Seminole Snapshots: The “Camera-Man,” Julian Dimock

Say cheese! Welcome back to our Seminole Snapshots series, where we look at the impact of photography in preserving and sharing the Seminole story. Last time, we examined the impact of the Peithmann Collection, a collection of over a thousand photographs taken from the 1950s through the 1970s by Irvin M Peithmann.

This week, take a journey back in time with us to a wilder Florida. Between 1904 and 1913, Julian Dimock and his father A.W. Dimock travelled often through southwest Florida and documented their travels on film. From 1905 through 1910, the Dimocks amassed an over 2,000 image collection featuring Seminoles. This week, we will look at this priceless collection, how it came about, and how you can experience it for yourself.

In looking at these images, and the story surrounding the collection, we would also like to highlight why they are important, not only historically but on a personal level. In Hidden Seminoles, by Jerald T. Milanich and Nina Root, Tina Osceola (current Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Seminole Tribe of Florida) speaks explicitly about what these images mean to the Seminole Tribe.

Tina writes “These striking images document our people at a time following the Seminole Wars when they lived in the wetlands of the interior of south Florida. Their historical importance is beyond question. But to us, they have even greater value, for they are photographs of our ancestors, the people from whom we are descended. The people portrayed in Julian Dimock’s photos are our relatives.” (Hidden Seminoles vii)

Julian Dimock and A.W. Dimock

Julian Dimock and his father, A.W. Dimock, came to Florida to reinvent themselves as adventurers and explorers after decades of tumultuous financier careers in New York. A.W. Dimock had worked as a financier since he was 21 years old, and lost and gained multiple fortunes over the years. Julian Dimock got his interest in photography from his father, who later dubbed him the “camera-man.”

For their Florida trips, A.W. decided that he would be author and scribe to Julian’s photography, documenting their travels through magazine articles, essays, and images (Hidden Seminoles 13). “We canoed, camped, and photographed for years, Julian and I…. The illustrated magazine containing our work are published from New York to New Zealand.” A.W. wrote in his book Wall Street and the Wild (Hidden Seminoles 16). During their time in Florida, together the Dimocks wrote several books and nearly 80 magazine and newspaper articles.

Both Julian and A.W. Dimock were enchanted with the wilds of Florida. While in Florida, they predominantly travelled on their house-boat the Irene, navigating the bays and rivers with ease. On their travels, they nurtured a love for nature, and became avid sports and outdoorsmen. Below, you can see A.W. swimming with a manatee, an image taken by Julian in 1908 and included in their book Florida Enchantments published the same year.

In addition to those depicting Seminole life and culture, Julian took hundreds of images showing Florida wildlife. As a result, both became early conservationists, often writing articles about wildlife and environmental conservation. Their final trip to Florida would be in 1913. A.W. died in 1918, and Julian would not pick up a camera again after his death. He would later regret his role as photographer, saying “It ground the life out of me…. Self-respect vanished.” (Hidden Seminoles 7)

Florida Photographic Collection

The Collection

Julian Dimock donated over 4,000 glass negatives and photographs from his travels with his father to the American Museum of Natural History in 1920. The Museum subsequently catalogued, filed away, and forgot the images for over 50 years. In 1978, after restructuring placed the photographic archive under the purview of the library, Nina Root stumbled across the glass negatives while familiarizing herself with the collection (Hidden Seminoles 6). Root would explore the collection and write about Dimock’s work intermittently for the coming decades. Although we focus on the Florida Seminole images here, Julian Dimock took thousands of images throughout the South, Canada, and other locations as well.

In 2007, Root contacted Jerald T. Milanich, anthropologist and archaeologist with the University of Florida, about the Florida Seminole images. Together, they scanned each glass negative and recreated the Dimocks’ timeline from 1905 through 1910. One special aspect of this collection is Julian Dimock’s personal catalogue of the images. This provided Milanich and Root much needed context. Thus, they were able to connect images, people, places, and times with relative ease. The result was Hidden Seminoles, a book detailing the images Dimock took of the Florida Seminoles. While exploring the collection, we encourage you to try and recognize people and places that we have mentioned previously on the blog and in Seminole and Florida history.

The Dimock’s Journeys and Relationship with Seminoles

Julian Dimock’s first images in the collection that depict Seminoles were taken in April 1905, at Storter’s. Storter’s was a trading post located at Everglade (now, Everglades City) in the Ten Thousand Islands. The ten images, which depict Jimmy Billy, Charley Tommy, Billy Roberts, and four other unidentified Seminole men, show them loading and unloading supplies at Storter’s dock. They wear a mix of Seminole traditional clothing and store-bought items like vests and hats (Hidden Seminoles 29).

These images were the first of Dimock’s to depict Seminoles, and likely the beginning of a burgeoning relationship between the two. Charley Tommy, who is in these first photos, would later “sometimes serve them as a guide and interpreter and also provided introductions to other Seminoles.” (Hidden Seminoles 29) From these first interactions, the Dimocks would soon venture further into the Everglades and photograph Seminoles in their camps.

This collection of imagery represents a transitional period in Seminole history, right at the turn of the 20th century. Florida was changing, and Seminoles were grappling with how, and if, they would change along with it. Milanich notes that Seminoles were rightfully distrustful of outsiders after the horrors of the Seminole War period.

But, the Dimocks did end up creating connections and forging relationships with several people. “They’d find Indian encampments, sometimes with the fires still warm, but the Seminoles were in hiding.” Milanich explains, “There were a few trading posts and eventually the way the Dimocks won the Seminole over was by taking pictures of some of them when they came to trade, then giving them prints.” The result is an unprecedented slice of Seminole life right at the turn of the 20th century, when Seminoles continued to separate themselves from white settlers in the interior of Florida.

Experiencing the Collection for Yourself

During his travels, Julian Dimock amassed thousands of images of South Florida; from wildlife, to people, places, and landscapes. Many of these images depicted Seminoles, including their camps, traditional dress, and daily activities. In this post, we are only sharing images that are either in the public domain or held by the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum. If you would like to experience the full collection, Dimock’s glass negatives are digitized by the American Museum of Natural History and available here.

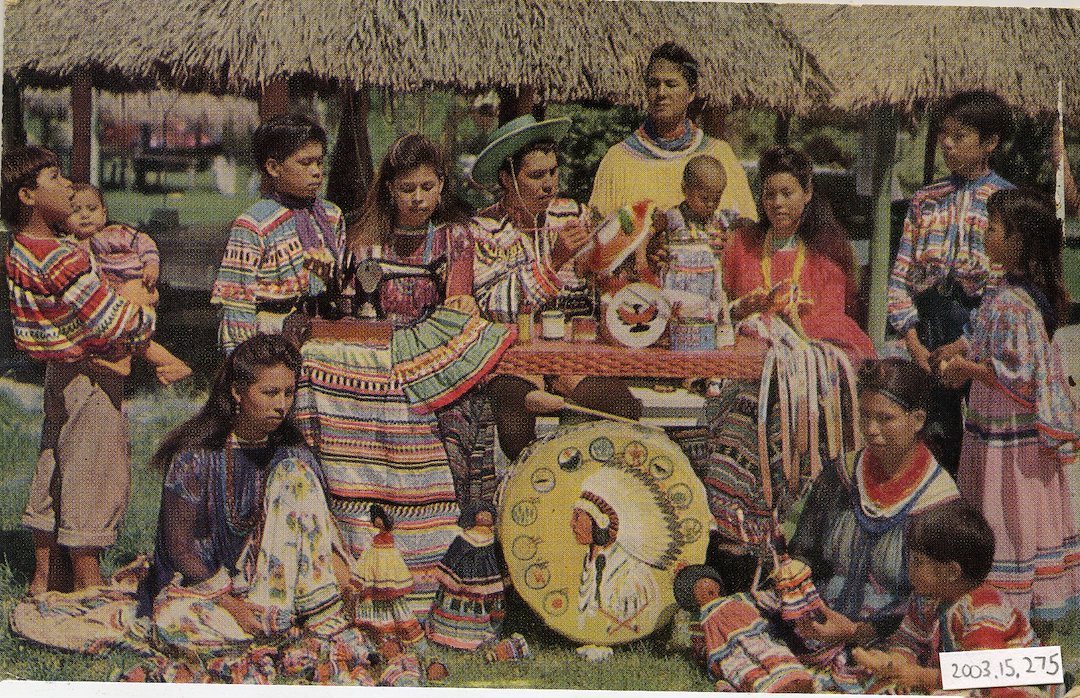

If you would like to learn more about the journey behind the collection, as well as see the images in a curated, yet comprehensive, manner we encourage you to explore both books listed below under the Additional Sources heading, written by Jerald T. Milanich and Nina Root. Through these expeditions, “Julian’s camera captured many aspects of Seminole Indian life: houses, canoe trails, village layouts, dress, crafts…. In a few of the 1910 photos we can see the beginnings of Seminole Indian decorative patchwork sewn on men’s shirts and women’s blouses and skirts.” (Hidden Seminoles 23) Some of these can be seen below in this small preview of the Collection.

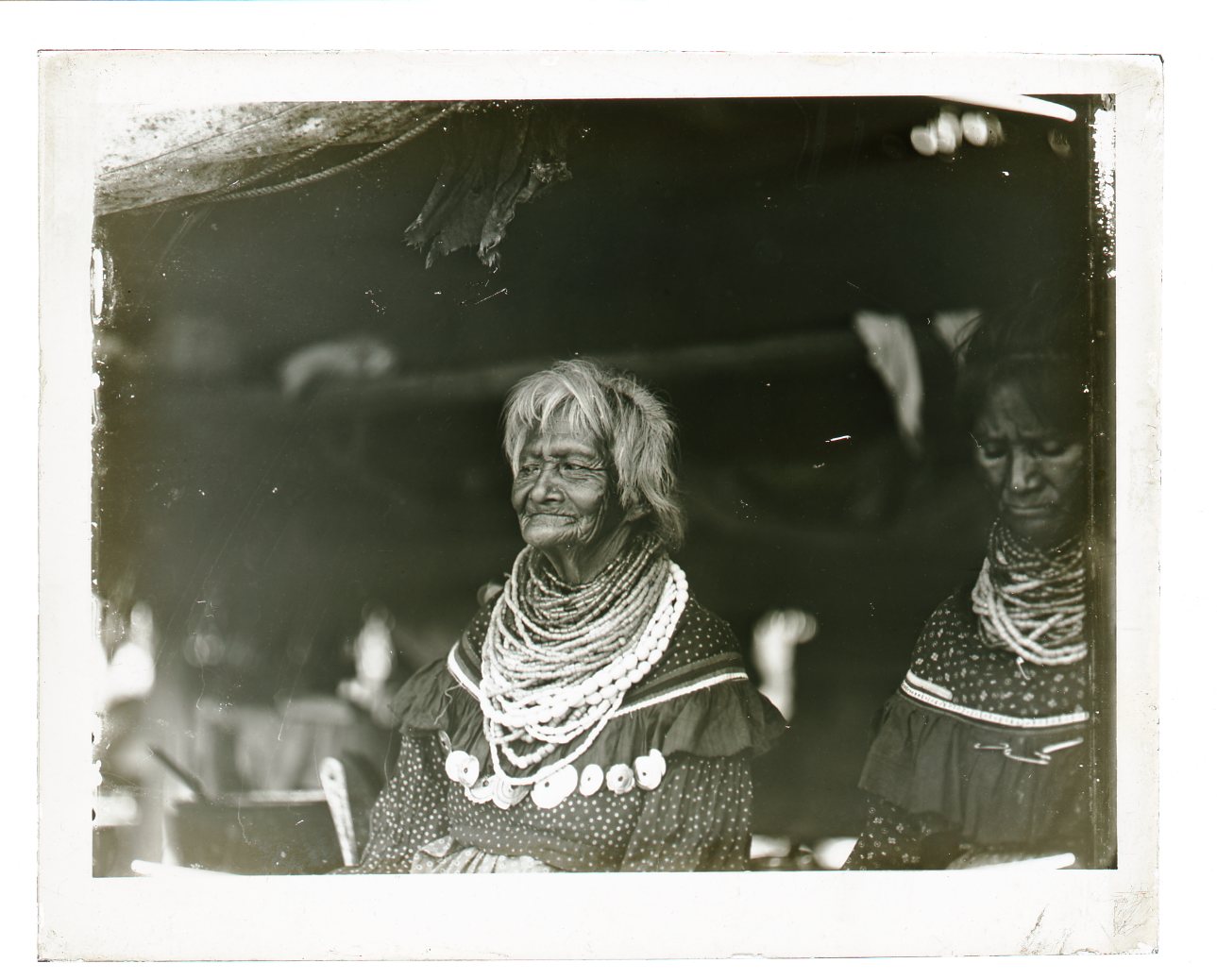

In our featured image, you can see the widow of Tigertail (left), with her daughter, wife of Little Tiger (right), at Miami John Tiger’s camp circa 1910. They both are wearing traditional clothing, including vast amounts of beaded necklaces. These include hammered silver coin brooches, as well as large white beads made from Busycon shells (Hidden Seminoles 171). You may remember this image from a previous exhibit! It was featured last December in the Art of Seminole Crafts exhibit at the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum.

Through Julian’s Lens

2012.3.34, ATTK Museum

Above, you can see Charley Tommy poling a canoe in 1907. Visible behind him is a canoe trail leading to Tommy Osceola’s second camp. On this trip, the Dimocks had intended to explore more of the interior of the Everglades and the Big Cypress Swamp, after a successful crossing in 1906. Ultimately their venture across the peninsula failed to reach Miami. In one of his articles about the failed expedition, A.W. notes that “We began the trip in a canoe but ended it in an ox-cart.” (Hidden Seminoles 37)

Charley Tommy acted as guide, and initially warned the Dimocks that the journey most likely would not succeed. Tommy warned that the proposed route was too dry for their crossing, and the group would end up slogging through the low water dragging their canoes. They ended this expedition at Brown’s Landing, another trading post, with Charley Tommy leaving for home and the Dimocks painfully making their way back to Punta Rassa by ox-cart (Hidden Seminoles 46). Julian would not make another trek into the interior until 1910.

took 2012.3.1, ATTK Museum

Taken August 21, 1910, this slide shows Little Billy Conapatchie’s (also known as Billy Cornpatch) camp. Dimock took these images as part of an expedition with Alanson Skinner for the American Museum of Natural History. While visiting Conapatchie’s camp, Dimock took several images following the camp’s daily life. These include processing meat, grinding corn with a mortar and pestle, sifting cornmeal, and poling canoes. There are also staged images. Several adults wear full traditional regalia. This includes Little Billy Conapatchie posing with feathered turban, beaded sashes, and a rifle. While grinding corn, Little Billy Conapatchie’s wife wears dozens of beaded necklaces and a long skirt and cape.

More Images from the Collection

In the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collections, they also have several of Dimock’s images that have been hand-tinted and commercially produced. An artist would have painstakingly added the color by hand. Then, the image was reproduced for postcards and other material goods. Below, you can see a hand-tinted slide of one of Dimock’s photographs, taken in 1910. It shows Wilson Cypress poling a canoe outside of Godden’s Landing, which had previously been known as Brown’s Landing. This image was also taken as part of Alanson Skinner’s 1910 expedition for the American Museum of Natural History, on which Dimock acted as photographer.

2012.3.25, ATTK Museum

We encourage you to explore Dimock’s Collection, which is available online through the American Museum of Natural History. Interested in other installations from our Seminole Snapshots series? Check out our previous blog posts on the Peithmann Collection and the Boehmer Collection. Additionally, look out for more posts on photographic collections featuring Seminoles and Seminole history!

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

Milanich, Jerald T., and Nina Root. Hidden Seminoles: Julian Dimock’s Historic Florida Photographs. University Press of Florida. 2011.

Milanich, Jerald T., Nina Root. Enchantments: Julian Dimock’s Photographs of Southwest Florida. University Press of Florida. 2013.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.