Exploring Cowkeeper’s Powerful Legacy with the STOF-THPO

Ready to pick up a good book? Explore the recently released publication from the Tribal Historic Preservation Office, delving into the world of Seminole cowkeepers, cattle, and the enduring legacy of Ahaya. Titled “Cowkeeper’s Legacy: A Seminole Story,” the book is now accessible online. Join us this week to delve into its content and discover the rich history of the influential Seminole cowkeepers who have played a pivotal role in shaping Seminole cattle for generations. By the end, consider one question: What is Cowkeeper’s Legacy for the Seminole Tribe of Florida?

In our featured image this week, you can see a group of Seminole men standing on fence posts holding branding irons during round-up on the Big Cypress Reservation in 1949. Josie Billie (marker JB) is fifth from the left, and Morgan Smith (marker MS) is third from the left. Both were instrumental in the Big Cypress cattle operation.

What are Seminole Cowkeepers?

Seminoles have been involved in Florida’s cattle and cowkeeping industry since its inception. Ponce de Leon brought the first Andalusian cattle to Florida in 1521. The Spanish had intended to colonize Florida, and the cattle herds were an integral part of supporting their colonies like St. Augustine.

They had “hoped to take land from the Calusa, ancestors of the modern Seminole Tribe of Florida. However, the Calusa were prepared for the invaders and drove the first colonization attempt back to the sea” (STOF-THPO 4). By the 1700s, the Spanish had left their failed colonies, leaving the cattle behind. These prime Andalusian cattle became wild cows that adapted and thrived in the wilds of Florida. Thus, they became prized for their hardiness and resistance to parasites.

Soon, these cattle became an important part of Indigenous foodways and culture. Native communities became intimately tied to their herds, and the first Florida cowboys were undoubtably Native. Although the history of Seminole cattle has ebbed and flowed over the tumultuous centuries, cattle are still an incredibly important part of Seminole culture today.

The story of these first Seminole ancestor herds, to the Seminole cattle operations of today: “comes from the spoken histories of the Tribe, from the written words of history, and from the artifacts of the past unearthed by Tribal archaeologists. It is a story of growth and hardship, of peaceful trade and open war, and most of all of endurance” (STOF-THPO 4). In this new book, this story is explored and expanded on, outlining the legacy of not only the first Cowkeeper, but each Seminole cowkeeper, man and woman, who followed.

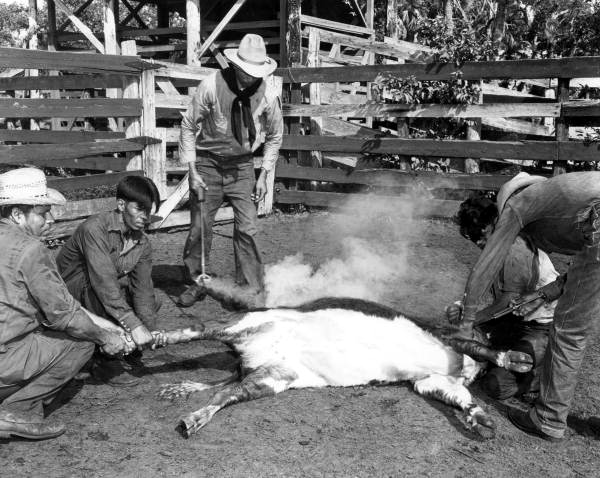

Above, you can see Andrew Bowers, Joe Henry Tiger, and Willie Gopher Sr. branding cattle on the Brighton Reservation, 1950.

Ahaya: The Cowkeeper

Although not the first Seminole ancestor to practice cowkeeping, Ahaya was one of the most successful historical cattle leaders in Florida history. An Oconee leader, Ahaya took control of Alachua near Gainesville in the early 1700s. We know the area as Payne’s Prairie, named thus after the son of Cowkeeper. Soon, Ahaya slowly gathered abandoned and feral Spanish cattle to grow his herd, and ultimately built a thriving cattle industry. He would go on to amass an extremely large herd of cattle, and found Cuscowilla (now, Micanopy).

By 1775, these Seminoles were working 7,000-10,000 head of cattle. Notably, they would use trained cattle dogs, a practice that would be picked up by Florida Cracker Cowboys. We have talked about Florida Crackers in a previous blog post, and how many of their successful tactics were borrowed or taught to them by Seminole cowkeepers.

Unfortunately, conflict would interrupt this golden era of Seminole cattle. Rising tensions and aggression between Seminoles and American settlers often revolved around cattle and grazing lands. Furthermore, these conflicts would significantly contribute to the Seminole War period, which would decimate the Seminole people.

The US Army worked to remove all Seminoles from Florida, and “As part of the war strategy, U.S. Army General Jesup ordered the burning of Seminole crops and the seizure of Seminole cattle and horses” (STOF-THPO 11). The Seminoles who continued to work cattle during this time did so at great personal risk. Survival of the Seminole people and their culture was the ultimate goal, and many deemed cattle ranching too dangerous. Seminoles survived this dark and desperate period, despite being reduced to only a few hundred survivors.

A Revival Realized…

The renaissance of Seminole cattle would happen in the 1930s in an effort to economically support the financially struggling Tribe. Five Seminole men spearheaded the efforts on the Brighton Reservation: Frank Shore, Charlie Micco, Naha Tiger, Willie Gopher, and Willie Tiger. All five of these men had ranching experience, as well as a wealth of traditional knowledge to support their efforts. They worked with US Agricultural Agent Fred Montsdeoca to learn modern ranching techniques and give this venture the best possible chance of success.

The United States Government purchased 547 cows, sourced from Dust Bowl devastated ranches out west, to begin the fledgling enterprise. But, the venture was plagued with difficulties, and “the harsh conditions of transport combined with the new and vastly different environment and poor grazing conditions of the Brighton Reservation caused incredible health problems for the herd. Only an estimated 200 head of cattle survived at the end of the first year” (STOF-THPO 15).

Despite the struggles, these Seminole cowkeepers put out monumental effort to make Seminole cattle succeed, as they “built mineral boxes to add nutrients to the grazing pastures, windmills all across the reservation to pump clean water, planted higher quality grass, and installed fencing and sink wells” (STOF-THPO 15). By 1939, there were over a thousand head of cattle on the Brighton Reservation. Soon, Seminoles would take over the operation from the US Government.

The Seminoles formed the Brighton Indian Cattle Enterprise, with Charlie Micco, John Josh, and Willie Gopher as the first trustees. Soon, the Big Cypress Cattle Enterprise was formed on the Big Cypress Reservation, led by Morgan Smith. Smith, known for his large size and even larger influence, was instrumental in setting up the Big Cypress cattle operation. Below, you can see a shot from a contemporary Smith Family cattle drive.

Today’s Seminole Cowkeepers

Today, the Seminole cattle industry is comprised of some of the most knowledgeable and sophisticated cattle operations in the country. The Seminole Tribe is one of Florida’s top beef producers. For the Seminole Tribe of Florida, the cattle industry is going strong. In 2018, a dozen of the 29 female Seminole cattle owners reestablished the Florida Seminole CattleWomen, Inc. It had originally been established in 2009 as a chapter of Florida CattleWomen, Inc. as the Seminole CattleWomen’s Association.

Many members are descendants of the original cattleowners of the 1940s and 50s, continuing their family legacy. Seminole women have long been involved in the cattle industry alongside men, often owning their own herds. The Seminole Cattlewomen of today follow in the footsteps of historic cattlewomen Ada Tiger, then the next generation of Ada Pearce, Lena Gopher, Arlene Johns, and Betty Mae Jumper. Below, you can see Seminole women around a fire on a cattle round up, Brighton Reservation, 1955. Irvin Peithmann, who was the focus of a previous blog post took the image.

Outside of the Tribe, Seminoles also hold positions in Florida’s cattle industry overall. Florida CattleWomen Inc. installed Lucy Bowers as parliamentarian on the executive board in 2022. Just a few years prior, Alex Johns became the first Seminole President of the Florida Cattlemen’s Association.

When Johns finished his term in 2019, he stated: “Who would have ever thought that a poor little Indian boy would grow up and rise in the ranks to lead a prestigious organization like the FCA…We must continue to share our story and our passion so much that it becomes synonymous with the public that cattlemen and women are great stewards of the land and animals they oversee. The world needs us, though many of them will never realize it. It’s our job to keep up the fight to make sure we are still around for another 500 years.”

Then, he turned the reins over to incoming President and friend Matt Pearce, who responded: “In my mind, you are the ultimate cow keeper.”

We encourage you to read and explore this new book from the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office to learn more. While reading, note the many influential Seminole men and women who have impacted and shaped Seminole cattle over the centuries. Read about Ada Tiger, mother of Betty Mae Tiger Jumper, and her life as an independent Seminole cattlewoman in the 1920s. Explore Red Barn, and the long-lasting impact these early cattle ventures would have on the Seminole community for generations.

Many of these Seminole cowkeepers, like Charlie Micco, Frank Shore, Morgan Smith, and others, would not only build the cattle industry, but also build the Seminole Tribe of Florida through their efforts and their families. This Seminole story, like so many others, is rooted in resilience and a determination to survive against the odds. The full pdf is available here.

Source

The Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal Historic Preservation Office. (2023). “Cowkeeper’s Legacy: A Seminole Story”

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Lakeland, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.