Oh my Gourd! Seminole Pumpkins and Other Uniquely Cultivated Seminole Foods

Last month, we shared some sweet and savory Seminole treats and recipes that you can try at home. As we touched on previously, Indigenous cooking and harvesting represent acts of resistance to the pressures of colonization. Therefore, it is increasingly important to recognize, uphold, share, and support Indigenous cooking methods, patterns of subsistence, and what they represent. This week, we will look at several uniquely Seminole cultivated foods, and how they became important staples in the Seminole diet. We will look at Seminole pumpkins, coontie, and cabbage palm, as well as how Seminole gardens were uniquely designed to thrive in the Florida ecosystem and hide their important food resources.

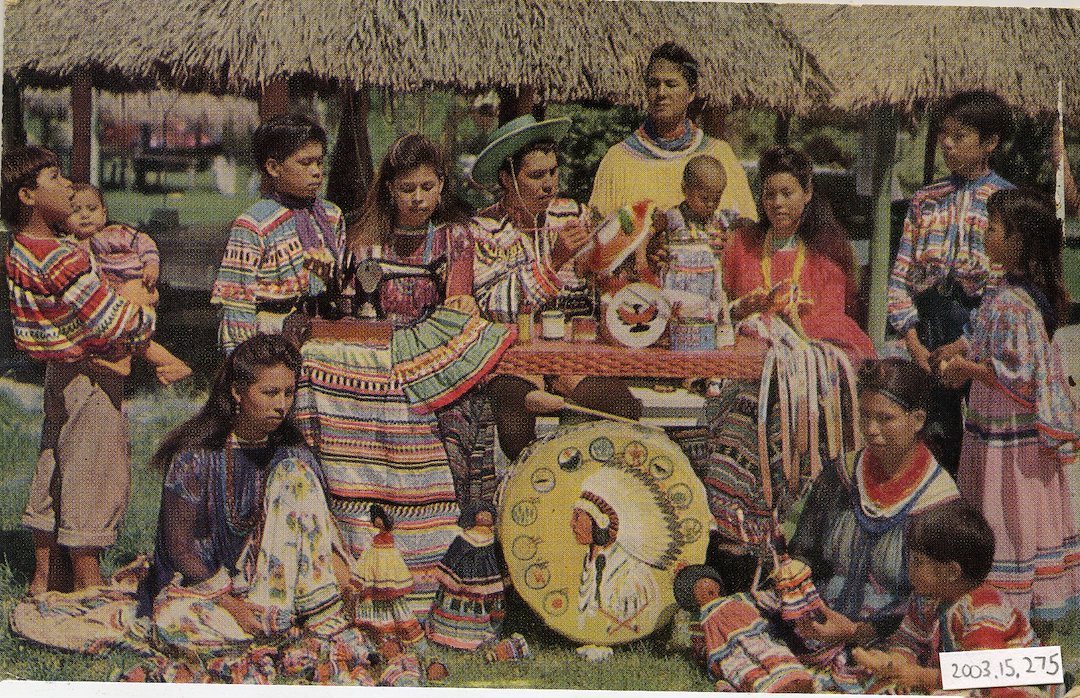

In our featured image this week you can see corn planted in a Seminole camp, probably early to mid 20th century. You can see chickees around it in the background (2007.46.27, ATTK Museum). Below, you can see a Seminole pumpkin.

Wikimedia Commons

Seminole Foods

Although Florida is a harsh and wild environment, Seminole subsistence patterns show that there is always an abundance of food for those willing to cultivate, forage, and hunt for it. Foraging, gardening, and hunting are all important facets to Seminole foodways. Interestingly, Seminoles also did not adhere to a strict three-meal-a-day schedule. Alanson Skinner, mentioned in the previous post about Seminole foods, would observe that “food, generally sofki [sic], venison, biscuits, or corn-bread, and coffee, is always ready for the hungry. Twice a day, in the morning and evenings, Seminoles have regular meals, but eating between times is a constant practice” (Skinner 70). But, that does not mean it isn’t hard work! Living off the land is time consuming, and takes a large amount of generational knowledge. One strong example was during the Seminole War period, when generational knowledge of how to harvest and process coontie helped Seminoles to survive.

Seminoles depended on a healthy ecosystem to eat. Eating, therefore, is a community and family-centered activity. Not only in the eating, but in the preparation, harvest, and collection of these foods. From harvesting, hunting, or foraging to preparation, each step is a cultural celebration. Seminoles tie food closely with the environment, and what is available and abundant. It gives new meaning to the phrase “Eat local!” Thus, Seminoles ate a wide variety of native plant and animal species. Fish (including gar, catfish, pickerel, bass, and many other species), deer, turtle, alligator, and even the occasional manatee were all part of traditional Seminole foods. Pumpkins, watermelon, corn, pond apple, citrus, beans, cabbage palm, and other hardy vegetables were common staples.

Seminole Gardens

Seminoles often planted gardens, although they typically didn’t resemble the rigid, orderly gardens we think about today. In our previous post about Seminole foods, we discussed Seminole gardens with the Tribal Historic Preservation Office’s Research Coordinator, Dave Scheidecker. Scheidecker stated that gardens would “always be in a hammock separate from where they lived, up to a mile away.” This reduced the chances of food being compromised, and offered Seminoles protection during the Seminole War period. “One (hammock) for living, one for the garden,” meaning that if “someone finds one, you still have the other.” Often, Seminoles disguised their gardens to look like natural growth. This was a response to the increasing pressures on Seminole people during and before the Seminole War period. U.S. troops destroyed Seminole gardens if they were found, resulting in a tragic loss of food for the remaining Seminole resistors.

Cultivated gardens were therefore incredibly important to the Seminole food system, and closely tied to their safety and security. In Florida’s harsh environment, food insecurity was incredibly dangerous. Traditionally, these “gardens played a key role in the camps. Seminoles grew beans, sweet potatoes, pumpkins, melons, and other produce within the camps themselves; corn and sugarcane grew outside the camp in other hammocks” (Dilley 84). Gardens planted in other hammocks were protected from prying eyes, as you would not be able to see through the thick foliage into the hammock. Seminoles regularly utilized hammocks for gardens through the 20th century, and the remnants of these gardens can still be seen today.

Seminole Pumpkins

Florida’s first people cultivated Seminole pumpkins, which are heirloom variety squashes. A cultivar of Cucurbita moschata, Seminole pumpkins are closely related to butternut squashes and calabaza. Smaller and squatter than traditional pumpkins, the flesh is similar in taste to butternut squash. Both the flowers and the squash are edible, and mature Seminole pumpkins can reach around 12 lbs. The flowers can be eaten raw, stuffed, or even fried! Unlike “jack-o-lantern” pumpkins, Seminole pumpkins come in a variety of shapes and colors, and are often cross-pollinated with other squashes. Typically, they are rounded with very pale, dull orange flesh. The inside flesh is sweet. In most parts of the state, they can be planted any time between August and March. They also seem to thrive on neglect and are considered an exceedingly low-maintenance vegetable.

What makes Seminole pumpkins special is their unique qualities that make them perfectly suited for the Florida environment. With evidence that Seminole pumpkins in Florida predate Spanish contact, Seminole pumpkins are well adapted to Florida’s wild environment. Today, you can find Seminole pumpkin seeds at seed exchanges throughout the Southeast. These special squashes are naturally resistant to pests, and are incredibly resilient in the hot and humid summer environment where other pumpkin varieties may rot (23 Oct 2019, Port Charlotte Sun).

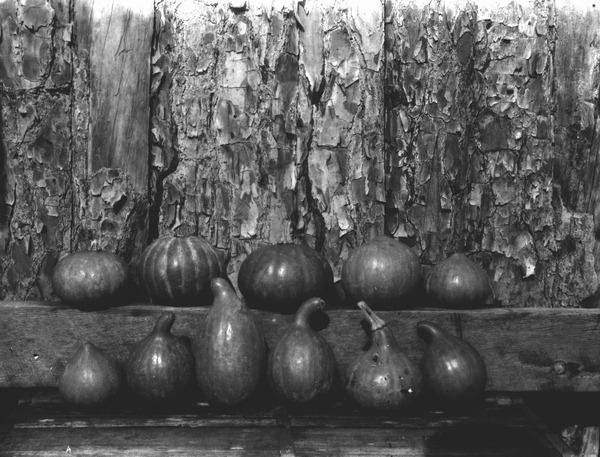

In fact, Seminole pumpkins appear to thrive in Florida’s wet and swampy weather! Seminole pumpkins also store well; they can be stored for up to a year if stashed in a dry location with plenty ventilation! All of these qualities made them ideal for Seminoles, who were able to plant and cultivate large amounts of pumpkins with relative ease. Below, you can see several Seminole pumpkins lined up against a wooden backdrop in 1929.

Small, State Archives of Florida

Hanging Pumpkins

Although they can also be grown on the ground, Seminoles were known to trellis their pumpkins and grow them vertically! They would plant the pumpkins at the base of a dead tree. Often, Seminoles would girdle a tree specifically for this reason. The vines would quickly grow up the tree and across the branches, allowing the fruiting pumpkins to hang down (26 Oct 1997, The Stuart News). This growing practice was another way Seminoles could protect their food, and hide an entire garden of pumpkins in the canopy. In swampy Florida, burying food was not really an option. So, being able to grow the pumpkins high up in the canopy was incredibly useful. The pumpkins could even be stored on the vine in the trees, as the vine would die into the winter months. This method of growing Seminole pumpkins was incredibly high yield, allowing for robust food stores.

Also known as “Chassa howitska” (the Miccosukee word for ‘hanging pumpkin’), the Seminole pumpkin has recently been making a comeback with home gardeners. An heirloom variety with a rich history, many are trying to bring this particularly unique cultivar back into common rotation. Despite being small, many note that the Seminole pumpkin is incredibly sweet and delicious, with a unique depth of taste making it a quick favorite. Patrick D. Smith, who wrote A Land Remembered, noted in 1987 that “This is absolutely the very best pumpkin that we have ever eaten!” (21 Jan 1987, The Naples Daily News) Interested in planting some Seminole pumpkins of your own? This low-maintenance squash needs a lot of room to roam, with the vines stretching out across your garden. We encourage you to try planting Seminole pumpkins in your own gardens, and help bring back one of Florida’s native squashes!

Coontie

Have you ever heard of coontie flour? A labor intensive traditional Seminole staple, coontie flour is made from the Zamia plant. It is also incredibly poisonous when not prepared properly! A shrubby plant with a tuberous root system, the zamia plant contains cycasin, a poison which effects the gastrointestinal and nervous system. Ingestion can lead to liver failure and even death. Thus, in order to utilize it as a food stuff, the cycasin needs to be leached away. This is a long process that requires incredibly specific knowledge to get correct! The roots were peeled and washed, and stored between dried palm fronds. Then, each root was grated and rinsed. Below, you can see a Seminole woman using a coontie grater, date unknown.

2013.29.6, ATTK Museum

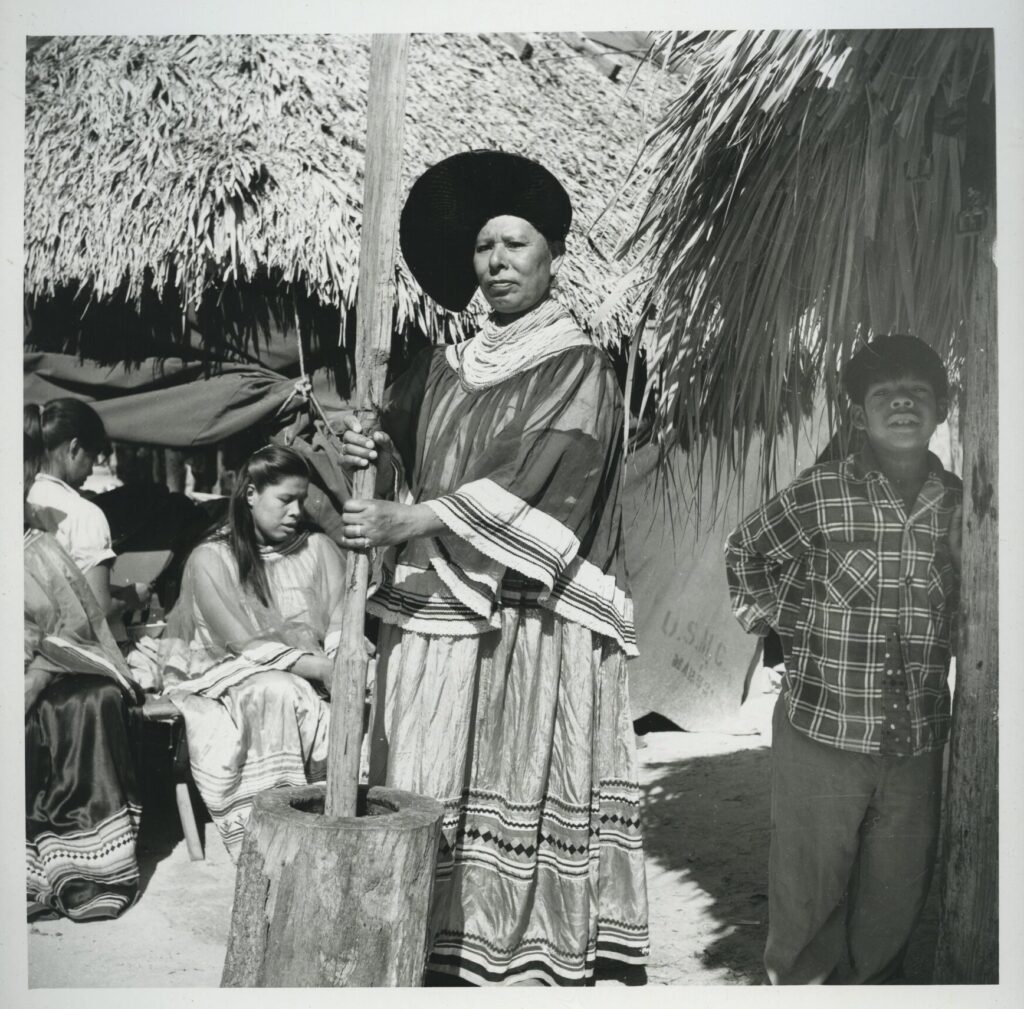

Then, they would pound it into a pulp. Seminoles ground both coontie and corn flour with a wooden mortar and pestle. Below, Lena Gopher grinds corn with a typical mortar and pestle. Behind Lena is Agnes Huff Jumper and to the right, leaning on the chickee post, is Roy Rogers Huff. William D. Boehmer photographed the scene in 1960. Corn was also an incredibly important Seminole staple. Seminoles would rinse the resulting coontie pulp many, many more times. Then, they strain and dry it to ensure all the cyasin had been leached out.

Once processed, the coontie flour was used in a variety of foods, including both a flat, round bread as well as sofkee. In particular, coontie flour represents a generational well of inherited knowledge, as well as a deep connection with the environment. It also represents Seminole resilience, as it was incredibly important during the Seminole War period. Coontie flour helped Seminole survive incredibly pressure from the U.S. Army forces, who routinely tried to sabotage their food stores.

2009.34.1631, ATTK Museum

Cabbage Palm

Cabbage palm is one food that you’ve probably already had – and you didn’t even know it! You find it in the grocery store as ‘hearts of palm’. The delicate heart of the sabal palm (Florida’s official state tree!), swamp cabbage is both plentiful and versatile. The heart is a creamy white color, and very tender. You eat it raw in a salad or stewed with salted pork or sugar. Seminoles strip away the tough outer leaves with a machete or hatchet. With a little bit of work, you have a tender and delicious side dish or addition to any salad. Sabal palms are so abundant that they don’t require any cultivation. Thus, foragers can easily find swamp cabbage throughout the state of Florida. Looking for a recipe? Try this one from the Seminole Tribe of Florida!

Even now, in our modern world, it is important to support native plants and Indigenous subsistence patterns. This November for Native American Heritage Month, we encourage you to explore some of these traditional Seminole foods. Try some fry bread, search out some Seminole pumpkins, or pick up some local swamp cabbage! You can read first part of this Seminole foods series and get some recipes to try here in a previous post. Happy eating!

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

Dilley, Carrie. Thatched Roofs and Open Sides; The Architecture of Chickees and Their Changing Role in Seminole Society. 2018. University of Florida Press. Digital.

Skinner, Alanson. “Notes on the Florida Seminole.” American Anthropologist, vol. 15, no. 1, 1913, pp. 63–77.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.