Seminole Dugout Canoes

In the past, we have focused a lot on Seminole crafting and making traditions. Often, we have looked closely at crafts and goods sold to tourists at camps and villages in the early 20th century, specifically patchwork, dolls, and sweetgrass baskets. An interesting and important feature of many of these crafts is that they were examples of functional beauty. Patchwork clothing was worn, baskets were used to hold food and goods, and dolls entertained. This week, we focus on another example of functional crafting: Seminole dugout canoes. Incredibly important to Seminoles prior to the 1900s, dugout canoes as a crafting tradition have waxed and waned with the shifting times. But recently dugout canoes have made a resurgence in Seminole making traditions. So, join us this week to look at the importance of Seminole dugout canoes and their role in Seminole history and tourism.

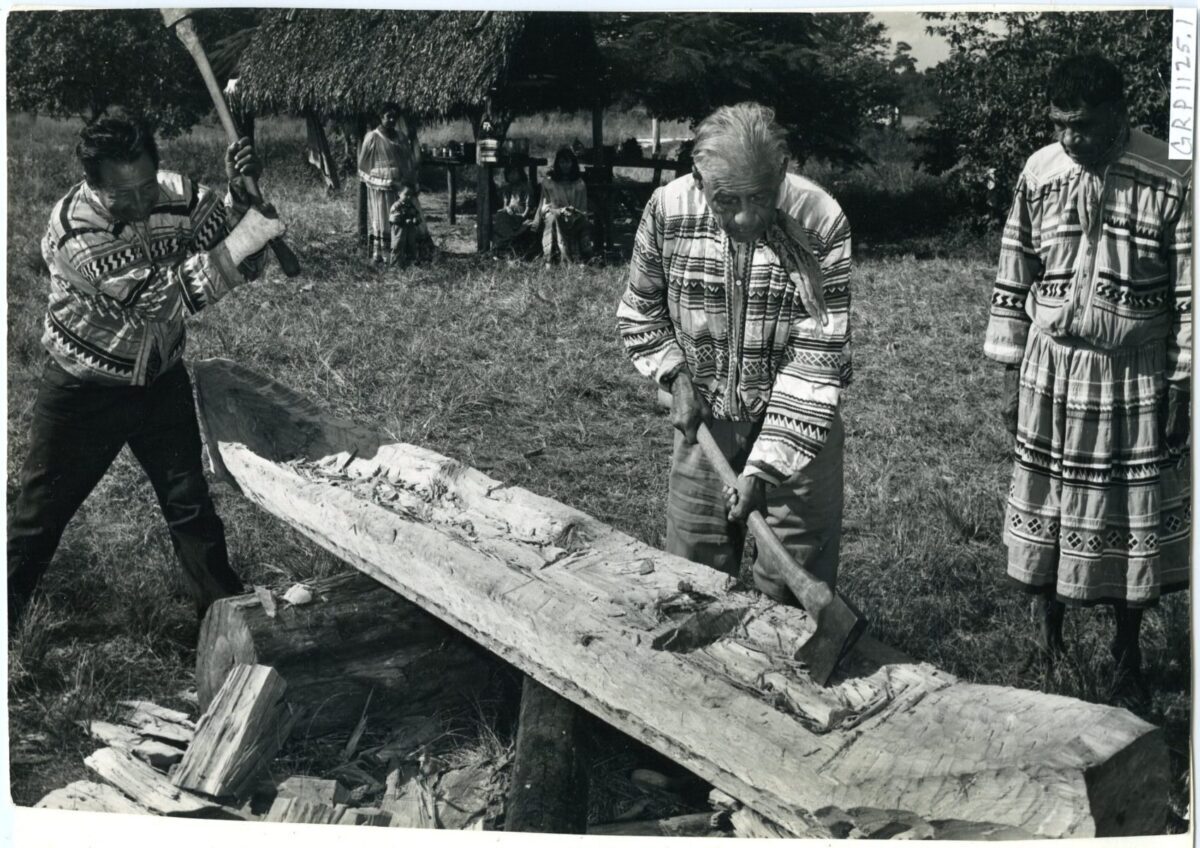

In our featured photo this week, three men in traditional Seminole clothing carve a canoe in front of a chickee in 1958. From left to right, the men are identified as Josie Jumper, Frank Tommie, and Sam Huff.

Seminoles on the Miami River, January 29,1912, Florida Memory Project

The Importance of Canoes

Prior to the development and drainage of the Everglades, dugout canoes were a vital form of transportation for Seminoles. Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the subsequent Seminole War period, Seminoles fled to the wild inland Everglades to evade US troops. Seminoles are the only tribe that has not signed a peace treaty with the US government. By the 1840s, the Seminoles remaining after removal were the only indigenous peoples left in their ancestral homelands in the Southeast. This was a period of intense isolation and distrust. Seminoles lived almost exclusively in the Everglades, protected by a land most non-Seminoles deemed ‘inhospitable’. Hunting, fishing, and farming were important for Seminole survival in the Everglades. With extensive knowledge of the waterways and hammocks, Seminoles would pole canoes on trails through the sawgrass.

Although they were important tools for survival for Seminoles, they also represent connection. Entire families could travel from camp to camp with their belongings. Men could hunt and fish from the canoes. The poles used to propel Seminole canoes even have a sharp needle on one end, so they could “gig” fish from the canoe. Canoes also allowed Seminoles to bring hides, plumes, and other items to trade at trading posts. These trading posts created tenuous early connections between Seminoles and non-Seminole settlers. Places like the Stranahan House in Fort Lauderdale and Ted Smallwood’s Store in Chokoloskee were vital resources for isolated Seminoles in this era. This way, they could still trade while keeping their lives, families, and camps separate.

The End of the Water Highway

Florida is a land of water. Even now, “The Sunshine State” is defined by its relationship to water; both on the coasts and inland. But, prior to the early 20th century, this relationship was even more intimate. Seminoles were dependent on the water, and adapted to the shifting water levels to survive. As we have discussed in previous blog posts, the Everglades as we know it is not how it has always been. The Everglades is a large wetland prairie supported by a unique sheet flow. Water from the Kissimmee River would flow into Lake Okeechobee. Typically, as the wet season progressed, water from the lake would spill south, and feed a vast, slow moving river. This “River of Grass”, a term coined by Marjory Stoneman Douglas in the 1940s, is essential to support the diverse plant and animal life that inhabit the Florida Everglades.

Three large changes would spell the end of Seminole isolation and change the Everglades forever. The first was the development of new railroad systems throughout Florida. This brought many new residents, who sought to tame the land. Subsequently, massive drainage projects after the turn of the century lowered water levels. As the development of these drainage and canal projects intensified, the Everglades ecosystem suffered. Finally, the cutting of the Tamiami Trail (US 41) across the Everglades was completed in 1928, linking the east and west coasts. The sheet flow was no longer unimpeded. Instead, development sought to control the flow of water. Unfortunately, this resulted in massive environmental impacts we are still dealing with today. Many of these factors made extensive travel by canoe, which was a typical form of transportation in the waterlogged Everglades, impossible.

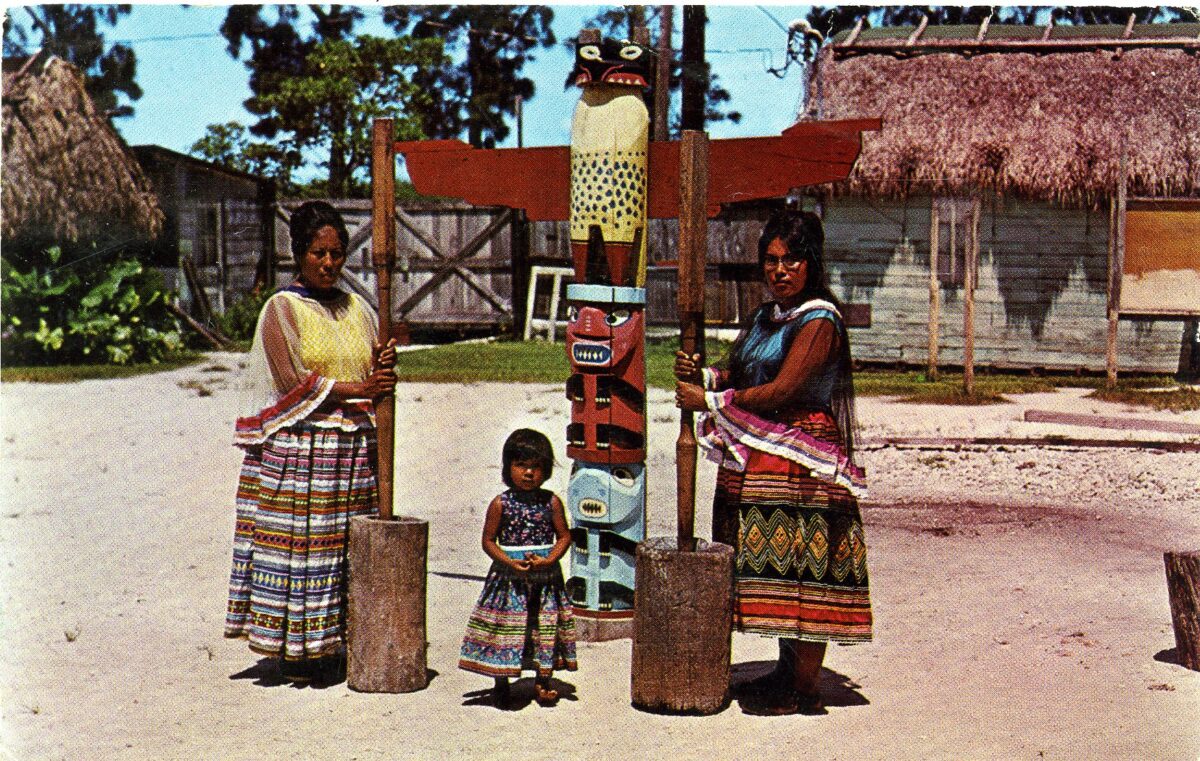

Postcard, 2003.15.242, ATTK Museum

Seminole Dugout Canoe Exhibitions and Models

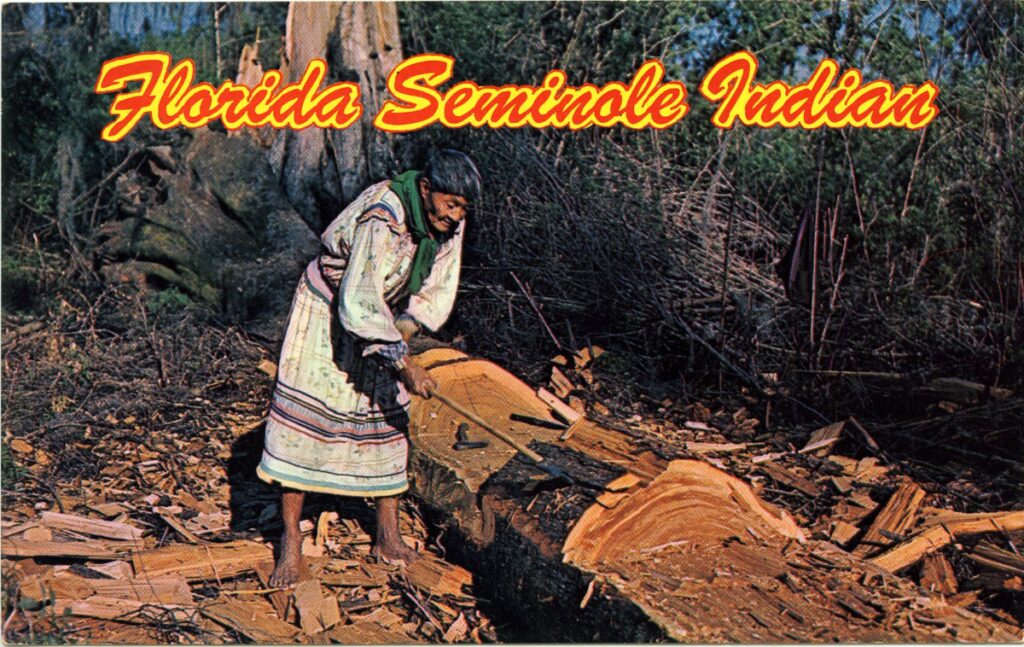

Canoes were still important to Seminole culture as tourism became an economic resource in the early 20th century. While not used as extensively as before, they still represented a deep connection to the water and the Everglades. At tourist camps, tourists could view exhibitions of canoe carving, woodworking, and other day-to-day crafting. Above, you can see a postcard sold as a tourist souvenir in the 1960s. In it, Charlie Cypress carves a canoe with an axe at Silver Springs. He was one of the most famous Seminole canoe carvers, and the most photographed. Cypress and his family often stayed at the Seminole Village at Ross Allen’s Reptile Institute at Silver Springs in the early to mid-20th century. Cypress lived to be over 100 years old and was a master canoe carver.

Smaller, model canoes also became a popular woodcarving item. Below is a model canoe made by Henry John Billie in the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collection. It is approximately six feet long, and half a foot wide. Model and toy canoes, like this one (although this one is modern), were sold as souvenirs at tourist camps and villages throughout the 20th century. Much like patchwork, dolls, and baskets, toy canoes like this became staple crafts purchased by visitors. Now, they represent an important piece of Seminole culture and history.

1993.23.1, ATTK Museum

What Makes a Seminole Dugout Canoe Unique?

Skilled artisans make Seminole dugout canoes out of bald cypress. Cypress heartwood has a special oil (cypressene) resistant to rot and water damage. Some canoes could be up to thirty feet in length. Unfortunately, not much old growth cypress remains in Florida due to logging in the first half of the 20th century, so modern canoes are much shorter. Seminole canoes have an upswept stern, and a pointed bow to cut through the sawgrass. Unlike other canoes propelled with a paddle, Seminole canoes use a long pole ideal for shallower water. The pole is dropped all the way through the water to the ground, and the boat is pushed through the water. The end of the pole typically has a small paddle to steer the boat.

Seminole canoes are made with a single piece of bald cypress and shaped with axes and adzes. The log is shaped into the rough preform, with the sides smoothed down and straightened. Master craftsmen make crosscuts into what becomes the belly of the canoe and knock them out with an axe in chunks. Then, they use adzes for finer detail work and tighter curves. Modern canoes are often made with power tools like chainsaws and power sanders, depending on the artist.

A Continued Tradition

In 2011, the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum documented a project of Seminole canoe carver Pedro Zepeda, aptly named The Canoe Project. In it, Zepeda and several other Tribal Members made a dugout canoe, which was documented by the Museum’s Oral Historian. Then, the group set out to Chokoloskee, to the Smallwood Store. Ted Smallwood’s Store was a vital trading post opened in 1906. Seminoles would trade plumes, hides, and other goods. The trading post era was especially important in building relationships between the isolated Seminoles and non-Seminole settlers. This first canoe journey soon encouraged Zepeda to expand his idea and include more people. Only a few years later, Zepeda and other Tribal Members participated in the first canoe journey. The nine-mile trip down the Turner River to Chokoloskee is documented in a Seminole Tribune article.

In a lecture hosted by the Amelia Island Museum of History in November 2020, Zepeda spoke about Seminole canoes, their history, and what makes them different from other canoes. Zepeda began carving at fourteen years old, and now wants to encourage canoe carving as a modern Seminole tradition. Master carvers like Zepeda hope to spur interest and reinvigorate canoe carving as a Seminole tradition. “Why are they important?” Zepeda states in his lecture, “Is it just an object, or is it more than just an object…For Seminoles at least…these objects contain so much cultural knowledge.” (17:00) That cultural knowledge is one Zepeda and other carvers work hard not to lose.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.