Mystery at Fort Marion

What better way to start spooky season than with a mystery? This week, join us to explore the Mystery of the Escape from Fort Marion. During the Seminole War, Coacoochee (Wild Cat) famously escaped this prison, and went on to continue his fierce leadership and resistance to U.S. control. But, how did he do it? Today, we will look at the historic context of his escape, who was interned at Fort Marion, Coacoochee’s own words, and possible theories. Much like the legend of Sam Jones, the Mystery at Fort Marion has taken on a life of its own over time. There are many conflicting historical reports, stories, and perspectives about the escape. Read more below to learn more about theories, thoughts, and even Coacoochee’s own story of escape!

Aerial of Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) circa 1942, Rahner/State Archives of Florida

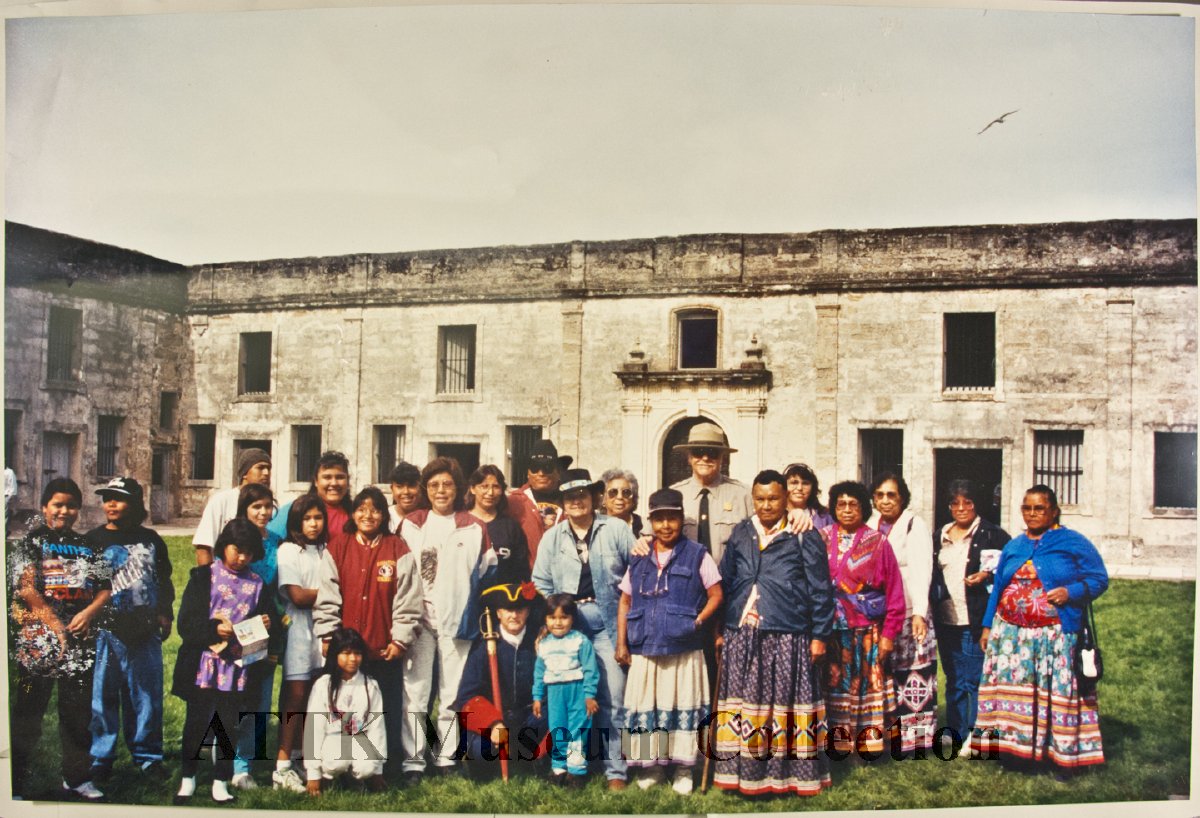

In our featured image this week (ATTK Museum, Catalog GRP1890.39), a group of Seminoles visit Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) around the early 2000s. Patricia Wickman stands in the center. Wickman organized the “Time Travel Tour,” sponsored by the Seminole Tribe’s Department of Anthropology & Genealogy. According to a Seminole Tribune article about the tours, “The Time Travel Tour provided the Seminoles an opportunity to explore their culture and retrace the steps their ancestors had been forced to travel years before.”

Also featured in the image are Roger Smith and his wife to his right; Louise Gopher in the white track suit to the right of the kneeling soldier; and Happy Jones standing to the left front of Wickman, wearing a black cap and sleeveless denim vest and long skirt with a blue patchwork band. Today, Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) is open to the public as a National Monument.

Historical Context

Spanish settlers began construction of the fort in 1672 to defend their colony of La Florida and the Atlantic trade route. The impressive fort, made with coquina, replaced a series of wooden structures that were continuously under attack. By the Seminole War period, the fort had changed hands a number of times, shifting from Spanish to British, back to Spanish, then to United States control. Under control of the United States, it was renamed Fort Marion. During the Civil War, Fort Marion became an essential base of operations for the Confederacy after Florida seceded from the Union. Eventually, Confederate forces abandoned the fort for a more centralized location, and the Union army was able to peacefully occupy the fortification for the rest of the war.

Coachoochee’s imprisonment at Fort Marion fell during what scholars term as the Second Seminole War, from 1835-1842. It was “the longest and most costly war between Native Americans and the United States. For every four Seminoles deported, the US Army killed one Seminole, lost three US Army soldiers, and spent $32,000. In today’s dollars, for every Seminole person shipped west, the government spent the equivalent of $8.5 million.” Seminoles, on the other hand, recognize the entire Seminole War period as one large conflict, calling it “the Long War.” Lasting from 1812 through 1858, during the Long War “There was never truly a peace for the Seminole.” During this time, Seminoles regularly faced aggression, violence, and pressure to leave from settlers, militia groups, the U.S. army, slave catchers, and lawmen.

Indigenous Internment at Fort Marion

Fort Marion was used as a prison multiple times in its history, famously interning large groups of Indigenous people. During November and December 1837, the United states imprisoned over 230 Seminoles at Fort Marion. The majority were taken under the flag of truce. A number of Seminole leaders, warriors, and their families had gathered at Fort Peyton intending to negotiate with U.S. forces. Just seven miles south of St. Augustine, the group was quickly surrounded by troops under the command of General Jesup and transported to Fort Marion. Constantly under guard, the Seminole prisoners were confined to the west side and southwest corners of the fort. Sickness was rampant, and many struggled with ill health during their confinement. After Coacoochee’s escape, U.S. forces transported the remaining Seminole prisoners to Fort Moultrie in South Carolina.

Beyond the Seminole War period, Fort Marion was again used as a space for Indigenous internment later in the 1870s and 1880s. Between 1875 and 1878, 74 prisoners from Fort Sill in Oklahoma were imprisoned at Fort Marion. Many were survivors of the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, where a peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho village was attacked by units of the Colorado Volunteer Militia. Those imprisoned at Fort Marion came from five different tribes; “there were 33 Cheyenne, 27 Kiowa, 11 Comanche, 2 Arapaho, and 1 Caddo. Included among the prisoners were 10 Mexicans who had been assimilated into these tribes.” Although these prisoners would eventually move on from Fort Marion, more Indigenous prisoners, predominantly Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apaches, would arrive in 1886 for a third period of Indigenous internment. Below, you can see a group of “Western Indians” interred at Fort Marion in 1875.

GRP1891.57, ATTK Museum

Who Was There?

Osceola

Arguably the most famous Seminole warrior in history, Osceola was interned at Fort Marion during the same time as Coacoochee. In October 1837, General Thomas Jesup captured Osceola under the white flag of truce. Osceola was a fierce tactician and Jesup utilized underhanded means to capture the warrior. He had eluded capture for years, and successfully led his army to safety multiple times. Osceola was in St. Augustine as part of wartime negotiations when he was taken prisoner in 1837. Osceola was then imprisoned at Fort Marion, under Captain Pitcairn Morrison of the 4th U.S. Infantry. In December of 1837, Coacoochee orchestrated his escape from Fort Marion. Unfortunately, by this point Osceola was in declining health. He was too weak to participate in the escape.

Soon after, the United States transferred Osceola and 237 other interned Seminoles to Fort Moultrie in South Carolina. It is believed that this transfer was a result of the successful escape by Coacoochee, and fear on the U.S. part that another escape was imminent. Osceola spent his final month imprisoned at Fort Moultrie, passing away in January of 1838.

He sat for a number of portraits in his final days. Below, you can see a portrait of Osceola by George S. Catlin, 1838. Catlin painted Osceola only days before his death at Fort Moultrie in South Carolina.

State Archives of Florida

Emathla (King Phillip)

Emathla (King Phillip), was a respected Seminole elder and leader. He was also Coacoochee’s father, and brother in law to Micanopy. Along with Coacoochee, Emathla was firmly against Seminole removal, and worked tirelessly to resist the Indian Removal policy and keep Seminoles in Florida. In September 1837, General Hernandez captured Emlatha while camped near the ruins of the Dunlawton Plantation. Unfortunately, his capture and subsequent imprisonment at Fort Marion was used to manipulate Coacoochee and Osceola into coming under the flag of truce to negotiate. This eventually resulted in both of their capture and imprisonment. Although Coacoochee would escape, Emlatha was elderly and could not participate in the prison break. Emlatha died in 1839 during transportation west on the Trail of Tears. Below, you can see a portrait of Emlatha by George Caitlin. Emlatha sat for the portrait in 1838 at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina.

George Catlin, Ee-mat-lá-, King Phillip, Second Chief, 1838, oil on canvas, 29 x 24 in. (73.7 x 60.9 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.302

Coacoochee (Wild Cat)

The wily hero of this mystery, Coacoochee was a fierce front-line leader during the Seminole War period. Coacoochee led Seminoles to victory in several conflicts with the United States. American leaders described him as “the most dangerous chieftain in the field.” Born in 1810, Cocacoochee was the son of Emlatha and nephew to Micanopy. A well-respected warrior, the story of his escape from Fort Marion is only a piece of his story. The most well-known version of his escape documents that Coacoochee orchestrated the flight of over twenty Seminole prisoners from Fort Marion in November 1837. Only Osceola, who was too sick to participate, was left behind despite Coacoochee delaying to try and give Osceola time to get better. But is that the whole story?

State Archives of Florida

The Escape and Theories

Coacoochee escaped in November 1837. But, historians still debate the details of his escape. Some sources claim that Coacoochee escaped with twenty other Seminole prisoners. In the official report right after the escape, U.S. Army official records show communication with the fort commander stating on November 30, 1837, that “I have to report the escape last night of twenty Indian prisoners, including two women” (Porter 119). But, in a later retelling, Coacoochee would note that only he and friend Talmus Hadjo would be able to break free of Fort Marion.

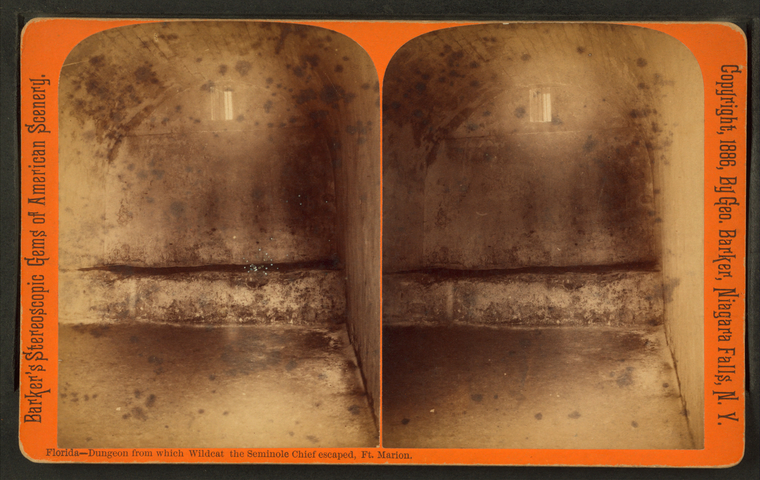

U.S. Army records posited that Coacoochee escaped through a small window in his cell, a room in the southwest corner of the fort. They had deemed the cell inescapable. Below, you can see an image taken in 1886 of the dungeons where Wild Cat escaped. Note that the window is both incredibly high up and incredibly small of an opening. Contemporary historians debate if it would even be possible for someone to escape via such a small opening. Other floated theories include the duo (or more?) bribing the guards, and simply walking out the door.

Willie Johns, late Seminole historian and part of the Wild Cat clan, would state in 2020 that “I don’t think [historians] really know. But there are three trains of thought,” Johns said. “They either crawled through an opening in the cell after losing enough weight by fasting; they were never held at Fort Marion in the first place; or the cell was accidentally left open and they walked out.” Although on the record as leaning towards the “cell being left open” theory, Johns would feature Coachoochee’s escape through the cell window in his 2020 book with John and Mary Lou Missal, What We Have Endured.

The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1886.

Coacoochee’s Account of the Escape

Coacoochee himself describes starving himself for five days to fit through the window (Porter 117). In this account, Cocoochee and Talmus Hadjo cut up feed bags to create a rope, squeezing through the incredibly small window, and dropping 25 feet to the ditch below (Porter 117-118). They then fled on foot, eventually finding a mule that Talmus Hadjo could ride. The fall injured Talmus Hadjo, resulting in a lame leg that hindered his ability to walk. The official U.S. Army account mentions iron bars on the window, although this is not featured in Coacoochee’s. Below, you can read an excerpt from Coacoochee’s account of the escape. It reads:

“I took the rope, which we had secreted under our bed, and mounting upon the shoulder of my comrade, raised myself upon the knife worked into the crevices of the stone, and succeeded in reaching the embrasure. Here I made fast the rope, that my friend might follow me. I then passed through the hole a sufficient length of it to reach the ground upon the outside in the ditch…. With much difficulty I succeeded in getting my head through; for the sharp stones took the skin off my breast and back. Putting my head through first, I was obliged to go down head-foremost, until my feet were through, fearing every moment the rope would break, At last, safely on the ground, I awaited with anxiety the arrival of my comrade.”

Coacoochee would continue to fight for the Seminole people to stay in Florida as long as he was able. He was instrumental in the famous Battle of Okeechobee, where Seminole forces came up against Colonel Zachary Taylor on December 25, 1837. The U.S. forced Coacoochee to surrender in 1841. They transported him to Fort Gibson in Oklahoma’s Indian Territory soon after. He would die of smallpox in Mexico in 1857. But, his escape and the legacy of his leadership would have a lasting impact on the Seminole story and history of resilience against unbelievable pressures.

So, how do you think he did it? Let us know what you think about the Mystery of the Escape at Fort Marion in the comments!

Additional Sources

The author accessed these sources digitally. Page reference numbers may not align with paper and hardback copies.

Porter, Kenneth W. (1943) “Seminole Flight from Fort Marion,” Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 22 : No. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol22/iss3/3

Author Bio

Originally from Washington state, Deanna Butler received her BA in Archaeological Sciences from the University of Washington in 2014. Deanna moved to South Florida in 2016. Soon, she began working for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Deanna was the THPO’s Archaeological Collections Assistant from 2017-2021. While at the THPO, Deanna worked to preserve, support, and process the Tribe’s archaeological collection. She often wrote the popular Artifact of the Month series, and worked on many community and educational outreach programs. She lives in Fort Myers, FL with her husband, son, and dog.