Survival in the Swamp: Bloody Battle of the Wahoo

Welcome back to the latest installment in our Seminole Spaces series! In this series, we explore the places and spaces that are important to Seminole history, tourism, and culture. This week, we are looking at one of the bloodiest battles of the Seminole War period: the Battle of Wahoo Swamp. This battle marked a major shift in the Seminole War, one that would have long-reaching consequences.

It should be taken into consideration when reading this blog that most of the information about the lead up to and Battle of Wahoo Swamp is based off of U.S. military records, letters, and maps. Even the Seminole losses and injuries are unknown.

On the Wikipedia page for the battle it is listed as an “American victory.” When looking at history, it is our responsibility to peel back the layers and complexities around the narrative. The U.S. Army wrote the history books for a long time, denying Seminoles and other Indigenous people a voice. While it is not useful now to determine if the Battle of Wahoo Swamp was an “American victory” or a “Seminole victory” it is important to remember that at the end of the battle, Seminoles accomplished their goal. They survived.

Where is Wahoo Swamp?

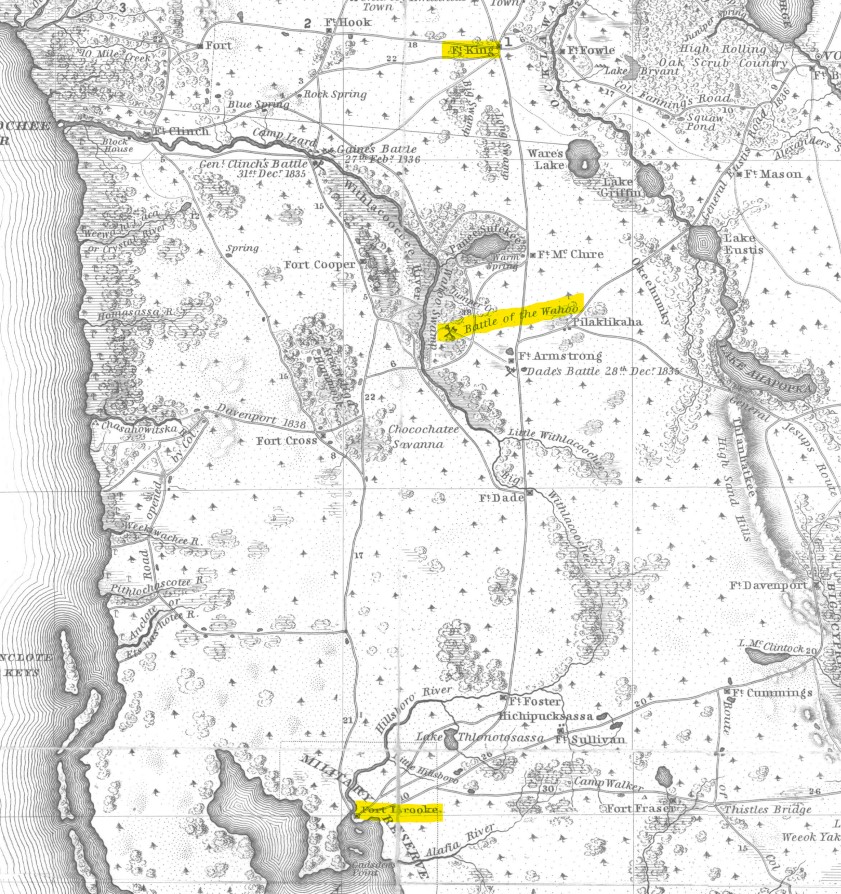

Wahoo Swamp is located in Central Florida, sandwiched between two of the most important forts of the Seminole War. It is only 50 miles to the northeast of Fort Brooke in Tampa, and 35 miles south of Fort King in Ocala. Below, you can see an excerpt from “A Map of the Seat of War in Florida” by Captain John Mackay and Lieutenant J. Black, U.S. Topographical Engineers, 1839.

Fort King, Fort Brooke, and the Battle of Wahoo Swamp have been highlighted. You can clearly see that Wahoo Swamp is directly in line with the road where troops would be travelling and transporting supplies. There were a significant number of other forts scattered throughout Central Florida during this time, with the intention being to place pressure on Seminoles. The Dade Massacre, which is commonly pointed to as the start of the Second Seminole War, is just to the southeast of Wahoo Swamp.

Fort Brooke and Fort King were important miliary strongholds for the United States military during this period. They were both constructed to suppress action taken by Seminoles, curtail their resistance, and monitor Seminole movements at Silver Springs. Fort Brooke was intended to enforce the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, which confined Seminoles to a reservation. This treaty was never fulfilled. It became a bustling military hub and was also the focus of many Seminole guerilla warfare attacks.

Fort King was a major military base in the 1830s, particularly playing a large role in Seminole removal. It was the site of a number of negotiations between Seminoles and U.S. Army leaders leading up to and during the Second Seminole War. This included Osceola’s famous interaction with Indian Agent Wiley Thompson, which resulted in Osceola killing Agent Thompson outside the fort on December 28, 1835.

Why Wahoo Swamp?

Wahoo Swamp and the area around the Withlacoochee River had a robust number of Seminole villages. They routinely hid their cattle in the swampland, where it was much more difficult to navigate by the unprepared Army. Due to the natural terrain, Seminoles were easily able to hide their gardens, villages, foodstuffs, cattle, and other supplies.

It was a well-known area for Seminole settlement at the time, making it a target for the U.S. Army at this point in the war effort. But the U.S. Army also was unfamiliar with not only the terrain but also how to survive in it, deterring their efforts. The Battle of Wahoo Swamp was not the first time they had attempted to attack this area, with the Battle of the Withlacoochee occurring December 1835.

The set-up

Prior to the Battle of Wahoo Swamp, tensions between Seminoles and U.S. Army combatants had continued to rise. The Second Seminole War had “officially” begun the previous year in 1835, although for Seminoles it was one long war. By mid-1836 the U.S. Army was struggling in their campaign against the Seminoles. Multiple forts had been abandoned, including Fort King and Fort Alabama.

There were also a number of Seminole raids and attacks on other forts throughout the spring and summer of 1836. This included Fort Barnwell in Volusia, Fort Drane, Fort Alabama, and a blockhouse on the Withlacoochee River. On July 23, 1836 Seminoles also attacked the Cape Florida Lighthouse to the south, burning it down. General Duncan Lamont Clinch, who had been placed in charge of Army units in Florida, resigned his commission after Seminoles burned the sugar works on his plantation near Fort Drane. He would leave the territory completely.

Soldiers in the summer of 1836 also saw sweeping illness decimate their ranks. At least one fort, Fort Drane, was abandoned entirely due to sickness. Those soldiers retreated to Fort Defiance but were attacked by Seminoles while journeying there. By the end of August, Fort Defiance was also abandoned.

All of these struggles and mishaps on the side of U.S. forces spurred action from Congress, who went on to allocate another $1.5 million for the war effort. It should be noted that the Second Seminole War was the deadliest and costliest of the American Indian Wars. Richard Keith Call, who had led the Florida volunteers, was also appointed Governor of the Territory of Florida in March 1836. Call subsequently began a campaign aimed at rousting out the Seminoles around the Withlacoochee River, where Clinch had previously failed. It was this campaign in the fall of 1836 that could culminate in the Battle of Wahoo Swamp.

“You have guns and so have we. You have powder and lead, and so have we. You have men and so have we. Your men will fight and so will ours, till the last drop of the Seminole’s blood has moistened the dust of his hunting ground.”

—Osceola, February 2, 1834, statement to Brigadier General Duncan L. Clinch

November 17-18th, 1836

Governor Call had to delay his campaign on the Withlacoochee River due to supply and troop delays until the late fall. In October, Call would make his first attempt at fording the Withlacoochee River. It quickly failed due to flooding which made the river impassable. Other accounts refer to the attempts on October 10th ending due to Seminole gunfire. Call and his command would leave Fort Drane again on November 10th. They would cross the Withlacoochee on November 13th, losing four soldiers during the crossing and burning abandoned Seminole villages along the way. Call split his forces along the two banks of the river and moved south.

Although the Battle of Wahoo Swamp mostly refers to the battle on November 21st, there were two interactions in a few previous days which could fall under the umbrella of this battle. On November 17th a regiment of Tennessee Militia Volunteers would find a Seminole camp next to a hammock, engaging with them immediately. The quick skirmish pushed into the hammock, and the Seminoles fled leaving their camp and supplies. Approximately twenty Seminoles died in the fight.

The next day on November 18th the Army gave chase, engaging with a larger group of Seminoles on the east side of the swamp. The skirmish consisted of about 600-700 Seminole warriors, who again retreated. It was after this that the U.S. decided to recall the other half of their troops from the west side of the Withlacoochee, and march on Wahoo Swamp.

The Battle of Wahoo Swamp on November 21st, 1836

Governor Call began his march on Wahoo Swamp on November 21st, 1836. His forces, as described by him, consisted of about 1,830 men, cobbled together from regulars, Tennessee Militia Volunteers, Friendly Creeks, and the Florida Militia. Formed into three columns the group advanced into the Swamp, coming under Seminole fire. As the U.S. Army responded, the Seminoles retreated across a small river. It was at this point that the Seminoles took up a strong defensive position.

The Creeks, led by Major David Moniac, were the first to catch up to the Seminoles, as the rest of the troops were struggling against waist high mud and were unable to maneuver their horses. Moniac, who was Creek, was the first Native American to graduate from West Point. Moniac was quickly shot and killed while trying to cross the river, and the Creeks were soon in desperate need of reinforcements.

A bloody battle ensued, with the U.S. side only surviving once their full forces could make it to the river. They chose not to push across the river itself and believed it would result in heavy losses. The Seminoles left to the south, and again the U.S. decided not to pursue due to the difficult terrain and lack of supplies. Both sides suffered heavy losses, making the Battle of Wahoo Swamp one of the bloodiest battles of the Seminole War.

The Fallout

When we began this post, we noted that it is especially important when looking back at history to drill down into the narrative. Who is recalling this history? Most of the accounts around the Battle of Wahoo Swamp were given by the U.S. Military, and you may recall that they determined it an “American victory” despite accomplishing none of their goals.

But the reality is much more nuanced. Seminoles deliberately planned their retreats, luring troops deeper into Wahoo Swamp. They intentionally picked the area for its natural terrain, which they knew would give them the advantage. These Seminole warriors were also protecting a nearby camp where women, children, and elders had taken shelter. At the end of the battle the U.S. did not breach the river, and the Seminole survived.

Following the unsuccessful, aggressive push into Seminole territory Governor Call was relieved of command by President Jackson. What Call had intended to be an easy victory to impress President Jackson ended in defeat. He was replaced by the infamous General Thomas Sidney Jesup, who would later break the military code of honor by arresting Osceola under a flag of truce. This battle had a long reaching impact, as the subsequent shakeup of command of the U.S. side would place one of the most brutal of their wartime generals at the helm.

Additional Resources

The Battle of Wahoo Swamp, Seminole History Stories by the STOF-THPO

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Candice Shy Hooper

Thank you for this great summary of this important battle.