A Journey Through Payne’s Prairie

Welcome back to our Seminole Spaces series! In this series, we explore places and spaces important to Seminole culture, history, and tourism. Last week, we talked about Seminole Cowkeepers, and learned a bit about the legendary Seminole Cowkeeper Ahaya. Ahaya amassed nearly ten thousand head of cattle, and drove them on the Alachua savanna near Gainesville by 1775. But, how did this Alachuan savanna become known as Payne’s Prairie? This week, we will explore Payne’s Prairie. There, the Seminole relationship with the land, as well as the landscape itself, has shifted and changed over time.

In our featured image this week, you can see a shot taken from the observation tower at the Payne’s Prairie Preserve State Park in 2022. Around 300,000 people visit the preserve annually to take in the wide grassy vistas and marshy woodlands. Home to hundreds of species of birds, fish, alligators, and even bison, Payne’s Prairie offers a glimpse of wild Florida steeped in Native history.

King Payne

Although Ahaya was famously known as “Cowkeeper,” this Alachuan savanna would not be named after him. Instead, history would name it after his son! Cowkeeper’s son, Payne (Snake Clan), would be a prominent leader and spokesman in the 18th and 19th centuries. Ahaya would die in 1783. Soon after, Payne would take on many of his responsibilities within the community that he built. Then, he would establish Payne’s Town, on the southern end of the prairie, around the 1790s.

Payne would expand on his father’s cattle empire, and broker trades with the Spanish at St. Augustine as well as Florida tribal communities as far away as Tallahassee. Politically, he “opposed joining the growing Creek Confederations…and proposed creating a federation of Florida tribes.” English and Spanish records refer to him as “King Payne,” and he was an incredibly well respected leader.

But, by 1812, Payne was in his 80s. American military interests threatened the prosperity that he had built at Payne’s Town. Although he wished to remain neutral, the council outvoted Payne and he soon found himself and his people embroiled in conflict. The militia, “operating out of Georgia…sought to exploit the shrinking Spanish presence and claim Florida for the United States.” These Seminoles, including Payne, allied with the flagging Spanish.

In September 1812, Payne’s soldiers “trapped and routed a large contingent of Georgian militia men, a blow that helped end what became known as the Patriot War.” But, Payne would not survive the fallout. He had taken a bullet early in battle and succumbed to his wounds days later, after trying to convince the remaining Seminoles to go to war against the United States (Blakney-Bailey 83). American soldiers would burn Payne’s Town to the ground in 1813. Although they didn’t know it, these conflicts would pave the way for the Seminole War period. The next hundred years would nearly decimate the Seminoles of Florida.

Payne’s Town

Previously living in Cuscowilla, Payne moved the town and established Payne’s Town sometime around 1790. For the next few decades, Payne’s Town would support a robust community of cattle ranching, trade, and agriculture. Thus, “To the Paynes [sic] Town Seminoles, business was usually separate from politics, and livestock was sold to Spanish, English, and American colonists, or any other person who would wanted to do business. In addition to ranching, the Seminoles produced agricultural crops for export. Rice was a particularly common commercial crop, as were smaller amounts of non-native orchard crops and plants. These crops, along with honey, beeswax, and bear oil, were frequently harvested, shipped, and traded” (Blakney-Bailey 76). This resulted in a thriving community, where Payne was known as a wealthy and confident leader. Notably, Payne’s Town was also considered a melting pot of many cultures, and Payne welcomed Africans who had escaped enslavement. These escaped slaves “sometimes established separate settlements, but other times were adopted as full members of the Seminole society” (Blakney-Bailey 86).

All of this allowed Payne’s Town to represent a robust number of cultures, as well as the Seminole experience prior to full out war during the Seminole war period. In the early 2000s, University of Florida researchers partially excavated Payne’s Town.

During these investigations, a variety of different artifacts were recovered, including: “Different parts of ceramic vessels, dozens of multicolored glass beads, glass bottle fragments, lead musket shot, a belt buckle and pieces of silver jewelry are a few examples of the materials found that likely were obtained from Anglo traders.” Additionally, “More traditional materials turned up, including animal bones, seeds, Seminole pottery and stone tools.”

This melding of cultures through trade provides an interesting facet of Seminole life prior to the Seminole War period and underscores the wide-range trade networks that supported robust and thriving native communities during this time.

Alachua Lake

Like we have discussed on the blog numerous times, water has one of the biggest impacts on Florida’s environment. During the late 1800s, an incredibly unique geological phenomena allowed a complete reorganization of this area. Where there is now and was savanna, a lake formed! In fact, Payne’s Prairie has been a lake a few times in history. But, the 1871-1891 period was the most dramatic on record. Below, you can see an image of the Alachua sink, taken during a geological survey.

State Archives of Florida

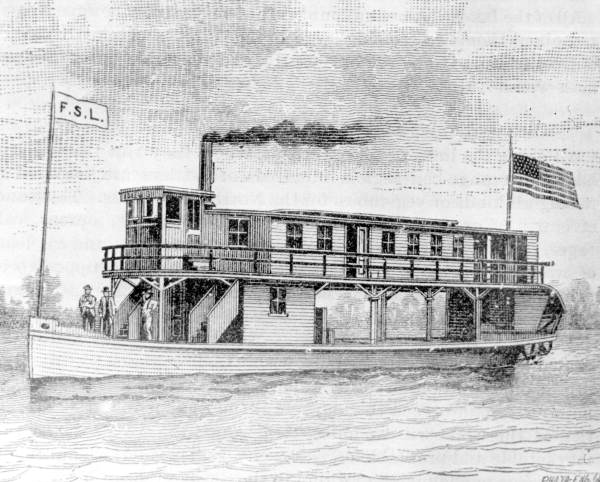

Decomposing vegetation blocked the sink for a period of about 20 years. This allowed water to pool in the basin, raise the water table, and Alachua Lake to form. During this time, locals established a booming steamboat industry, with steamboats bringing citrus and other goods to and from Gainesville and the burgeoning communities near Micanopy. These paddle-wheel steamboats provided the most direct travel. Below, you can see a drawing of the two-deck paddle-wheeler the F.S. Lewis, which served the Gainesville area circa the early 1880s. During a time in which travel within the state was incredibly difficult, steamboats provided a transportation solution.

But Alachua Lake would not last long. On August 21, 1891, the Polk County News reported that “for the past two summers, however, the waters have been gradually lowering, and about three weeks ago the decrease became more rapid, until nothing is now left of Alachua Lake except a few stagnant pools and turbid waters of the sink. It is estimated that over 40,000 acres of the fines grazing and agricultural land in the State of Florida has been reclaimed.”

State Archives of Florida

It is not unbelievable to think that Payne’s Prairie may hold Alachua Lake again someday. The water in the basin is dependent on the sink and the water table. Only a few years ago in 2018, “the Alachua Sink, which sends water from Payne’s Prairie to the Florida aquifer, took in less water than normal because rain raised the underground water table. UD-441, which parallels I-75, was underwater for a while” (03 Oct 2021, The Stuart News). Although it probably won’t see a booming steamboat industry again, Payne’s Prairie is a prime example of the ever-changing Florida landscape, and how water makes and shapes this great state.

Visiting Payne’s Prairie Preserve State Park

Today, Payne’s Prairie Preserve State Park boasts 22,000 acres of protected wet and dry savannah. It is a United States National Natural Landmark. It became Florida’s first state preserve in 1971. Historically, geologically, and biologically unique, the Preserve supports twenty distinct biological communities. It provides a variety of habitats that are the home to nearly 300 species of birds, alligators, fish, livestock, and many more native species.

The Preserve also supports wild-roaming bison and horses. This includes small herds of Florida Cracker horses (also known as marshtackie or Seminole ponies) and Florida Cracker cattle, which we have discussed in a previous post.

Both the horses and cattle are descendants of the Spanish-brought animals that came to Florida in 1521. Bison had once roamed the prairie. The Preserve reintroduced them in 1975. A small herd of 10 bison were placed on the prairie, and now the number is in the 40s (03 October 2021, The Stuart News). Below, you can see a group of bison gathered around a windmill on Payne’s Prairie, September 1976.

State Archives of Florida

The Preserve offers visitors a variety of outdoor experiences, including different trails open for biking, hiking, and horseback riding. The Gainesville-Hawthorne State Trail stretches 16 miles from Gainesville’s Boulware Springs City Park through Payne’s Prairie Preserve State Park and other conservation land. While exploring these trails, visitors will see a variety of wildlife, including bobcats, white-tailed deer, wild turkeys, raccoons, gray fox, alligators, snakes, woodpeckers, and more. Camping is available along Lake Wauburg in an established RV/tent campsite, with a primitive campsites available along the Chacala trail. With tens of thousands of acres to explore, Payne’s Prairie Preserve State Park has something for every kind of Florida adventurer!

As always, we encourage you to respectfully and thoughtfully explore these important Seminole places and spaces, and consider how people, history, and places shift and change with time and perspective. Don’t forget to check back in next month for a new Seminole Spaces installment!

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

Blakney-Bailey, Jane Anne. An Analysis of Historic Creek and Seminole Settlement Patterns, Town Design, and Architecture: The Payne’s Town Seminole Site (8AL366), a Case Study. A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Florida. 2007.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Lakeland, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.