How Does Your Garden Grow? Food Sovereignty and Security

Food is deeply connected to culture, family, and our relationship with the world. But beyond nourishment, food can also serve as an act of resistance. While it may seem simple, what you eat, how much you eat, and how you access food are all shaped by complex and layered systems.

For Indigenous peoples, survival itself is an act of resistance. Throughout history, they have faced violence, oppression, forced relocation, and attempts to erase their culture. In this context, choosing to survive, to maintain cultural practices, and to stay connected to community are powerful, anti-colonial acts.

So how does this relate to gardening? How can the simple act of planting something be an act of resistance?

This week, we explore Seminole gardens, past and present, through the lens of resistance and survival. Although the challenges faced by Indigenous communities today differ from those of the past, cultivating traditional foodways remains a vital and resilient form of cultural preservation and resistance.

Gardens during the Seminole War

During the Seminole War period, access to food was tightly tied with safety. U.S. soldiers were actively pursuing Seminoles and pushing them deeper into the Everglades as the wartime period wore on. Seminoles who were captured were forcibly transported north and then abandoned on reservations with poor soil. If, that is, they made it that far. Due to all these hostile pressures, trading with even trusted Americans was a huge risk. Most of their foodstuffs had to be things they could hunt, forage, or cultivate. Thus, Seminoles often planted gardens to support their families and communities.

But Seminole gardens didn’t look like what we would typically think a garden would look like today. Seminoles would clear land within a hammock (also known as a tree island) where they could be protected and hidden. Due to the landscape of the hammock the gardens would not be visible from the outside. Hammocks also form on slightly higher ground, meaning they would be less likely to flood even in the wet season. Soldiers passing by would not be able to see the gardens. This made it less likely for the community or the food to be discovered.

In a previous blog post the Tribal Historic Preservation Office’s Senior Research Coordinator Dave Scheidecker spoke to us about typical gardens during this period. Gardens would “always be in a hammock separate from where they lived, up to a mile away” states Scheidecker. “One (hammock) for living, one for the garden.” This meant if “someone finds one, you still have the other.” Hammocks were regularly used for gardens up through the mid-20th century for protective purposes. Seminole gardens were then closely tied to safety and security. Not only could the loss of a garden expose an entire community, but food insecurity at that level could be incredibly dangerous in Florida’s harsh environment.

What is in a Seminole garden?

A typical Seminole garden would be stocked with pumpkins, tubers, corn, beans, citrus, melons, and other hardy vegetables. Seminole pumpkins, which are hardy heirloom squash, are particularly adapted to the Florida environment after centuries of breeding. They have thick shell-like skin to trap water, and a similar taste to a butternut squash. They can be a variety of colors and weigh up to 12 pounds.

Often cross pollinated with other squashes, Seminole pumpkins could be grown vertically. This earned them the name “hanging pumpkins.” Seminoles would girdle a large tree, and the vines of the plant would climb the branches with the fruit hanging down from the canopy. These pumpkins were also incredibly low maintenance and could be abandoned and still thrive. The flowers are also edible, and can be eaten fried, stuffed, or raw. Items like corn could be made into sofkee or bread.

Seminole gardens would not follow the same rigid, row-based design that we imagine gardens to have. Often, they would be planted in a way that is intentionally visually haphazard. This is an additional layer of protection. Even if someone were to stumble across and into the hammock, they might not even realize they were standing in the middle of someone’s garden! After the wartime period “gardens played a key role in the camps. Seminoles grew beans, sweet potatoes, pumpkins, melons, and other produce within the camps themselves; corn and sugarcane grew outside the camp in other hammocks” (Dilley 84).

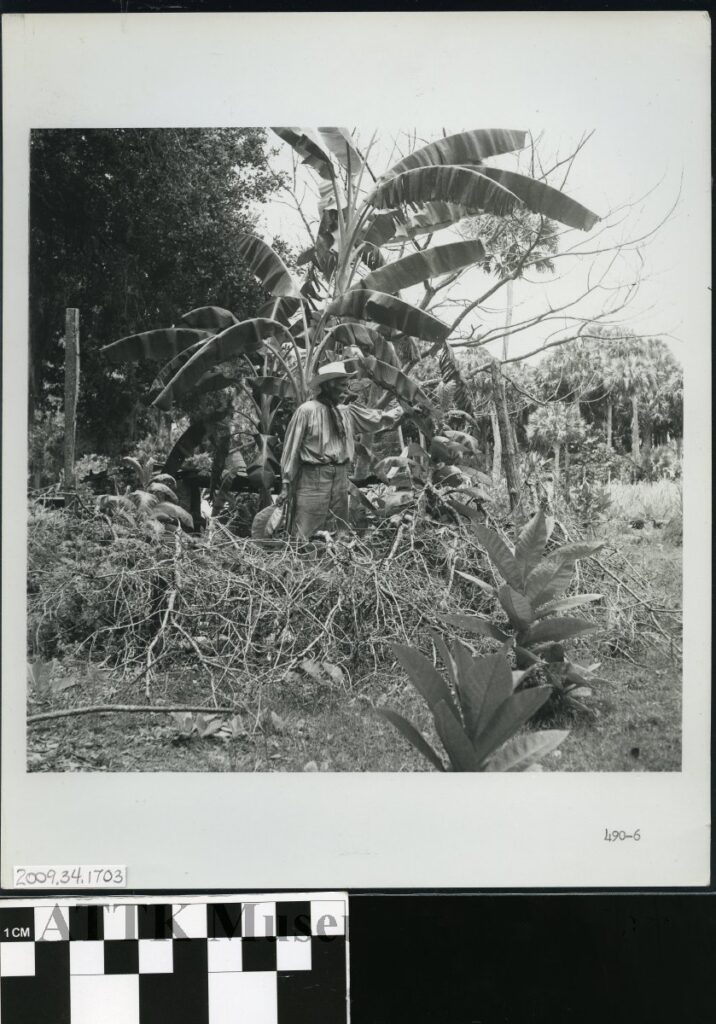

Gardens were also important community and family touchstones. The preparation, planting, harvesting, and storage of these foods was a community activity, tying everyone together even more tightly. Below, you can see Billy Bowlegs III with his tobacco and banana plants. Bowlegs always had a robust garden and grew “sweet potatoes, sugar cane, squash, and corn.” Notice in this image the “bramble bush” protection for the bananas.

2009.34.1703, ATTK Museum

Foraged Foods

Another way that resistance and resilience is folded into traditional Seminole food pathways is through the connection to the land. Seminole foods are intimately connected with the environment and geographic space. Many traditional foodstuffs were foraged foods. Seminoles didn’t plant and grow them per se, but lived off of the bounty of the Everglades. Things like swamp cabbage and coontie are particularly important examples.

Swamp cabbage, also known as hearts of palm, is the inner flesh of a cabbage palm. Seminoles strip away the tough outer bark with a sharp knife or machete. It is both plentiful and versatile, and you can eat it both raw and stewed. Foragers can easily find sabal palms throughout the state of Florida, making them food that could be found anywhere. This would have been especially useful when moving from camp to camp in order to evade soldiers.

Coontie flour is made from the zamia plant and is incredibly poisonous if not processed properly. The zamia plant contains cycasin, a poison which impacts the gastrointestinal and nervous system, and can lead to liver failure and even death when ingested. In order to make it edible, the cycasin needs to be leached away.

Seminoles perfected this process, which takes incredibly specific knowledge to get correct. The roots are peeled and washed, then stored between dried palm fronds. The tubers would then be grated and repeatedly rinsed and pounded into a pulp with a mortar and pestle. It would be rinsed many, many times before being strained and ground again into a flour. Once processed, the flour could be used in a number of ways including in bread and sofkee.

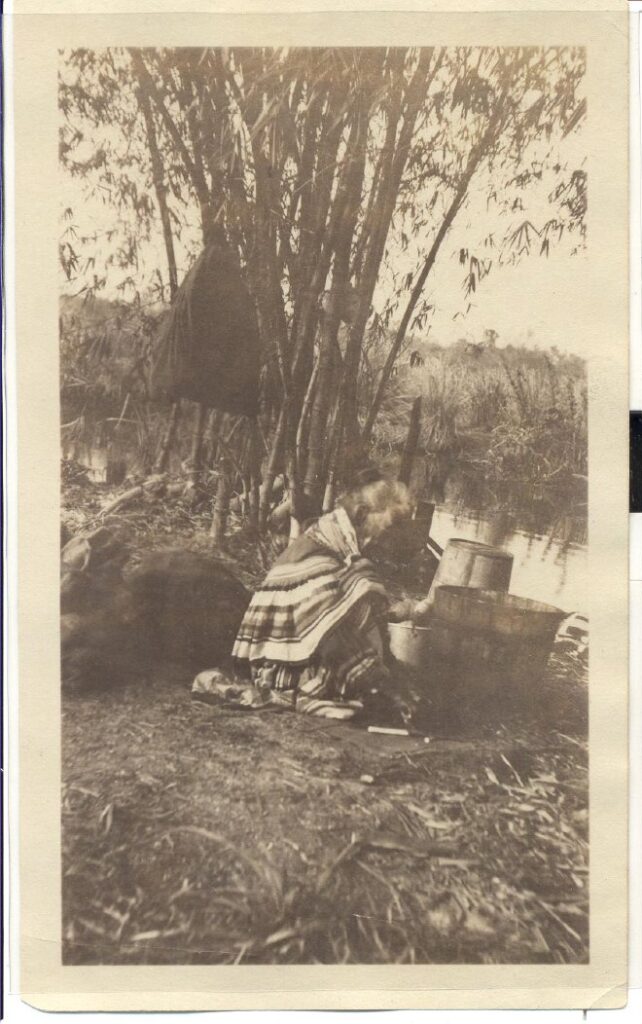

Cabbage palm and coontie are strong examples of how Seminole food traditions are rooted in resistance. Both require deep generational knowledge to harvest and process, and both were traditionally foraged in the Everglades by those who knew where and how to find them. This ability to gather food from the land helped protect the Seminole people from food insecurity, especially during times when U.S. soldiers would destroy any food stores they discovered. Below, you can see a photo from 1923 of a Seminole elder washing coontie tubers, illustrating this traditional practice.

2004.27.1, ATTK Museum

What is Food Sovereignty?

During the Seminole War period, gardens were an active part of Seminole survival, and thus an act of defiance and resistance against colonialism. Today, Seminole gardens and Indigenous food pathways still represent an act of resistance, albeit in a different way. Gardens are now a way to stay rooted in culture, prioritize Indigenous ways of eating, combat climate change, and decouple eating from Western colonialism. They represent a step towards food sovereignty.

According to the U.S. Food Sovereignty Alliance, food sovereignty “is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” Breaking this down, it prioritizes not only sustainable and culturally relevant foods but also places control back into the hands of the individual and the community. Rather than being beholden to larger, overarching corporations, food is localized, and power is in the hands of the harvester.

The Ahfachkee Traditional Garden

Tended by students every day, the Ahfachkee Traditional Garden is located on school grounds on the Big Cypress Seminole Indian Reservation. The large garden is stocked full with many traditional Seminole crops, and students learn how to plant, care for, harvest, and process the food with direction from traditional preservation program instructors.

The mission behind the garden is two-fold: connect students to their traditional food pathways and instill in them the skills and knowledge they need to have their own gardens when they are adults. Instructors begin bringing the students in pre-K, so that by the time they graduate they have the confidence to plant and take care of their own garden. “Being able to plant something and see it grow is exciting for them,” said Maxine Gilke, traditional preservation agricultural instructor, said in a Seminole Tribune article. “They put their time and effort into it and get to see something grow.”

Some of the produce grown in the garden includes: avocado, banana, carrots, celery, cabbage, chayote, coconuts, collards, corn, eggplant, garlic, green beans, lemongrass, limes, onions, mango, mint, okra, papaya, pigeon peas, peppers, sweet potatoes, white potatoes, scallions, sugar cane and tomatoes.

There is also a robust traditional plant inventory, including: aloe, coontie, assorted medicine plants, wild hibiscus aka ‘Seminole candy’, strawberry leaf plant and potatoes found in the roots of elephant ear plants. Many of the plants come from elders in the community. Jeanette Cypress, Ahfachkee’s traditional preservation program director, shared that wild hibiscus is a particular favorite. “I hadn’t had wild hibiscus since I was a kid,” she said. “A few years ago, we found some growing wild and planted one at school. Now it grows everywhere.”

Compost made from cafeteria scraps is used to fertilize the soil, with help from the high school science program that takes care of the compost. In turn, Horacio Smith, cafeteria manager, often uses the produce to feed the school. On Fridays, high school students also cook a meal with the garden’s spoils in the culture chickee. This unbroken cycle of planting, nourishing, harvesting, eating, and planting again is one of the core aspects of food sovereignty. It also sets up the next generation with the skills they need to have control over their own food.

Prioritizing traditional foods brings those same students in contact with their own cultural foodways and centuries of knowledge. Gardens like the one grown at Ahfachkee are an incredible example of resistance through action. Student Ramona Jimmie stated plainly the impact of the garden, saying “We have to work together and know what is going on. It teaches us how to live and go back to our roots. It’s a good experience.”

Below, Ahfachkee traditional preservation agricultural instructor Maxine Gilke shows Allie Billie and other students how to harvest collard greens on March 10, 2020.

Photo by Beverly Bidney via the Seminole Tribune

The Big Cypress Community Garden Opening

Within the last decade, a renewed focus on food sovereignty has become a priority within the Seminole Tribe of Florida community. This has nourished not only the Ahfachkee Traditional Garden, but also another garden on Big Cypress. Marty Bowers, a Big Cypress Reservation resident, is the driving force behind the Big Cypress Community Garden.

Big Cypress exists in a food desert, with fresh produce and other items not readily available on reservation. He went to the Native Connections advisory board, a division of the Seminole Tribe’s Center for Behavioral Health, with his dream. “I’ve had this vision since 2018 of a thriving garden and community members with their hands in the dirt,” said Bowers. “We have the capability to feed our tribe.”

The “Let’s Be Trees” Garden would open on February 8, 2023. When it began it consisted of 40 raised garden beds, as well as an area for seniors and the “three sisters” area where corn, beans, and squash would grow together. The Native Connections board, which Bowers is a part of, monitors the garden, and provides supplies, seeds, and other necessary items for its maintenance and growth. You can see a mural painted by Ahfachkee students that is located next to the “three sisters” in our featured image this week.

While the physical garden itself is important, the community buy-in is equally important. “We have unity and community working on something together,” said Gherri Osceola, Native Connections tribal community support specialist. “Participation and involvement is our number one priority. We want to make it easy for them to be involved.” Monthly workshops are open to the community and focus on gardening, climate resiliency, health, nutrition and fitness. Bowers described the garden and community as an organic network. “I see the community like that; they can help each other grow and thrive,” he said. “What someone lacks, I may be able to help. If they are abundant in bliss, I may be able to join in that bliss.”

One Year Anniversary and Beyond

In June 2023 Bowers organized a trip to the Haudenosaunee Confederacy to learn more about food sovereignty with seven members of the United South and Eastern Tribes (USET) and the Climate Resiliency and Native Connections departments. This resulted in an invitation for a three-day cultural exchange with the Seminole Tribe of Florida, which coincided with the one-year anniversary of the “Let’s Be Trees” opening. “We went to their farm and garden to learn,” Bowers said. “They have five years of food put away and are bringing back centuries old varieties of corn. To them it’s about connecting to the earth mother and human community. Their message moved me.”

The celebration was attended by “tribal members and guests from the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, Cherokee, Dine and Osage Nations.” During the event traditional Seminole foods were cooked alongside items like “Osage grape dumplings, Onondaga venison with blueberry sauce and Mohawk red corn mush with strawberries.” Tuscarora white corn from the Onondaga Nation’s long-term seed preservation program was planted in a brand-new plot in the garden. The corn was a gift of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, which consists of the Cuyaga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga and Seneca tribes from upstate New York and Canada.

Bowers emphasizes the importance of the garden and the community, as well as his hope that the youth stay connected to the garden. “I’d like the entire community to see that growing food is meaningful,” Bowers said. “We are following the footprint that our ancestors put down. They had a path and we’re walking it. Soon we will see a field of corn growing in the middle of the community, which was probably how it used to be. This garden is magical.”

Today, Bowers still diligently tends the “Let’s Be Trees” Community Garden, which just recently held its first Garden Activity Day on September 4th. Community members familiarized themselves with “propagation boxes” and started seeds for the upcoming fall planting season. Over the summer, Bowers planted banana and citrus trees. He also worked to set up new trellises for the beans.

Tribal Members are welcome to join Bowers at two upcoming “Let’s Be Trees” Community Garden Activity Days on October 2nd and November 5th. On November 5th they will be collaborating with Integrative Health to share nutrition information and for a cooking demonstration. Please reach out to Marty Bowers for more information and other upcoming dates.

Additional Resources

Dilley, Carrie. Thatched Roofs and Open Sides; The Architecture of Chickees and Their Changing Role in Seminole Society. 2018. University of Florida Press. Digital.