Christmas 1837: Seminole Survival and the Battle of Okeechobee

Welcome back to our Seminole Spaces series! In this series, we explore the places and spaces important to Seminole history, culture, and tourism. This week, we are looking at a particular historic moment and space that changed the course of Seminole history, and highlighted their resilience, drive, and sacrifice to stay in their ancestral homeland: the Battle of Okeechobee.

In our featured image this week, you can see an oil painting titled “Battle of Okeechobee” by famed Florida painter Guy LaBree. LaBree was a longtime painter of Seminole legends, history, and culture and dedicated his craft towards meticulously accurate representations of the Seminole experience. You can learn more about LaBree and his close ties with the Seminole Tribe of Florida in a previous blog post.

Okeechobee Battlefield Historic State Park and the annual Battle of Okeechobee Reenactment

The Okeechobee Battlefield Historic State Park is located in a portion of the Okeechobee Battlefield. The Okeechobee Battlefield was acquired in 2006 with funds from the Florida Forever program. It is managed “to preserve lands of state and national significance, interpret the battle and provide living history events for Florida residents and visitors.” For many, it incredibly important to keep this history alive. Annually, there are living history reenactments of the Battle of Okeechobee in order to educate and share the history with the greater community and the next generation. Learning about the Seminole Wars is also an important part of Seminole youth education and built into the curricula. Next year’s Battle of Okeechobee reenactment will be held the last weekend of February 2024. Below, you can see an image of Seminole reenactors during a Battlefield of Okeechobee reenactment.

GRP1560.012, ATTK Museum

The Second Seminole War

Although the history books split the conflicts between the US and Seminoles into three wars, the reality for the Seminole people is they were embroiled in one, long war. For the Seminole, the war began when they came under organized attack by the US in 1812, and only ended in 1858. These decades of conflict were devastating and bloody, resulting in the death and removal of all but a few hundred Seminole.

The Second Seminole War, as termed by historians, began with the Dade Massacre in 1835. In 1832, several Seminole leaders were coerced into signing the Treaty of Payne’s Landing, agreeing to the relocation of the Seminole people to present-day Oklahoma. While some did go, many Seminoles refused this forced relocation, choosing instead to fight for their homes and ancestral lands.

On December 28, 1835, 107 officers and men under the command of Brevet Major Francis Langhorne Dade were making their way to Fort King near Ocala. Fifty miles shy of their destination, they were attacked by a contingent of 180 Seminole warriors in the pineland forest. The battle was brutal, with only three soldiers left alive. This spark ignited rising tensions between Seminoles, American settlers, and US troops that would continue through the end of the Seminole War period.

The Second Seminole War was the bloodiest and costliest of the three wartime periods, resulting in both the most casualties and the most expensive campaigns. The Second Seminole War would “end,” according to history books, in 1842. This supposed peace would not last, and again the US government would work towards Indian removal during the Third Seminole War (1855-1858).

Christmas Day 1837

186 years ago, on December 25, 1837, a group of around 400 Seminole warriors would go up against 800 US Army soldiers led by Colonel Zachary Taylor. Outnumbered 2:1 the Seminole resistors managed to hold their own, losing only 11 warriors and leaving 14 wounded before escaping. Seminole leaders Alligator, Billy Bowlegs, Abiaka (Sam Jones) and the recently escaped Coacoochee would command a group of fierce guerilla fighters for the Seminole side, against Colonel Zachary Taylor’s rigid military command.

Colonel Taylor would choose to employ a frontal assault against the Seminole forces, a choice that would cost him dearly. At the end of the day, the Seminoles would escape the battlefield, and continue their efforts of resistance against Indian removal. Zachary Taylor would go on to claim victory, although the reality was much more complex. At the Battle of Okeechobee reenactment in 2015, Gary A. Poe with the 8th Florida Company C reenactors would put it simply; “It was never a win or a loss. It was just a terrible battle.”

The Narrative

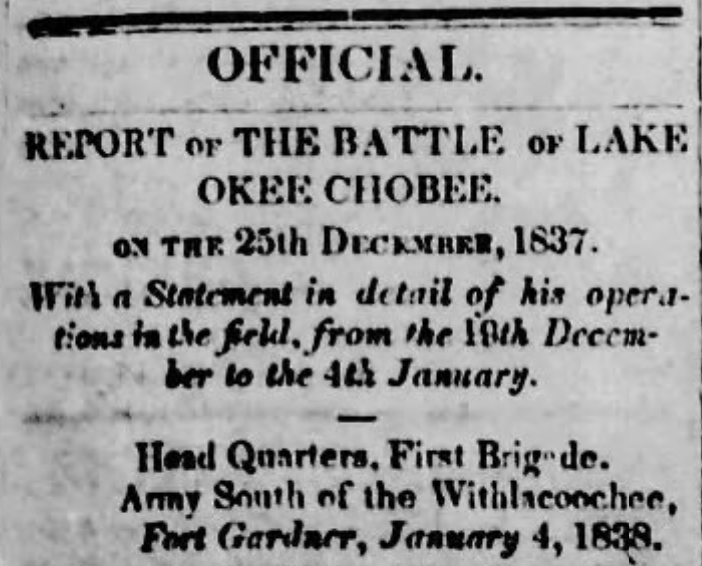

Immediately following the battle, the US seized the narrative around its outcome. Colonel Zachary Taylor’s account was published in full in the Southern Advocate on March 16th, 1838. Taylor penned the account only days after the event, which was then disseminated to the masses (below). In it, you can read the overwhelming spin from the US side as to not only the outcome of the battle itself, but the framing around it. Taylor and his regiments searched for the Seminole force, each time reaching a place where “the troops were again disposed of in order of battle, but we found no enemy to oppose us.”

Although not outlined explicitly by Taylor, the Seminole leaders were clearly orchestrating a best-case-scenario for themselves, driving the US forces into the swamp where the US would be unable to employ their rigid military tactics and were unfamiliar with the environment. Taylor himself describes how they “captured” a Seminole warrior a day before the battle, who conveniently did not put up a fight and pointed them towards the eventual battlefield site.

The Southern Advocate, 16 Mar 1838

Once the battle commenced, this framing continued. Taylor stated: “The action was a severe one, and continued from half past twelve until after three p.m. apart of the time very close and severe. We suffered much, having twenty six killed and one hundred and twelve wounded, among whom are some of our most valuable officers. The hostiles probably suffered, all things considered, equally with ourselves, they having left ten dead on the ground.” Immediately following this statement, he described the Seminole force as “completely broken.”

In describing his own losses and wounded, Taylor espouses their heroics, saying “there lay one hundred and twelve wounded officers and soldiers, who had accompanies me on hundred and forty five miles most of the way through unexplored wilderness, without guides, who had so gallantly beat the enemy, under my orders, in his strongest position, and who had conveyed back through the swamps and hammocks, from whence we sat out without any apparent means of doing so.”

The Reality

Taylor’s account of the Battle of Okeechobee builds a framework around the battle that would drive public and political perception beyond the Seminole War period. Repeatedly, Taylor uses language that frames the narrative, calling his own troops “gallant”, and the Seminoles “hostiles” and the “enemy.” He describes it in such a way that the Seminoles are placed as the aggressors, despite the fact that they were being pursed quite explicitly by Taylor and his forces. It is also missing from Taylor’s narrative that the Seminole side was overwhelmingly outnumbered 2:1.

He describes instead the US side at the disadvantage, stating that the Seminoles were at their “strongest position” and repeatedly underlining the harsh environment and hardships the US soldiers endured in their pursuit of the Seminoles. Taking Taylor’s account at face value, then, the average reader would draw from his words that the US side not only won the battle but did so at a thorough disadvantage.

The reality of the Battle of Okeechobee is that a mere ~400 Seminole warriors fought not only for their lives, but their homeland, culture, and families against 800 trained military soldiers and officers. They employed incredibly complex and well thought out guerilla warfare tactics to compensate for their disadvantage in numbers. The Seminoles knew the landscape and drew the US forces into the swamp where they were better equipped to attack, then melt back into the scenery.

In a 2017 Seminole Tribune Article, former Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Exhibits Curator Rebecca Fell-Mazeroski explains more about the Seminole strategy, stating: “The landscape the troops traversed to reach the Seminoles was 5’ tall sawgrass, muddy, uneven, and full of dying vegetation. But, the area directly in front of a stand of trees was mown and clear of saplings. After the battle, Taylor’s men found notches in the tree branches where Seminole warriors had rested their guns. That stand of trees also provided two convenient escape routes to the west and east.”

2015.6.23142, ATTK Museum

Beyond the Battle

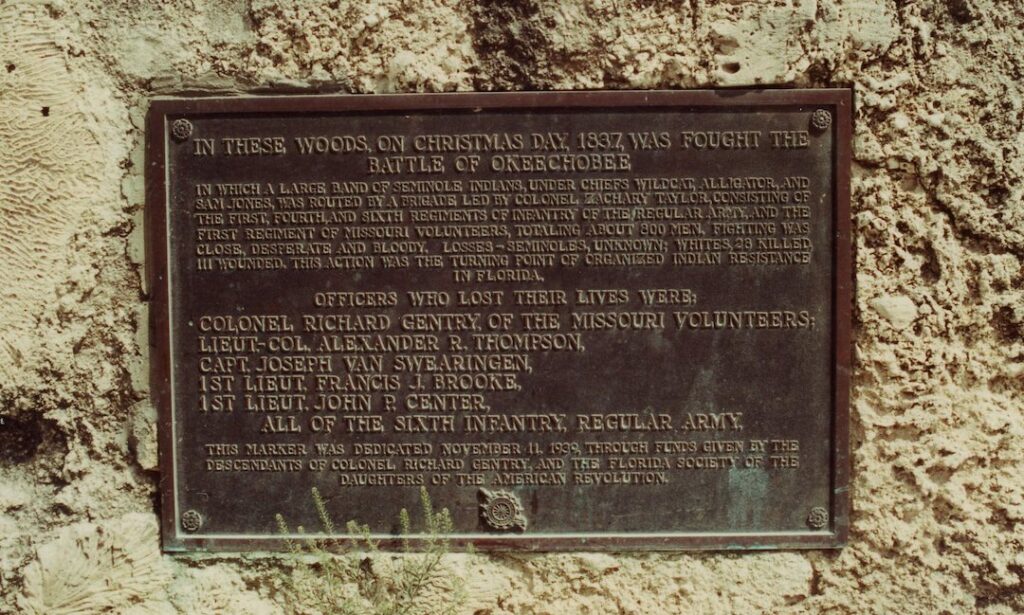

The Battle of Okeechobee has been remembered as a bloody, desperate conflict between US forces and Seminole guerilla fighters. Above, you can see a plaque at the Battle of Okeechobee Battlefield Monument placed in 1939 with funds from the descendants of Colonel Richard Gentry and the Florida Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Note how the number of Seminoles lost is listed as “unknown” and the marker refers almost entirely to the US Army losses. Even over one hundred years after the conflict, the prevailing narrative of centering US forces over Seminole resistors continued, as evidenced by this plaque.

But, Seminoles prevailed in the Battle of Okeechobee in their intention, even if it did not make it to the newspapers. Thus, it is important when reframing these historical moments in your mind to remember: who drove the narrative for the history books? Victory in the US frame of mind was to be the last one on the battlefield; no matter that they lost more casualties and didn’t gain any surrendering Seminoles. The United States was desperate for a win and accepted the victory at face value. Colonel Zachary Taylor came out of it with military accolades and earned himself the nickname “Old Rough and Ready.” Taylor would become the 12th President of the United States of America.

For the Seminole, the battle was a diversion of sorts. There was no winning, only survival. It allowed the non-fighting camp members, women and children, to flee to safety. Once their families and vulnerable were safe, the Seminole warriors abandoned the pitch and escaped to safety themselves. Looking back, the Battle of Okeechobee is a stark example of the Seminole drive to survive, and to keep their families, culture, and homes safe.

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, two sons, and dog.