Teaching from the Heart: Love and Language with Lorene Bowers Gopher

Happy Friday! Throughout March, Florida Seminole Tourism is spotlighting significant Seminole women every week on our blog. In the latest installment of our Women’s History Month series, make sure to grab your backpack and sharpen your pencils! This week, join us to learn more about the incredible Seminole teacher Lorene Bowers Gopher.

During her long career, Gopher dedicated her time to education, the preservation of Seminole Culture, and the preservation of the Florida Creek language. In addition, Gopher would become Brighton’s Cultural Program Director. She would develop community programs aimed at preserving Seminole culture, art, foodways, and the Creek language. Today, we will explore Gopher’s lasting legacy and witness the enduring impact her passionate teaching had on the education of Seminole children.

In our featured image, you can see a group of children lined up at the Brighton Indian Day School, circa 1951-1952. They are (L to R): Josephine Huff, Elaine Johnson, Mildred Bowers (rear), Lawanna Osceola, Lorene Bowers, Elsie Jean Bowers (rear), Gladys Bowers, Richard Smith, Texas Tiger, Billy Micco, Coleman Josh, Russell Osceola, Jerry Micco, Jim Shore, William D. Boehmer, Brown Shore, Eddie Shore, Jimmy Scott Osceola (2009.34.1644).

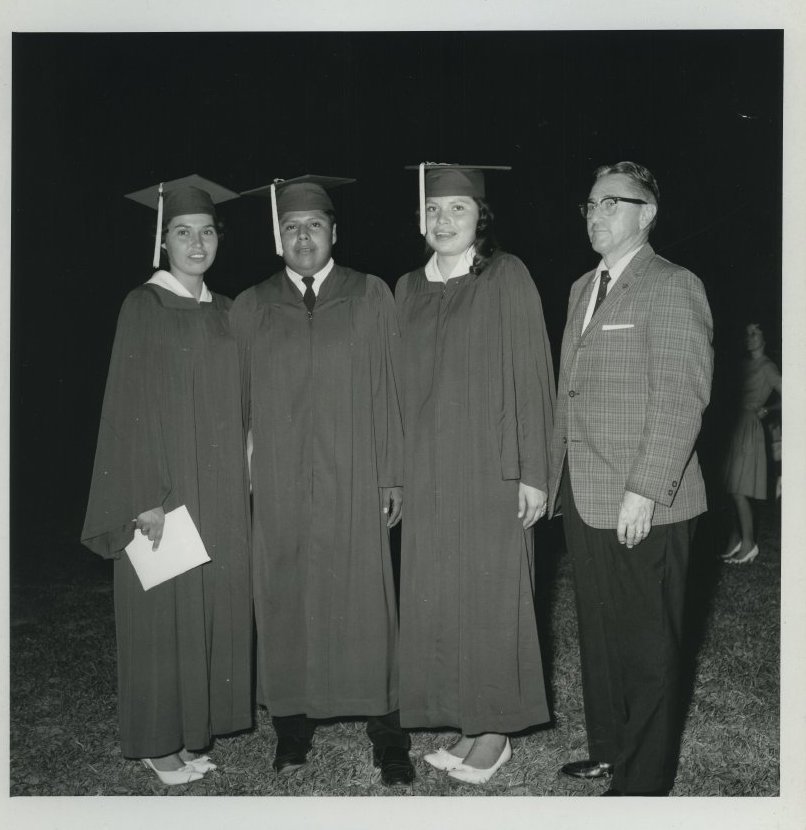

Below, you can see Lorene Bowers (center) with Connie Johns and Jim Shore in 1962. They sit on the front steps of Okeechobee High School in Okeechobee, FL. The trio are the Seminole graduating class from that year.

2009.34.1904, ATTK Museum

Early Life

Gopher dedicated her life to education and cultural enrichment from a young age. Born in 1945, she grew up in a traditional Seminole family camp near Lake Okeechobee. Like many of her generation, she learned English as a second language. She attended the Brighton Indian Day School. You can see Lorene with her class in our featured image, along with William Boehmer. In a 2015 Seminole Tribune article about Gopher being honored by the Billy Osceola Memorial Library, her son Lewis Gopher stressed that “[Lorene] did everything possible to attend school and get an education – even if that meant completing her homework by the light of a lantern. ‘She had a drive inside of her,’” he shared.

Looking back, it is apparent that Gopher had a strong will to achieve and learn from a young age. Newspaper articles from the 1950s and 60s often mention her name in relation to the Brighton Indian Day School. In reading them, her desire and thirst for knowledge are very present. On April 18, 1958, she qualified for the Okeechobee County district final Spelling Bee (2005.1.1372, ATTK Museum). In another article, her name is among those from the Brighton Reservation who were enrolled in Federal Indian Boarding Schools in Oklahoma and Kansas, travelling by bus from the Brighton Reservation (2005.1.165, ATTK Museum). In one more, she earned 2nd place in her category for the Girls 18 & under high jump at a Field Day competition (2005.1.2047, ATTK Museum). Gopher would be one of the first Seminoles to earn her high school diploma. Below, you can see another shot of Gopher (center right). She stands with other Seminole graduates, Connie Johns and Jim Shore, in 1962.

2009.34.1789, ATTK Museum

Dedicated to Education, Culture, and Language

In particular, preserving the Florida Creek language was an area where Gopher saw a deep need. The elders who knew Creek were dying. Meanwhile, they had encouraged their children to speak English. This, paired with the closing of the reservation school in the 1950s, as well as moving away from the traditional family camps, meant Creek was being spoken less and less.

In a 2012 Seminole Tribune teacher profile on Gopher, she explained how she realized the need for Creek classes. “If I don’t know something (in Creek), I don’t have my mom or grandma to ask, so I ask my older sisters and they’ll help me out, but there are no resources where I can go to find out, so I’m just racking my brain,” she said. “I realized that we were leaving our language to our younger people,” she said. “My kids could understand it but couldn’t speak it. We’re probably the last generation of fluent speakers.” The idea of losing the Florida Creek language in only a few generations drove her to dedicate her career to preserving it.

In 1979, Gopher and Jennie Shore met with a Muscogee Creek from Oklahoma, Dean Tiger. Gopher and others painstakingly adapted a similar alphabet to his, for Seminoles to be able to have a system of writing in place. Prior to this, Seminoles passed language down orally, and even fluent speakers had no way of writing it. She then helped establish a written form of Creek and worked as a Creek language consultant. Throughout the next few decades, Gopher worked for the Seminole Tribe in a number of capacities, even being intimately involved in the establishment of the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum. But, language was always in the back of her mind.

Language Programs Develop

Slowly, Gopher would help establish more and more immersive programs for Seminole youth to learn Creek. At first, it was after school programs for Seminole children attending school in Okeechobee County. Then, she realized they needed more of their time. Gopher “arranged with the School Board of Okeechobee County for her to teach at Seminole Elementary School twice a week in place of study hall or another elective.” She taught there for five years.

Next, Gopher developed a “Pull Out” Program, where kids were taken out of their schools every Friday to the reservation for a full day of immersion. But, even this was not enough time. They needed a captive audience, to get the kids engaged and interested. Soon, Pemayetv Emahakv opened as the first Tribal charter school in the Eastern United States. The curriculum made Creek language a daily part of Seminole children’s education and immersed them in the language and culture.

Opened in 2007, Pemayetv Emahakv focuses on teaching the language orally first before learning how to write it. “You have to know how to say the word before you can write it” quipped Gopher in a Palm Beach Post article about the language program (09 Dec 2007, Palm Beach Post). Despite roadblocks, she knew that preserving this part of the language was one that needed to happen, even if they failed.

So, they taught. In the same article, Lorene emphasized this. It reads “’See this?’ Lorene Gopher asks one afternoon, pinching the fabric of her skirt. ‘Anyone can make these clothes or learn to cook the food. But only we will speak the language. Without our language we have nothing” (09 Dec 2007, Palm Beach Post).

Pemayetv Emahakv Today

Today, Pemayetv Emahakv continues to offer immersive Creek language and culture classes for students on the Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation. In 2015, Pemayetv Emahakv launched an immersive Creek Language program, with direction from Jennie Shore. Just recently, the Brighton community broke ground on new facilities to house this unique immersion program as well as a separate complex for the Boys & Girls Club, library, and a community cultural center.

At the groundbreaking, the community honored the three women who had the most impact on the program: Jennie Shore, the late Lorene Bowers Gopher, and the late Louise Jones Gopher. It took time, but their dream was realized. In a Seminole Tribune article covering the event, Jennie Shore is quoted saying: “Most know that there is a large gap in those who speak the native tongue and those that do not, it is something that wouldn’t be learned unless the person is immersed in it. Now for the first time in a very long time, the children are learning and playing all while speaking the language. It makes me happy.”

Lorene’s brother, Brighton Councilman Andrew Bowers Jr. also spoke at the event. He stated: “I’ve been thinking about what I want to say and what came to my mind is three Seminole ladies. I would focus on what they did, not what I might have done. They saw that the Seminole way of thinking, Seminole way of living, Seminole way of talking, was being lost. So they started out thinking: how can we teach this and continue this?”

Florida Folk Heritage Award and Legacy

The State Department of Florida posthumously awarded Lorene the Florida Folk Heritage Award in 2015. She received the award based on her “her strength of character and commitment to the cultural integrity of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.” Additionally, The Florida Creek Language, and Florida Creek Dictionary, was a particular passion project for Gopher. She completed the dictionary shortly before her passing in 2014, dedicating the last few years of her life to its completion.

In 2015, her son Lewis Gopher explained more about what drove his mother. He shared, “She always wanted the traditional way to be carried on, she wanted to spread her knowledge…..She never wanted to earn an award,” Lewis stated. “Her goal was to teach the kids, to be a good person, and that makes me want to do more and to be a better person.”

Lorene was the fifth Seminole to receive this award, joining Susie Jim Billie (1985), Betty Mae Jumper (1994), Henry John Billie (1998) and Bobby Henry (2001). Below, you can see Lorene Gopher’s family receiving the award in her honor.

Via the Seminole Tribune

Gopher’s legacy lies in how she “helped rejuvenate and safeguard the Florida Creek language, taught hundreds of children about the old ways and completed her life’s work by handing down a rich, preserved treasure trove of tradition and culture to the next generation of Seminole Indians.” Even now, her work continues to teach Seminole children the Seminole culture and Creek language. Through her efforts with Pemayetv Emahakv, the Florida Creek Dictionary, and all current teachers and community leaders she taught and touched, Gopher’s legacy continues to inspire.

Check back in next week for another installment of our Women’s History Month Series! Next Friday, join us to learn about the Voice of the Seminole Tribe, Laura Mae Osceola.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Lakeland, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.