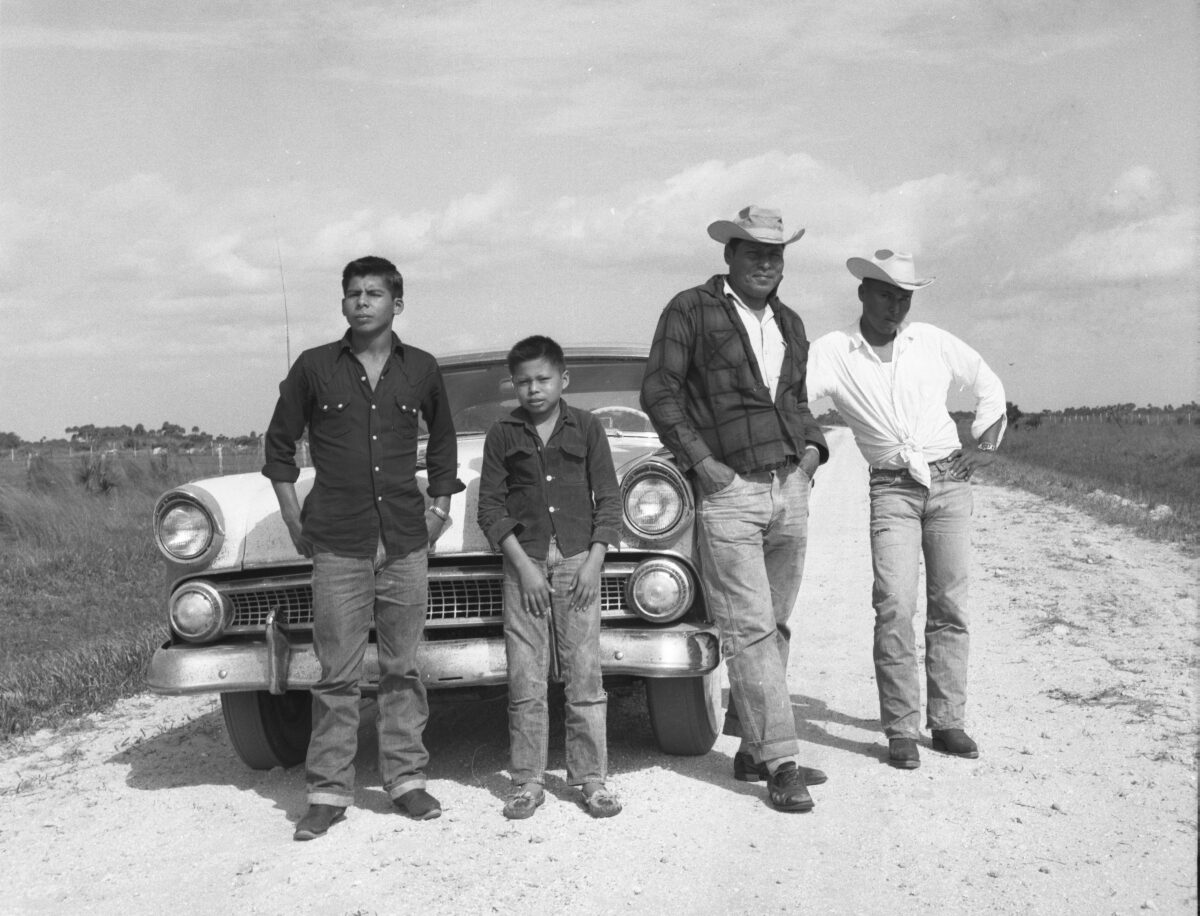

In our featured image this week, you can see Jimmie Osceola, Jol Johns, Andrew J. Bowers, and Harold Jones standing on a dirt road on the Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation in 1955. Most of Peithmann’s photographs thoughtfully documented Seminole life and people. Of course, some did include the author and photographer himself. Below, you can see Peithmann, left, sitting with the Charlie Cypress family, including his wife Lee Billie, in 1956.

Irvin Peithmann with Members of the Seminole Tribe, via the Randolph Society

Irvin M. Peithmann

Irvin M. Peithmann was born in 1904 in Washington County, Illinois. His father, Edward Peithmann, worked as a teamster for the Dawes Commission as a young man. The Commission was a congressional survey of the lands of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee-Creek, and Seminole nations. Consequently, it was responsible for stripping communal tribal lands, as it divided tribal lands into individual lots, and only afforded these lots to members on the Dawes roll. The US Government sold surplus territory to white settlers. Edward reflected later in life on the true impact of the commission, stating “The whole business there was so the white man could get a hold of [the land].” Irvin Peithmann’s father experiences, as well as his own budding interest in archaeology, would set him on a trajectory that would impact his entire life.

Despite his keen intelligence and curiosity, Irvin would only complete two years of high school. Soon, he began to work at Southern Illinois University, managing their farm in 1931. As a result, his interest in archaeology and anthropology would afford him the opportunity to work alongside others at SIU. He would make a number of important archaeological discoveries, including the Modoc Rock Shelter in 1951. He wrote his first book in 1955, tracing the history of native tribes in Southern Illinois.

Irvin would spend 1955-1957 with the Seminole Tribe of Florida, taking a sabbatical from SIU to move to St. Petersburg, FL. He wrote The Unconquered Seminole Indians in 1956. Irvin would write two more books, and continuously use his agency as an archaeologist and anthropologist to share the native perspective and stories. He would retire in 1973, and receive SIU’s highest honor, the Distinguished Service Award, in 1975 (06 Aug 1975, St. Lucie News Tribune). Peithmann passed in 1981.

The Unconquered Seminole Indians: Pictorial History of the Seminole Indians by Irvin M. Peithmann

Peithmann published The Unconquered Seminole Indians: Pictorial History of the Seminole Indians in December 1956 through The Great Outdoors Association. The Randolph Society, who honored Peithmann in 2020, noted that the book “aimed to present a new viewpoint, attempting to look at American history through a Seminole lens, rather than the other way around.” Peithmann himself would dedicate the book to “the Indians of North America who valiantly fought to keep their lands and hunting grounds.”

The Seminole story, a journalist writes in 1956, is “thoughtfully and graphically told by Irvin M. Peithmann. His attention to detail enables the reader to fully comprehend the Seminole and his way of life. His book…is copiously illustrated with more than a hundred photos, drawings, and maps…” (30 Dec 1956, Tampa Bay Times). Over a two-year period, Peithmann would document Seminole life in photographs, as well as trace their history in his book.

Peithmann’s Goal with the Book

“My motive in writing books is to tell nearly as possible what happened to the American Indian, from his own standpoint” Peithmann would state in 1965 (28 Mar 1965, Tampa Bay Times). Peithmann would note that his dedication to telling the Seminole story and trying to be compassionate to the history and tragedies of other North American tribes, made publishing the book a struggle. He said “this book, was turned down by 20 publishers over a five-year period. They didn’t think it would sell because of my statements of fact – it did not conform” (28 Mar 1965, Tampa Bay Times). During his research, Peithmann wanted to share the resilience of the Seminoles of Florida in the face of incredible injustices.

In his forward, Peithmann writes, “As Americans we should know the story of how the ancestors of the Seminoles were driven into the Everglades over one hundred years ago, a story of historic resistance against the white man and his power. The story of the Seminoles is an epic in American-Indian history” (Peithmann 5).

Peithmann in Florida, circa 1950s, Randolph Society

Peithmann’s Connection to the Seminole Tribe

Peithmann wanted to learn from and faithfully represent the Seminole Tribe, which shines through his work. In a 1965 Tampa Bay Times article, the author writes about Peithmann’s admiration for the Seminole Tribe. It reads “of the many tribes he knows, [Peithmann] admires the Florida Seminoles most. ‘considering the pressures, they have been under’” (Mar 28 1965, Tampa Bay Times). Peithmann was cognizant of the Seminole Tribe’s tumultuous history, which he detailed in the book listed above.

Seminoles invited Irvin into family camps, on cattle drives, and into their lives. He spoke fondly of his experiences, even waxing poetic about the food. “Fried homemade bread, nut-flavored razorback hog, deer, turkey, quail, cooked heart of palm cabbage, rice, oatmeal, corn meal, and a tremendous amount of lard and soda pop. Some of the finest meals I’ve ever had have been in the swamp” Peithmann noted (Mar 28 1965, Tampa Bay Times).

Peithmann/State Archives of Florida

Charlie Cypress and Lee Billie

In his time with the Seminole Tribe of Florida, Peithmann made numerous connections and relationships with Seminole Tribal members. Above, you can see Charlie Cypress, who is depicted in several Peithmann’s photos, whittling in a lawn chair on the Big Cypress Reservation. Charlie Cypress and his wife Lee Billie, shown and mentioned in the beginning of this article, were dedicated to helping maintain their culture and ways of life through the challenges of the 20th century.

Charlie Cypress was a master canoe carver and was prolifically photographed sharing Seminole crafting and traditions. In the February 2023 Seminole History Stories, the impact of the duo was explored. Lee and Charlie “did incredible work to preserve traditional Seminole culture during a time of intense change and transition. While they each have their own accomplishments that deserve to be celebrated, their partnership helped the continuation of traditional customs, values, and the expansion of the land on which the tribe continues to thrive today.”

Experiencing the Collection for Yourself

Here, you will find a selection of images from the Peithmann Collection. All these images are within the public domain, and available for perusal through the Florida Memory Project. Irvin donated his photographic collection to the State Library and Archives of Florida. From what we can see in his photographic and written record, Tribal members assisted and welcomed him during his time with them. Many assisted in his research and allowed him into their lives.

Below, you can see a group of four Seminole girls on a cattle roundup on the Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation in 1955. They wait for their coffee to boil over the fire. Scenes like this, that depict daily Seminole life on the reservation, are interspersed with nature shots, posed portraits, and special events. The vast majority of Irvin’s images are from the Brighton, Big Cypress, and Dania (now, Hollywood) Seminole Indian reservations.

Peithmann/ State Archives of Florida.

Often, incredibly influential Seminole elders or other notable figures show up in his images. These include Charlie Cypress (mentioned above), William McKinley Osceola, Reverend Billy Osceola, Josie Billie, and Charlie Micco. Below, you can see Charlie Micco repairing a saddle on the Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation. Peithmann snapped the image sometime in 1955. We have mentioned Micco in the past, who was instrumental in developing the Seminole cattle program on Brighton. Notably, Micco was the first cattle foreman of the Tribe, and his camp is now on the Tribal Register of Historic Places.

Peithmann/ State Archives of Florida

Related Images

Interestingly, several of Peithmann’s donated images included shots taken from photographer Bob Becker in the 1930s. Below, you can see an image included in the Peithmann Collection taken by Becker in 1930. In it, a dog looks on as a Seminole woman cooks food over a fire.

Becker/ State Archives of Florida

We have been able to share only a handful of the almost-thousand photograph collection that Peithmann donated here. Therefore, we encourage you to seek out and experience the collection for yourself! The wealth of images work to document Seminole life, experiences, and people from this not-too-distant past period in Seminole history. Thus, what makes Peithmann’s collection worthy of recognition is his commitment to meeting Seminoles as who and where they were, being welcomed into their lives to document the realities of Seminole reservation life at the time and working to faithfully represent them.

We encourage you to seek out Peithmann’s collection, as well as a handful of other photographic collections that try to thoughtfully share the Seminole story and experience. Check back in with us next month for another installment in the Seminole Snapshots series!

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

The Unconquered Seminole Indians: Pictorial History of the Seminole Indians. Irvin M. Peithmann. The Great Outdoors Association. 1956. Digital. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89069554335

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.