Wait…Seminole Totem Poles?

In the last few months, we have touched on several important Seminole crafts. From sweetgrass baskets, Seminole dolls, wood carvings, and patchwork, each holds a special place in Seminole history and culture. But, did you know that in the 1920s totem poles made their way into Seminole crafts? Although not explicitly rooted in Seminole tradition, totem poles have become a special part of Seminole culture and history over the last century. This week, join us as we look at Seminole totem poles, their complicated history, and how they became a shared tradition.

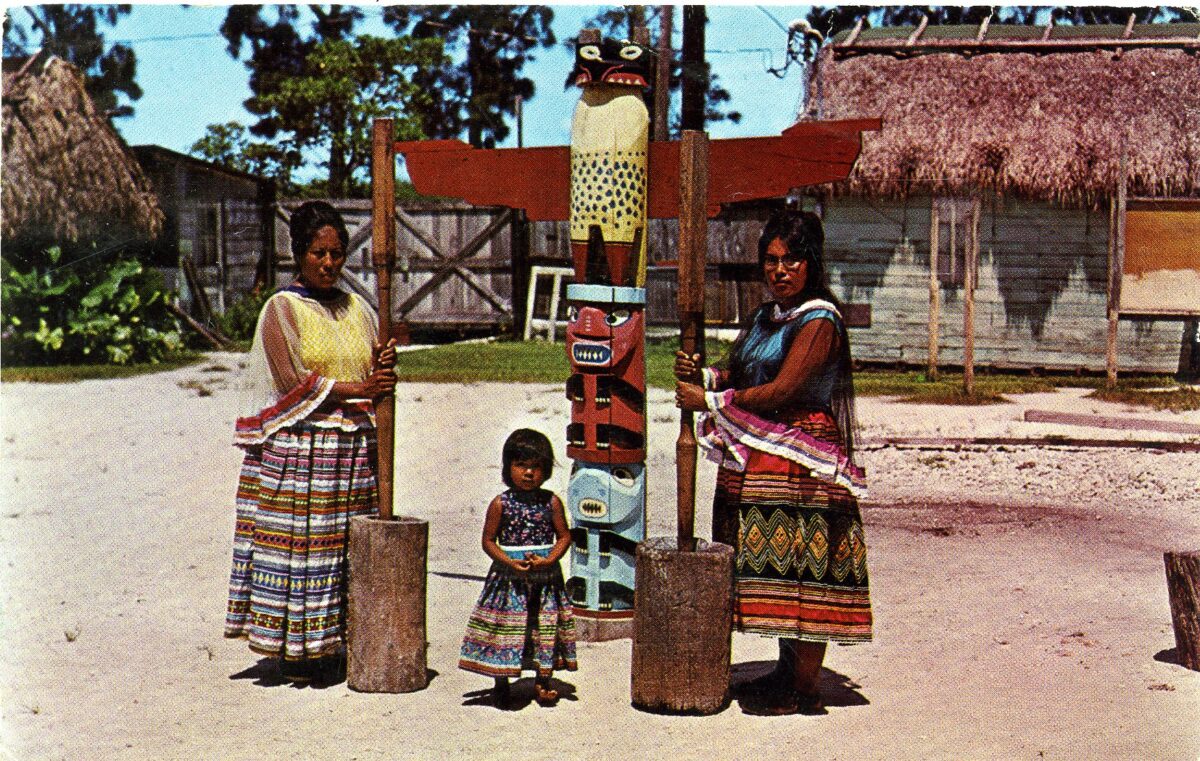

In our featured photo this week (ATTK 2003.15.105), Peggy Osceola, Marla Poole, and Virginia Poole (L-R) stand grinding corn next to a totem pole at the Seminole Indian Village on Tamiami Trail. All three are wearing patchwork, and the older women are wearing capes. An original photo was turned into the color postcard you see here. To learn more about postcards and their impact in Seminole tourism, check out a previous blog post here!

1998.23.9, ATTK Museum

Totem Poles and Anti-Potlach Laws

When discussing totem poles in Seminole history, it is important to address the cultural origins of what we refer to as “totem poles.” Tribes from the Northwest Coast of the United States and Canada carved this style of monumental poles out of red cedar. According to an essay by Robin K. Wright, “The figures carved…generally represent ancestors and supernatural beings that were once encountered by the ancestors…who thereby acquired the right to represent them as crests, symbols of their identity, and records of their history.” They were deeply personal and important. In the late 1800s, most Northwest Coast tribes stopped carving monumental poles due to anti-potlach laws. New poles and masks were important parts of potlach ceremonies. But, potlatch ceremonies were outlawed in Canada in 1884 as a government form of cultural suppression.

Potlatches were held in secret until the ban was lifted in 1951. Wright notes “Ironically, it was during this same late nineteenth period when old poles were disappearing from Native villages and the people were not allowed to raise new ones, that totem poles became a powerful symbol of the Northwest Coast to outsiders, largely through the tourist industry…. At this time Native artists began to carve small model poles for sale as souvenirs to tourists.” This symbol made its way to Florida and the rest of the United States. Wright acknowledges that “In some cases, totem poles have been used as symbols of all North American Native peoples, and indeed, Cherokee, Ojibwa, and Seminole carvers have produced small model totem poles for sale all across North America, despite the fact that there was no ancient tradition for this art form among their people.”

Totem Poles at Seminole Tourist Villages

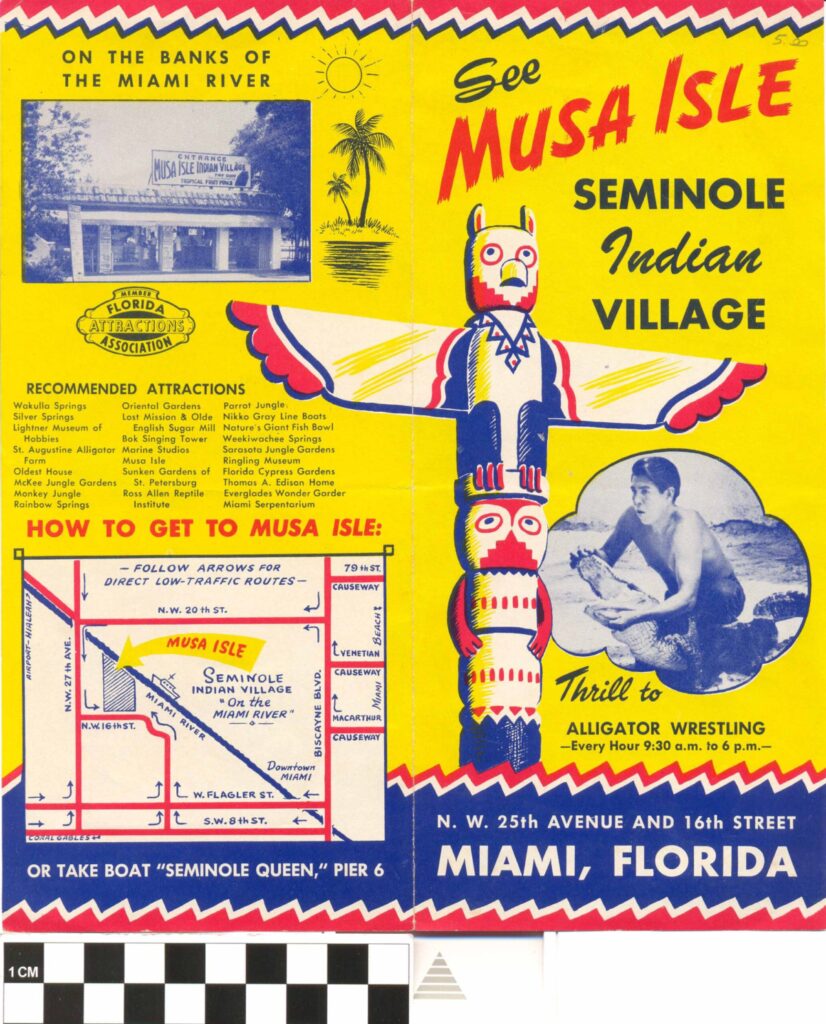

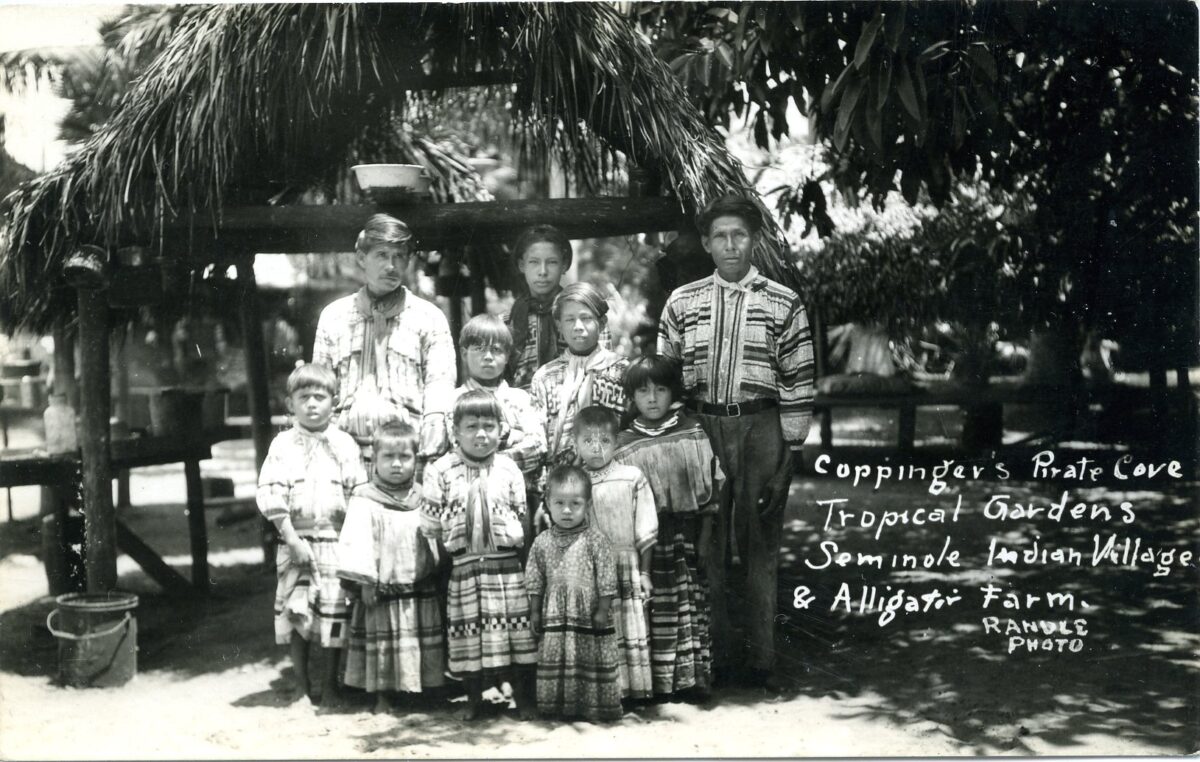

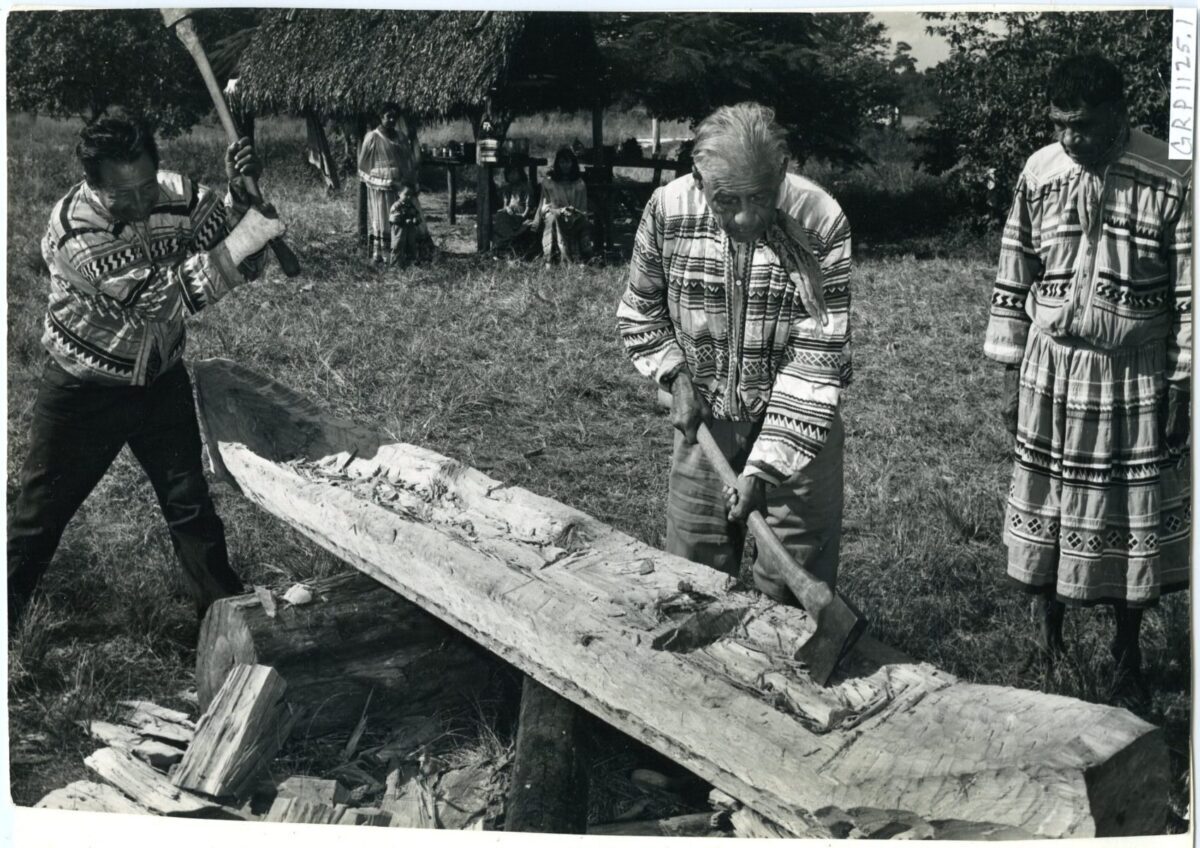

At some point in the 1920s, totem poles began to make their way into Seminole tourist camps and villages. Sonny Coppinger, the youngest Coppinger brother, recalled that Seminole men began to carve totem poles for Coppinger’s Pirate Cove Seminole Village around 1928 (West 124). Seminole carvers made them out of cypress wood. Musa Isle Seminole Village would soon follow this trend. By 1938, Musa Isle commissioned Frank Willie and several other craftsmen to make poles to decorate the front of the Seminole Village. Buffalo Tiger painted the poles. Then, they were set in cement along a rock wall at the entrance of the village (West 124). Artists also carved miniature totem poles to sell at both tourist attractions as souvenirs. Above, you can see a multi-page brochure advertising Musa Isle in the 1960s. Printed in red, blue, and yellow, it prominently features a totem pole on the cover.

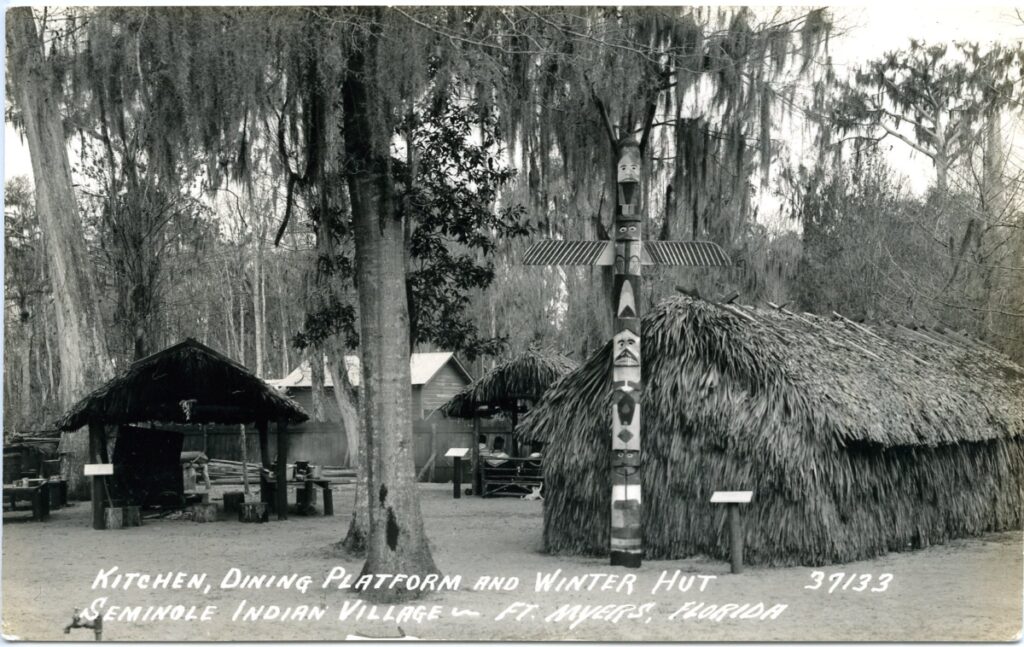

By the 1930s, bright, multi-colored totem poles were prolific across Florida Seminole and Miccosukee tourist camps and villages. Like the Pointing Man signs discussed in last week’s post, these totem poles were a bright marker directing tourists into the camp. Then, crafters sold would sell smaller, model poles alongside the other crafts. This would continue for decades, directing tourists to craft shops and camps. Below, a black and white Real Photo postcard shows a Seminole Indian Village in Fort Myers, FL. From around the 1950s, it shows three separate chickees with a large painted totem pole in the center, surrounded by trees. L.L. Cook Co. out of Milwaukee, WI printed this Real Photo postcard. It is a great example of how, over the course of a few decades, totem poles became an abundant part of Seminole tourism and culture.

2003.15.169, ATTK Museum

Deaconess Bedell

In 1933, Deaconess Harriet Bedell of the Glades Cross Mission in Everglades City, FL established a crafts cooperative for Seminole and Miccosukee artists (West 122). Bedell wanted to help them expand their crafts enterprises, and move away from the more heavily commercial offerings. She insisted on only well-established Seminole traditional crafts like patchwork, dolls, and baskets. Items like totem poles took influence from tribes in the Pacific Northwest and Canada, and Bedell deemed them inauthentic. She encouraged Seminoles “to develop an art of their own, not copying that of western Indians (West 123).” Bedell was extremely strict about what she sold at the Mission store. She even controlled what patchwork designs could be made and sold, limiting them to seven “traditional” designs. But, her influence was not without limits. Many Miami and Tamiami Trail villages continued to sell what Bedell deemed “inauthentic” art (West 123).

Bedell was a shrewd businesswoman, and her direction helped shape Seminole tourist crafts in many ways. She helped encourage the Seminole doll trade, as well as the continued support of Seminole baskets and patchwork. Her influence helped a large subset of Seminole and Miccosukee families survive crushing poverty. But, art, in this case Seminole art, is not an unchanging monolith as Bedell wanted to encourage. Art and culture adapt and change along with the people and times. Patchwork, one of the most important and iconic Seminole crafts, developed because of a series of political, economic, and cultural shifts. Change happens, and this is not untrue for Seminole art. At this point, Seminole totem poles have been a piece of Seminole history for almost a century, and deserve a nuanced and careful discussion.

But…how did they get there?

You may be thinking; why did Seminoles adopt a tradition that wasn’t theirs? And how did they come to Florida? While this may seem confusing, at its core items like totem poles weave another thread in the historic reality of Seminole resilience. The early 20th century was one filled with poverty, upheaval, and changes to the Everglades as Seminole and Miccosukee people had known it since creation. Tourism as an economic venture represents a critical adaptation. Seminole and Miccosukee people could make money to support their families, while not catering to the whims of government agents. Totem poles and other appropriated native art styles were what tourists expected, and sales helped solidify that economic independence. In places like the Miami attractions, other indigenous peoples would also visit the camps and share their art, which would then find its way into Seminole crafts (West 123).

In 2019, the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum’s Collections Manager Tara Backhouse wrote about the inclusion of art from other tribes in an article on the Museum blog and in the Seminole Tribune. Backhouse states that “Around the turn of the 19th century, Seminole people became involved in tourist attractions that featured their own cultural traditions packaged in a way that tourists would appreciate and pay for. In turn, people working in those camps were exposed to totem poles and other forms of art that weren’t traditionally Seminole. So, they adapted and took on some of those traditions.” These adopted art styles became popular throughout Florida, and helped foster economic survival.

Becoming a Shared Tradition

While the roots of Seminole totem poles lay in tourism, they are part of the Seminole story. Now, the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum works to celebrate, preserve, and interpret Seminole History and Culture. This includes Seminole totem poles, and several them are present in the Museum Collection. Below are two poles in the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collection. In the front, you can see a colorful totem pole by Mark Billie carved out of cypress. Billie painted it in bright colors including yellow, red, green, and white. The pole depicts panther, bear, and otter figures–three of the eight Seminole clans. Another pole rests behind it. Bobby Henry carved it for the first pow-wow held at the Coo-Taun Cho-Bee Village in Tampa. The Village displayed it there for a time. Henry left the pole depicting human and owl figures unpainted.

1991.10.1, ATTK Museum.

In the article linked above, Backhouse also addresses the idea of ‘authenticity’ in Seminole history and art. Totem poles are a part of Seminole history, and in many ways linked to the same sort of adaptability and resilience that made them the Unconquered Seminoles. Backhouse notes “Some people say that things like totem poles need to be thought of differently, that they are not Seminole, because they originated on the west coast of North America. But in my opinion, that’s a very narrow viewpoint. History doesn’t stop, and culture changes constantly. And why should Seminole artists have been exclusionary in the early 20th century, when they saw totem poles and admired them? After all, new skills helped Seminole people make money. Anything that helped Seminole people gain economic independence after a devastating century needs to be appreciated. For these reasons, we have totem poles in our collection.”

For this article, we accessed the book below digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting to Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.

Gabriel

Wouldn’t you consider this cultural appropriation? Sure, the Seminole culture might not have been dominant over tribes who originally had totem poles as part of their culture, but you stated that Seminole tribes appropriated an aspect of a culture purely for personal financial gain. Why is it okay for Seminole People to do what you would call a wrong act an somebody else?

Deanna Butler

Gabriel, thank you so much for your thoughtful comment! Seminole totem poles were predominantly made in the early 20th century, when conversations about cultural appropriation, and what is appropriate to take, use, and borrow were not common place. We try and view stuff like this in the appropriate historical lens. You are correct in that this is a tricky issue and it is difficult to answer your question. Our understanding of appropriation, culture, and how it changes has shifted over the last 100 years. As it is, it is a part of Seminole history and it is important to talk about these issues and their long term implications.