Seminole Spaces: Lake Okeechobee

Welcome to the next installment in our intermittent series on Seminole Spaces! In this series, we explore places and spaces important to Seminole history, culture, and tourism. This week, we are exploring the Seminole relationship with Lake Okeechobee, and how it has shifted and changed over time.

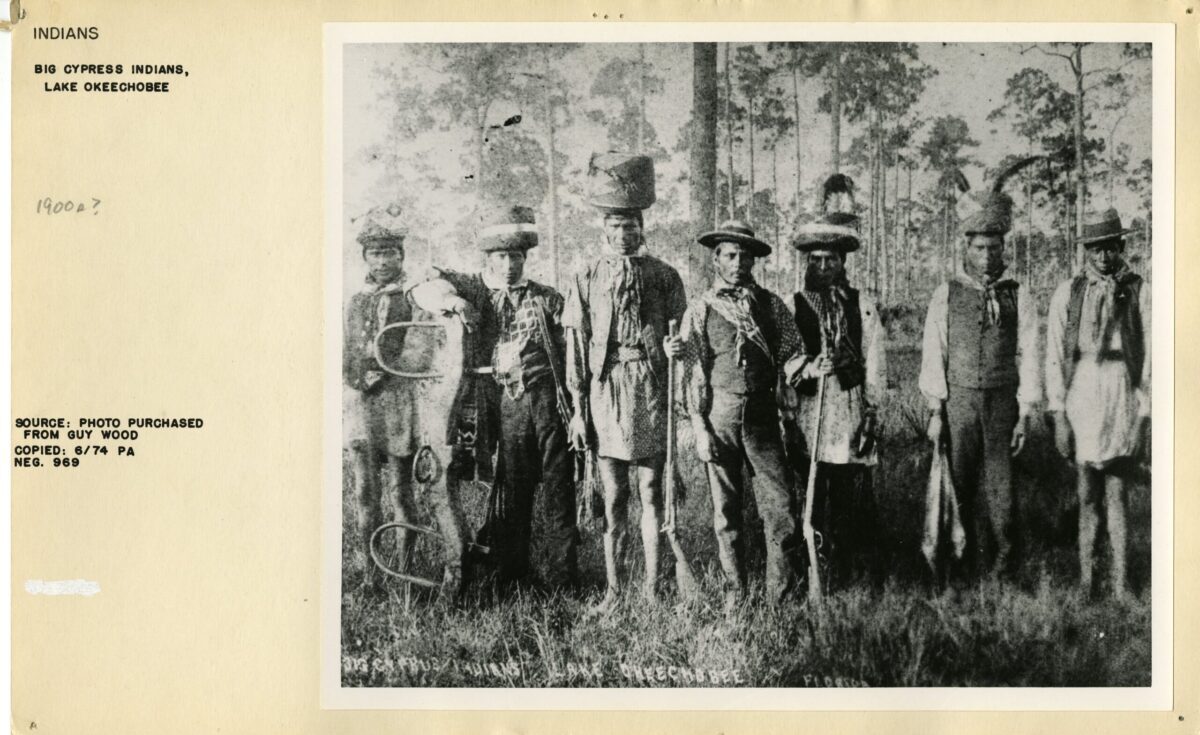

In this week’s featured image, you can see a photograph of a group of Seminole men standing in front of trees. They are wearing bigshirts, or suits. Some wear turbans, and several carry rifles. One, on the left, leans up against a double oxen yoke. According to the accompanying text, the photo was taken on Lake Okeechobee in the early 1900s.

Pre-1900

Lake Okeechobee is the largest freshwater lake in Florida, and the name comes from the Seminole words for ‘big water’. Water from the Kissimmee River, Fisheating Creek, Lake Istokpoga, and Taylor Creek would flow into Lake Okeechobee, which collected rainfall in its shallow basin. Water would then slowly spill south as it rose during wet season, replenishing the Everglades. It would feed the vast, slow-moving river of the Everglades, and support Florida’s famous River of Grass. This natural flow also helped make the Everglades one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world. Prior to intervention, grasses from the lake would naturally sink to the lake bottom. Periodically, this nutrient dense muck would make its way into the Everglades through floods or storms, flushing the lake of debris. As dry season progressed, the natural basin of Lake Okeechobee was a refuge for those seeking its most important resource: water.

The ever-changing and virtually unlimited boundaries of Lake Okeechobee prior to 1900 helped support the vast variety of plants and wildlife of South Florida. The edges of the lake were much more expansive, occupying an area of about 1,000 square miles. Today, the lake covers around 730 square miles, and is incredibly shallow. Lake Okeechobee’s average depth is only about 9 feet. It supported traditional Seminole life, who would use dugout canoes to effectively navigate these natural waterways, as well as hunt, fish, and live on its borders. Now, it is still an important wildlife resource, despite its shrunken state. Lake Okeechobee supports “Everglade Snail Kites, wading birds, waterfowl, Purple Gallinules, and myriad fish, frogs, snakes and turtles…few comparable remnants of wild Florida remain.”

Seminole Relationship with the Lake

Seminole ancestors and Lake Okeechobee have always been deeply intertwined. Prior to development, Lake Okeechobee fed vital waterways that supported rich hunting and canoeing areas. As we have noted in previous blog posts, water was the original highway of Florida. Seminoles could canoe virtually anywhere. In Patsy West’s The Enduring Seminoles, West writes the “effects of drainage were immediate and disastrous to the lifestyle of the Florida Indians…Their hunting, gathering, and visiting patterns, their maritime skills, and the innumerable other folkways were soon curtailed, altered, or lost for all time” (West 31). These drainage and canal programs, meant to tame the Everglades to encourage land-use like farming by new settlers, devastated Seminole hunting and travel routes and hastened the shrinking of Lake Okeechobee.

In 1952, Sam Huff spoke to anthropologist William C. Sturtevant about the drainage, saying “Just as soon as they hit Okeechobee the water was going to dry up. But, I didn’t believe it, until they hit Okeechobee. Then the water dried up, and even in Okeechobee it was dry too. The Everglades became small.” (West 31). The natural flow of Okeechobee to the Everglades was interrupted, and animal populations scrambled to adapt. In 1956, Pete Tiger related how that “In the old times we could paddle our canoes for many days and hunt the deer and the alligator. Now the white man has drained the Glades with his canals to make fields for his tomatoes and sugar cane. Our canoes cannot run on the sand and it is forbidden to cross the white man’s fences. And the deer and the alligator go farther away” (West 30).

Post-Drainage

Drainage began in the late 1800s through a series of canal projects. The United States Government, and other entities, envisioned a rich farmland for new settlers to populate. But, the ever-changing limits of Lake Okeechobee made the area marshy and unpalatable. In 1881, Hamilton Disston bought 4 million acres of land from Florida at 25c an acre. Disston dredged “11 miles of canals south of the lake, widening and deepening the Kissimmee River for navigation, and dug another canal connecting Lake Okeechobee to…the Caloosahatchee River” (Naples Daily News, 06 Mar 2006). The first to try to seize control of the waters of Lake Okeechobee, Disston drained 50,000 acres of Florida swampland around the lake. In 1905, Florida’s 19th Governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward would create the Everglades Drainage District. This would eventually result in the St. Lucie, Hillsboro, North New River, West Palm Beach, and Miami Canals.

2009.34.737, ATTK Museum

These drainage projects would spur settlement around the lake, enticing people with promises of rich farmland. Above, you can see a photograph of farm land along Lake Okeechobee. William D. Boehmer took this photo in July 1959. But, the vast water was harder to control than a few canals could manage. As more people settled the area, the need for more canals and drainage became increasingly apparent. In a 1922 Palm Beach Post article, Chief Drainage Engineer C. F. Elliot argued for the St. Lucie Canal. Elliot stated “As the territory along the drainage canals is developed, and as it becomes settled and cultivated, the necessity for local drainage increases; and as this necessity increases, so must the use of the drainage canals for lake control be reduced” (Palm Beach Post, 13 Aug 1922). The scramble to add more and more canals to prevent disaster became increasingly panicked.

Herbert Hoover Dike

In the 1920s, the powder keg created by piecemeal drainage projects and unfettered settlement would reach its explosion point. In 1926, the Great Miami Hurricane would hit Lake Okeechobee and kill 300 people. Only two years later, the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane would kill thousands. Both storms were marked by dangerous storm surge, where high winds brought water over the 6ft man-made dike that circled the lake at the time. This resulted in the largest intervention to the lake thus far: the construction of the Herbert Hoover Dike. The Herbert Hoover Dike is a 143 mile-long earthen dike surrounding the entirety of Lake Okeechobee. The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1930 “authorized the construction of 67.8 miles of levee along the south shore of the lake and 15.7 miles along the north shore.” The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would complete these levees between 1932 and 1938.

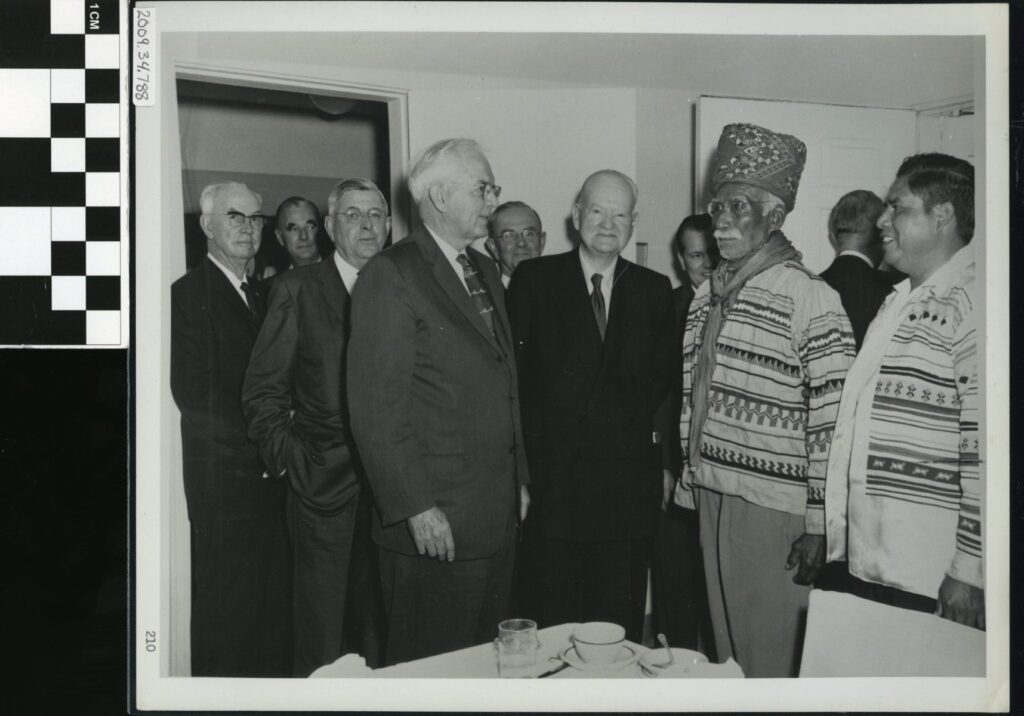

The Flood Control Act of 1948 expanded the dike, after another major hurricane in 1947 prompted the need for additional flood and storm control. They would complete the dike system in the 1960s, and named after Herbert Hoover. Hoover was instrumental in the dike construction. Below, you can see a photographic print of Billie Bowlegs meeting Herbert Hoover. In the foreground are Senator Spessard Holland, former President Herbert Hoover, Billie Bowlegs, and Billy Osceola; the others seen the background are not identified. The photograph was taken in Clewiston, Florida during events taking place for the dedication of the Herbert Hoover Dike surrounding Lake Okeechobee on January 12, 1961. The Herbert Hoover dike is “controversial. It is, depending on your point of view, a godsend or an offense against the very earth” (Palm Beach Post, 14 Sep 2003). For better or worse, the dike was here to stay.

The Great Frontier

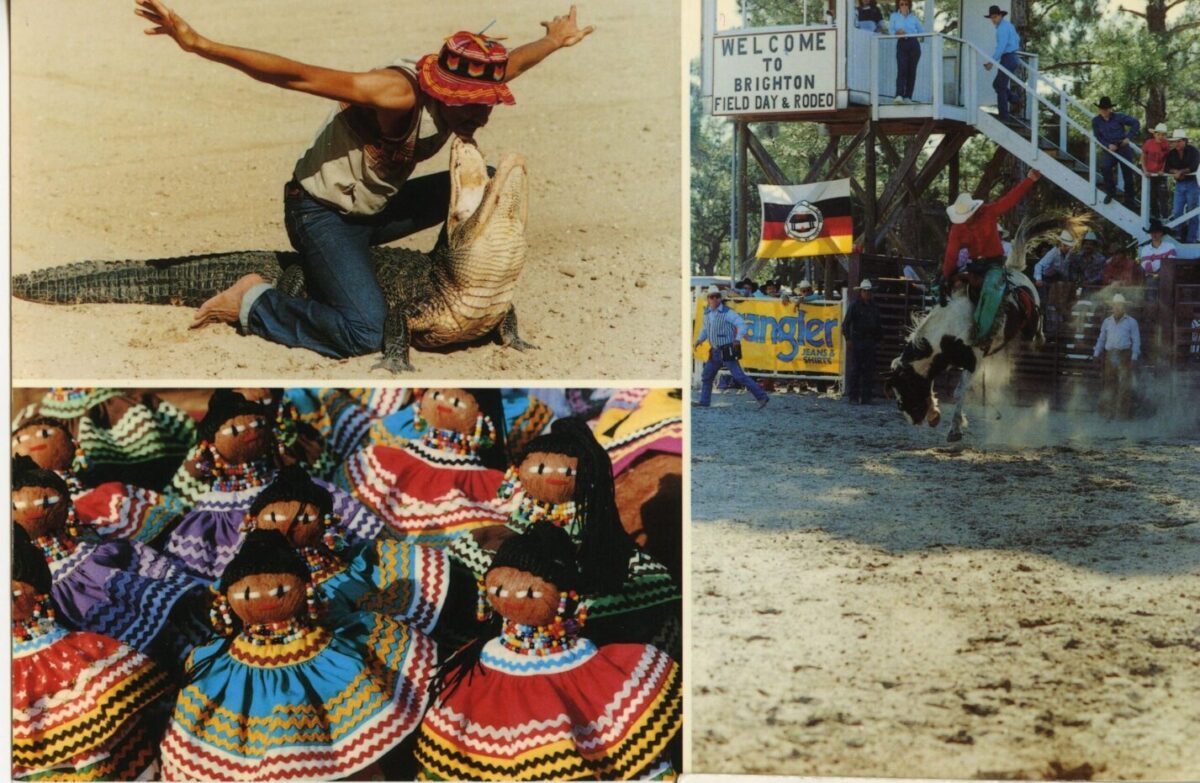

Lake Okeechobee has been a resource, meeting point, and place of fascination ever since the beginning. Even with the massive interventions of the last 150 years, it remains an incredibly important part of the South Florida ecosystem and an intriguing natural resource. People still flock to the lake, and this unique ‘inland sea’ provides ample opportunities for people to experience the real Florida. While historically it has been linked mainly to agriculture, in the more recent decades boating, fishing, and hiking have been popular past times linked to the lake. Lake Okeechobee also remains at the heart of Seminole community. The Brighton Reservation is located right on the northwest of Lake Okeechobee. The Big Cypress Reservation is located south of the lake.

2005.1.1732, ATTK Museum

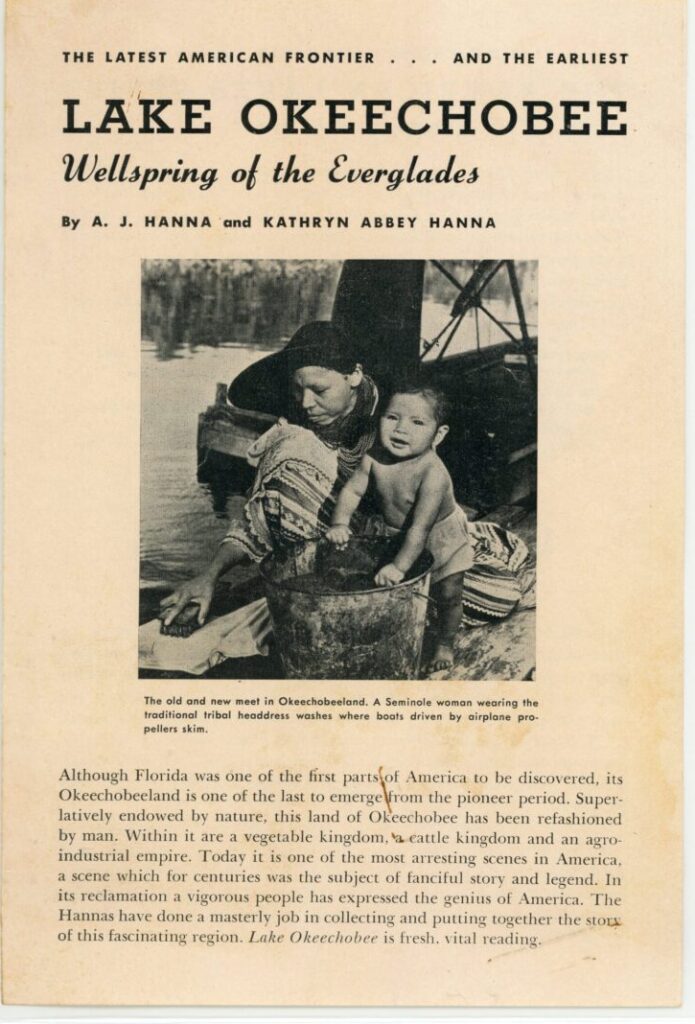

Above, you can see an ad for Lake Okeechobee, Wellspring of the Everglades which printed on November 15, 1948. A. J. Hanna and Kathryn Abbey Hanna wrote the piece. In it, it describes Lake Okeechobee as “superlatively endowed by nature…[and] refashioned by man.” Recently, efforts to restore and revitalize the water quality of Lake Okeechobee have been gaining more traction.

Previously in this article, we noted that the dike and canals impeded the natural flushing process of the lake into the Everglades. This resulted in an overgrowth of bacteria and debris material, causing the sandy-bottom lake to become muddy and toxic. This, along with atypical water flow, have negatively impacted water levels and quality. The Lake Okeechobee Watershed Restoration Project (LOWRP), part of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) seeks to rectify this damage. But, this high-risk project is controversial, and the possibly negative impacts on Seminole life and history can’t be ignored. The Brighton community, and the Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) remain wary of the project.

What can you see?

Lake Okeechobee offers several recreational activities for locals and visitors alike. Below are two great family-friendly options to get outside in this striking natural area. In addition to these two options, there are ample opportunities to go out and find your own exciting activities on Lake Okeechobee. We encourage you to explore these designated nature areas and enjoy this scenic and remote part of Florida!

Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail (LOST)

Part of the Florida National Scenic Trail, the Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail is a 115-mile trail along the Herbert Hoover Dike. The 35-foot vantage point atop the dike allows hikers the full beauty of Lake Okeechobee, as well as the agricultural beauty found in sugar cane and citrus fields. The Army Corps of Engineers maintains thirteen primitive campsites on the trail. There are a number of sites from the Great Florida Birding Trail along Lake Okeechobee, as well, so keep your eyes open!

Lake Okeechobee Battlefield State Historic Park

The site of one of the most significant battles of the Second Seminole War, the Lake Okeechobee Battlefield State Historic Park marries “public outdoor recreation and conservation.” The Battle of Okeechobee was fought on Christmas Day, 1837, and involved over 1,000 U.S. Military troops fighting against a few hundred Seminoles. The battle is considered a turning point in the Second Seminole War. Only a few Seminole perished, but more than 1/3 of the soldiers that had attacked the hammock were dead or wounded. This devastation to U.S. forces allowed vital time for the Seminole population to recede into the Everglades. The state park preserves and honors this important battlefield, and is an important place to visit when learning Florida, and Seminole, history. At the park birding, picnicking, and geocaching are popular activities. Annual Battle of Okeechobee reenactments occur the last week of February.

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

West, Patsy. The Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wresting to Casino Gaming, Revised and Expanded Edition. 2008. University Press of Florida. Digital.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.