Laura Mae Osceola: Powerful Voice of the Seminole People

Welcome back to Women’s History Month! Today, we are continuing our journey spotlighting strong, resilient, and impactful Seminole women through history. In this installment of our series, we journey back to the 1950s when the Seminole Tribe of Florida achieved federal recognition.At just 21, Laura Mae Osceola emerged as the interpreter and spokesperson for the Seminoles, addressing Congress during a time when many Seminoles did not widely speak English.

Osceola was fluent and well-spoken in English, Mikasuki, and Creek. Her linguistic prowess paved the way for her historic role as the first Secretary of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, solidifying her as an influential advocate. We will delve into her life and impact, as she navigated the complexities of federal recognition, government dynamics, and adapted to a new world.

In our featured image, the first Tribal Council of the Seminole Tribe of Florida sits together. Seated from left to right: Howard Tiger, Laura Mae Osceola, Billy Osceola, Mike Osceola, John Josh, and John Cypress. Charlotte Osceola stands to the left and Betty Mae Jumper to the right. A note on the back of the associated print states: “Frank Billie missing from this picture” and “1958 First Council Members.” This meeting comprises members of the Constitutional Committee.

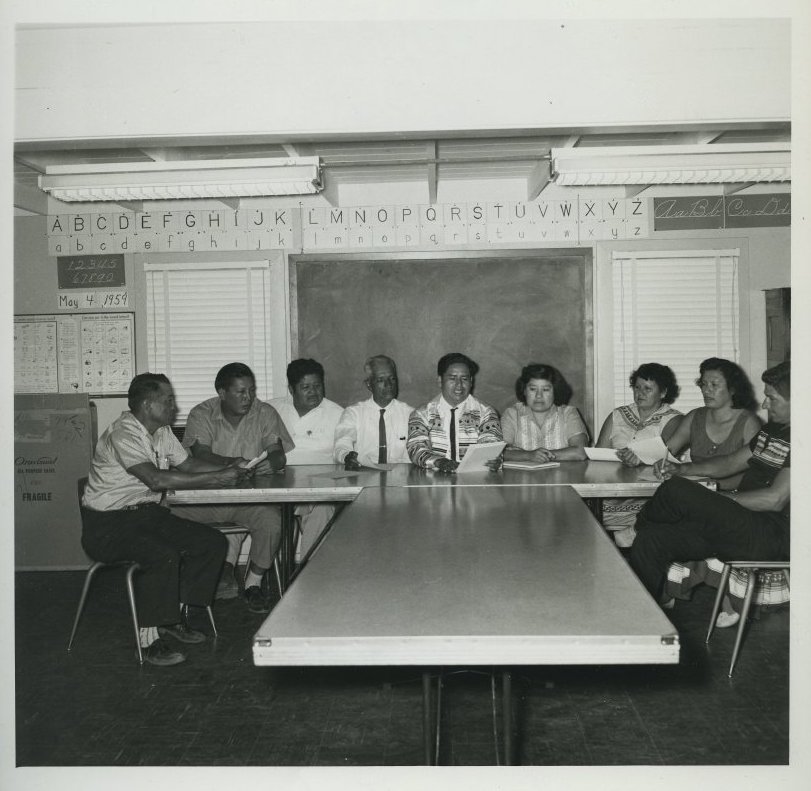

Below, you can see a black and white photograph of the Tribal Council gathered around a classroom table in 1959, two years after obtaining federal recognition. From left to right are: Frank Billie, Mike Osceola, John Cypress, John Josh, Billy Osceola (Chairman), Laura Mae Osceola (Secretary), Betty Mae Jumper, Charlotte Tommie Osceola, and Howard Tiger.

2009.34.780, ATTK Museum

Indian Termination

In 1953, Congress sought to abolish tribes within the United States. Additionally, Congress advocated for relocation from reservation land to urban areas. The United States government would then sell, dissolve, or distribute the relinquished lands. House Concurrent Resolution 108 of 1953 states that: “at the earliest possible time, all of the Indian tribes and the individual members thereof located within the States of California, Florida, New York and Texas, should be freed from Federal supervision and control and all disabilities and limitations specifically applicable to Indians.” Between 1953 and 1970, Congress would initiate over 60 separate termination proceedings against American Indian tribes, and over 3 million acres of land were relinquished.

Termination “ended federal recognition of affected tribes and the federal aid and services that came with that recognition. It also ended federal trust status for affected reservations and the protections granted by such status. In many cases, termination meant the transfer of federal jurisdiction over criminal and civil matters on reservations to state authorities.” Termination policies such as these were devastating for tribes, who had little experience operating in the white man’s world.

Language barriers, lack of formal education, and few transferrable skills to this new world’s expectations made the transition almost impossible, despite the government’s propaganda saying otherwise. Individuals were entirely off from their communities, and their source of support and cultural kindship. The intention behind these policies was, for once and for all, to solve the “Indian Problem.” The “vision was that eventually there would be no more BIA, no more tribal governments, no more reservations, and no more Native Americans.” The effects of these policies and how they reshaped Indian Country is devastating. Many lost their cultural identities, homes, ways of life, and communities.

A Long Train Ride

With the turmoil of Indian Termination lurking, many leaders within the Seminole communities could see the danger. They feared they would lose their lands, their identity, and their community. How would they get healthcare? Housing? Many lacked formal education, and most Seminole elders did not speak English. “They were just going to let us go with no help at all. They were just going to let us go into the white man’s world,” Laura Mae Osceola stated (21 Mar 1993, South Florida Sun Sentinel).

So, the elders decided to plead their case with Congress and ask for more time. Seminole elders chose Laura Mae Osceola, just 21 years old, as interpreter. Osceola was fluent in Mikasuki, Creek, and English. She had gone to grade school in North Carolina, high school in Oklahoma, and college preparatory school in Mississippi. This made her an accomplished candidate, as “we could count on our hands how many high school graduates we had at the time” recalls Osceola (21 Mar 1993, South Florida Sun Sentinel).

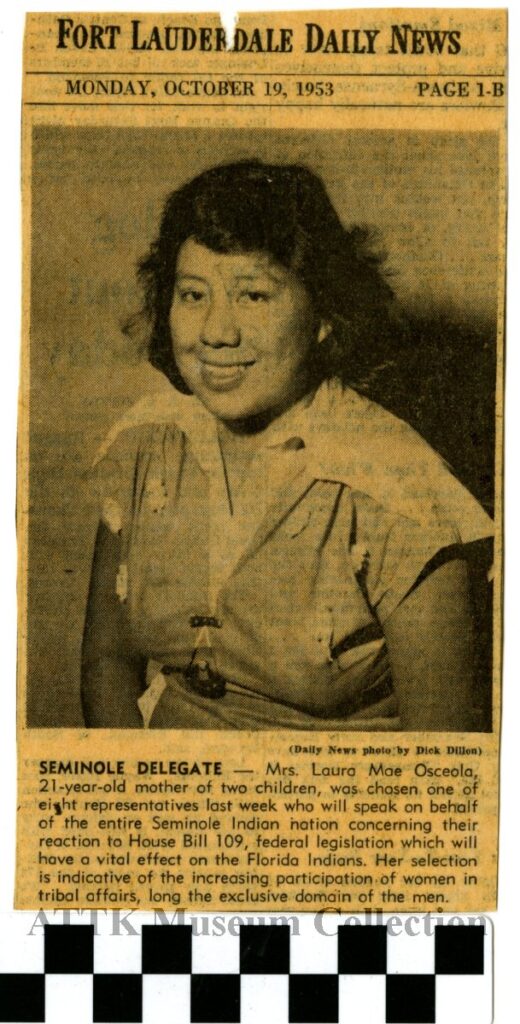

2005.1.203, ATTK Museum

So, in March 1954, Osceola and 11 other Florida Seminoles boarded a train bound for Washington D.C. Other delegates included Sam Tommie, Billy Osceola, Taby Johns, Josie Billie, Jimmy Cypress, Mike Osceola, Curtis Osceola, and Henry Cypress (2005.1.1488, ATTK). They sought to gain time – time to bridge the gap and have a fighting chance. Laura Mae Osceola stated: “I told everybody before, ‘Just stick to the point: Don’t tell them we don’t want to run our business. But we want to run it when we’re ready, when we have educated Seminole leaders’” (21 Mar 1993, South Florida Sun Sentinel).

“I was the only woman,” Osceola recalled. “But I had a big mouth, and I wanted to help my tribe” (09 Feb 1987, Tallahassee Democrat).

An Interpreter for Her People

So, she did. During their time testifying before Congress, Osceola sat beside each elder, translating their words. Additionally, she testified herself, saying:

“And for my people I am pleading with you to give them more time….Maybe the children we have in school now will be able to come here as representatives or senators just like you white people do; maybe be a doctor or a lawyer, or whatever they want to be. But we, the women of the Seminoles, are trying our best to teach our children so that they can take that responsibility” (21 Mar 1993, South Florida Sun Sentinel).

Seminoles continued to lobby against termination policies that would withdraw federal services from their tribe. The US government never aimed another termination policy aimed at Seminoles. But the threat spurred change.

Federal Recognition

In 1957, the Seminoles would organize a Tribal Council, and receive federal recognition, becoming The Seminole Tribe of Florida. Under the Council Oak tree, Seminoles would develop a formal constitution and corporate charter, establishing a two-tiered government. The BIA sent Sioux Indian Reginald “Rex” Quinn to assist them in drafting the constitution and bylaws. Twenty years later, Quinn would recall the meeting under the Council Oak in the University of Florida Oral History Program.

Quinn would remember: “It was a natural meeting. There were no chairs or anything. There was a small table and a couple of chairs for me and the superintendent to sit on. The rest of them were either standing or sitting on the ground. Bill and Laura Mae and Billy got up, and they explained to the group what had transpired and that they were now in a position to go ahead with the process of setting up a Tribal government…. After much discussion the general council selected a constitutional committee. Bill Osceola was made Chairman of that committee, Mike Osceola was made secretary of that committee [and] Laura Mae was designated as interpreter. Billy Osceola and John Henry Gopher from Brighton were on that committee. Frank Billie from Big Cypress and Jackie Willy from Dania made up [the rest of] that committee.”

A Continuing Voice

Laura Mae Osceola was the appointed Secretary-Treasurer. She held the position for a decade. Despite the huge win of federal recognition, the next decades were tough. Many of the same issues remained. But Seminoles were determined to have their own voice. In the meantime, Laura Mae Osceola was preoccupied with one way she knew she could affect change: motherhood. “I was obligated to raise my kids to get the education that they needed. The other ladies raised theirs, too. This was our goal” (21 Mar 1993, South Florida Sun Sentinel). In that role, Laura Mae advocated for Seminole rights. She worked hard to help educate and further the interests of her people and her tribe.

Often, Laura Mae would babysit children at her own home while their parents would attend night classes (2009.34.596-.599, ATTK Museum). Below, you can see Laura Mae (center) assisting William D. Boehmer (left) and Leoda Jumper Osceola (right) during an adult education course in 1956.

2009.34.677, ATTK Museum

Her Legacy

At her funeral in 2003, adopted son and former Chairman James E. Billie would say that: “She helped us cross hurdles, which then were education and economics. Leadership is what she put in us.” Her son, the late Max Osceola Jr., would remember: “Sometimes I wouldn’t see my mother for a week, but she would tell me, ‘I’m working for the tribe’” (10 Oct 2003, South Florida Sun Sentinel). Max Osceola Jr., served as the Hollywood Councilman from 1985 to 2010 as well as being the former Education Director.

In 2007, he wrote a statement to the Seminole Tribune during his reelection bid for Tribal Council, stating: “The future is bright and the strength of the Seminoles is not measured in money but by our character of ourselves which is taught to us by our Elders who saved this tribe from termination 50 years ago.”

In a recent news article from Fox 4 News, Tina Marie Osceola, current Tribal Historic Preservation Officer and Acting Executive Director of Operations of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, talked about the role of motherhood for Seminole women, and how this legacy has changed the course of Seminole life.

She states: “We mother our community, we mother our tribe, we Mother Earth,” she said. “Women in the Seminole Tribe of Florida, we have a really strong history of being part of that very fabric of the creation of the Seminole Tribe of Florida as a government.” Laura Mae Osceola was one of these women, and “She represented that when you’re in tribal office, it’s not just about your family, not just about your clan, it’s not about all of that,” Tina explained. “It’s about everyone in the tribe.”

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Lakeland, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.