Florida’s Flora in Focus: the Photography of JK Small

Welcome to 2024! This week, join us for the latest installment of our Seminole Snapshots series, where we look at the impact of photography in preserving and sharing the Seminole story. Previously, we have looked at the works of Julian Dimock, Irvin M. Peithmann, and William Boehmer. This week, we will look at the images captured by renowned botanist John Kunkel Small.

Small made it part of his life’s work to document the flora of the Everglades. He also was a vocal advocate against the development that threatened this delicate ecosystem. During his travels, he documented not only precious plants, but also snapshots of Seminole life. Join us to explore the thousands of photographs, documents, and personal letters that are being preserved by the State Archives of Florida JK Small Collection.

In our featured image this week, you can see an image Small took of a wagonload of orchids, collected from Snake Hammock near Coot Bay, Flamingo, FL in 1916. Florida is home to 106 native orchid species.

John Kunkel Small

Most well-known for his research on the flora of the southeast and Florida in particular, John Kunkel Small was born in 1869 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. He studied botany at Franklin & Marshall College and received his doctorate from Columbia. In 1898, Small would take a position at the newly founded New York Botanical Garden. He would stay there until his death in 1938. Small’s first excursion to Florida was in 1901. He travelled to Florida “to see with his own eyes . . . the remarkable plants that others were sending him, to rediscover plants found long before. . . and to satisfy himself to what extent further exploration was needed. His eyes were opened” (Matthews 99).

He would continue to travel back and forth for the rest of his life, “to collect specimens, to study the natural history of the region, and to photograph natural landscapes, tropical plants, Seminoles and other local folk.” He would publish his dissertation “Flora of the Southeastern United States” in 1903. Small revised the book two more times: in 1913 and 1933. It remains to this day some of the best reference material for the flora in the Southeastern United States.

Charles Deering was a recurrent patron of Small’s expeditions. Deering believed that the devastation of the Everglades was imminent, and shared Small’s sense of urgency. In a letter from Deering to Small in 1915, Deering writes: “It is not impossible that the drainage of the Everglades will so change the climate as to injure and perhaps destroy much of the present vegetation. I am beginning to wonder if after I have [the Deering Estate] well planted with tropical things love’s labour will not be lost” (Matthews 105). With Deering’s funding, Small was able to take numerous trips around and through the Everglades. They shared vigorous correspondence that lasted until Deering’s death in 1927. The duo argued strongly for early Everglades conservation in Florida. Below, you can see JK Small’s two sons, George K. Small and John W. Small, on the eastern shore of Lake Okeechobee in 1913.

Early Florida Everglades Conservation

Small’s most famous publication, “From Eden to Sahara – Florida’s Tragedy,” outlined the devastation he was witnessing firsthand in Florida’s plant life and hammocks. In it, Small writes his predictions for the damage done to the Everglades. Although not all of it came true, many of his observations were strikingly accurate considering Small was making these observations in the early 20th century. He wanted his book to act as a warning, as he shared his observations over decades of exploring the Everglades.

Small and others such as Deering and Minnie Moore-Willson worked together to try to kickstart conservation efforts in Florida. She would write The Seminoles of Florida in 1896 and be instrumental in pushing for the state to designate reservation land for the Seminole people. Willson argued passionately for both conservation in Florida and the Seminole rights. Below, you can see Willson posing in 1880 with Billy Bowlegs III and Martha Tiger, the wife of Big Tom Tiger.

But, Small maintained hope that people were interested and engaged in stopping the destruction. In a letter from John Kunkel Small to Minnie Moore-Willson on January 21, 1929, Small writes that: “There is much activity now to get parts, at least, of the Everglades rescued from the vandals.” Small’s book was self-published but had wide reaching impact. By documenting the disappearance of Florida’s hammocks that he had seen in his 30 years exploring the Everglades, others began to recognize the importance of protecting this precious ecosystem. The book would in part be responsible for “sparking a movement for conservation of the wetlands that eventually resulted in the formation of Everglades National Park.”

Small’s Relationship with Seminoles

A botanist at heart, Small was also an explorer. The reality of his work in Florida was that he was documenting plants that were well known in the Indigenous community – but virtually unheard of outside of it. Not only that, but he tasked himself with documenting them before they disappeared. But, for Seminoles and Seminole ancestors these plants were all known, and intricate parts of a delicately balanced ecosystem.

For the Western world, Small was documenting them for the first time while simultaneously warning people of the high probability they would be fading away. Thus, during his time in Florida Small photographed on the fringes of Seminole daily life. Many Seminoles show up in his photos, such as the image below depicting Billy Bowlegs walking through his cornfield. We have talked about Billy Bowlegs before in a previous blog post.

Small documented not only Seminoles of the time, but also the remnants of Seminole ancestors that could be seen in the landscape. Progress at the time meant erasing, reducing, and engineering away both Florida’s natural beauty but also its original inhabitants. In his images, Small documented a number kitchen mounds, both small and large.

Below, you can see an image of a contoured live oak growing out of a kitchen midden comprised of oyster shells. Small captured the image at the Green Mound kitchen midden, in April 1922. Green Mound is one of the largest and best-preserved mounds in the state. It contains the refuse of centuries of occupation.

During his time around Green Mound, Small completed a botanical survey of the area, which revealed a number of rare plants and a collection of unique botanicals. Some of the plants he documented are still visible at the site including wild coffee, marlberry, and snowberry. Unfortunately, large portions of the mound were mined in 1933 for road construction. Today, the remaining portions of the mound are protected by Green Mound State Archaeological Site.

More of Small’s Images

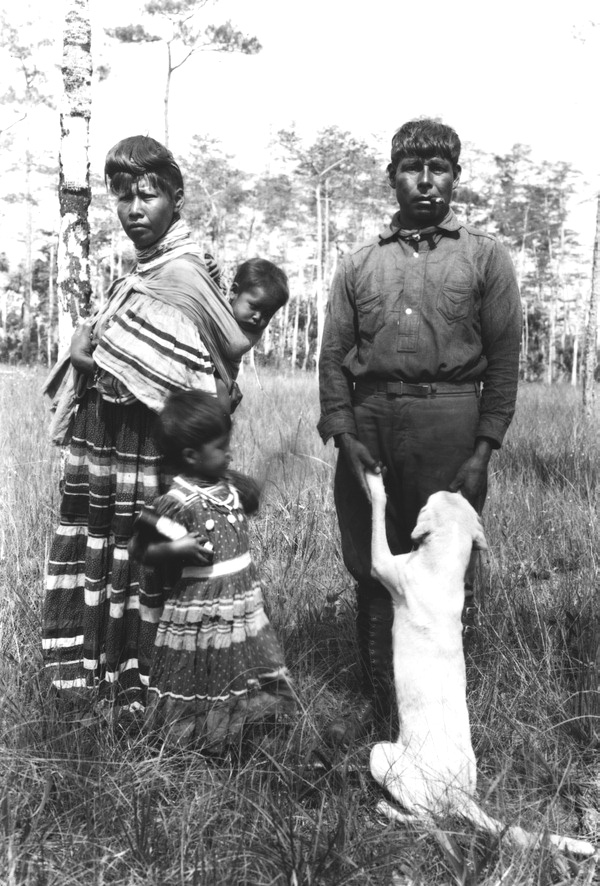

Many of Small’s images feature people that are recognizable Seminole leaders and figures of the time. Above, we were able to see Billy Bowlegs walking his cornfield. Below, you can see Josie Billie and family (and dog!) in the Big Cypress Swamp in April 1921. Billie was a cherished Seminole elder, medicine man, and spokesman for the Florida Seminoles. Born in 1887, he, along with Bowlegs, was a frequent face at the Florida Folk Festival. He lived on the Big Cypress Seminole Indian Reservation.

Below, you can see a quick snapshot of Doctor Tommy Jimmy, taken near Kendall, FL in 1916. Much like the Dimock images, some of Small’s photographs show a shift in Seminole fashion and clothing that happened in the early 20th century. The girls both wear banded skirts and capes, with no patchwork. Note as well their necklaces and hairstyles. We talked about the importance of Seminole fashion in a previous blog post.

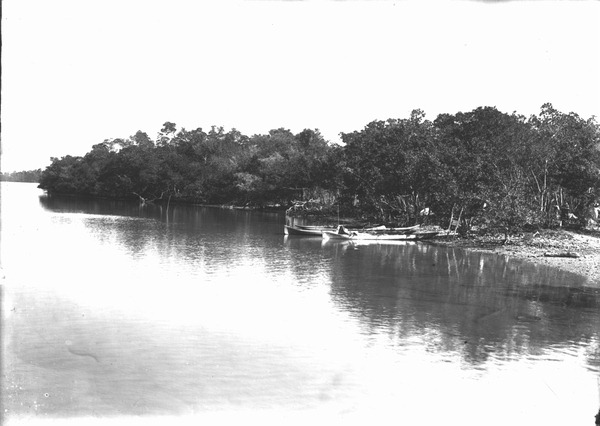

Additionally, since Small was exploring such ‘remote’ parts of the Everglades (at least from the Western perspective) there are a number of images of important locations to early 20th century Seminoles. Below, you can see canoes photographed on Chokoloskee Island in April 1916. Chokoloskee Island, which is part of the Ten Thousand Islands, has been an important location for Seminoles and Seminole ancestors for thousands of years. In the early 20th century, there was also an important trading post located on Chokoloskee, where many Seminoles would trade hides, furs, and plumes for purchased goods. Ted Smallwood’s Store at Chokoloskee served as a useful trade point, especially those who lived in the Ten Thousand Islands area.

Like the other collections we have discussed in our Seminole Snapshots series, we heartily encourage you to explore the collections on your own. A vast part of Small’s collection, more than 2,200 images, are available online through the State Archives of Florida. While many of these are Florida flora, other still are shots of daily Seminole life in the Everglades.

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

Matthews, Janet Snyder. Historical Documentation: The Charles Deering Estate at Cutler. May 1992. Metro-Dade County Parks and Recreation Department. UF Libraries. Digital. https://www.uflib.ufl.edu/spec/inhouse/Matthews_Deering_text.pdf

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Lakeland, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.