Spotlight on History: The Life of Chief Chipco

Welcome back, and happy Friday! This week, join us for the first installation of a brand-new series: Seminole Spotlight. In this series, we spotlight a person, tradition, or item important to Seminole culture and history. Today, we are looking at Echo Emathla Chipco, also known as “Chief Chipco,” and his nephew Chief Tallahassee.

Chipco was also known as “Chupco”, “Chopco” and occasionally “Chopka” in some documents. The deviation in spelling is most likely a white settler translation error, as his descendants still go by “Chupco.” For the purposes of this blog post, we have chosen to stick with the “Chipco” spelling, as if you were looking for further documentation on his life, this would be the best avenue for finding it.

In our featured image, you can see Lena Gopher, Shule Snow Jones (with baby), Mary Jo Jones, and Parker Jones standing around the monument honoring Chief Tallahassee’s camp near Lake Wales, Florida in 1958 when it was dedicated. The inscription on the monument reads: “On Lake Pierce is the site of the Seminole camp of Chief Tallahassee, who succeeded Chief Chipco, leader of the Creek Seminoles. Chief Chipco is buried nearby. The village was abandoned about 1890.”

Echo Emathla, “Chief Chipco”

A Red Stick Creek, Echo Emathla Chipco was born around 1805 in Alabama. After the War of 1812, he and his family would flee to Florida following the Creek defeat. Like many of this era, his life was one marked by loss at the hands of the Indian Wars. His own father would die in 1818 in the “First” Seminole War on the Suwanee River against Jackson’s troops.

As he grew, Chipco stayed mostly within the Tampa and Central Florida Region, although the war would necessitate him moving to evade capture numerous times. Chipco became a respected leader, and vocal opponent to Indian Removal. During the wartime period, Chipco would head a band known as the Tallahassee Creeks settled along the Kissimmee River. Famously, Chipco is recalled having said that he would “never emigrate and that he did not fear all the ‘Crackers’ in Florida” (Knetsch et al 2018).

By 1835 Seminoles were under incredible pressure and threat of violence, removal, and extermination by the U.S. Military and settlers around them. Travelling with Halpatter Tustenuggee’s camp at this point in time, Chipco would be present for the Dade Massacre, which would spark what history remembers as the Second Seminole War. Forty-four years after the battle, “Chipco told [a representative of the Office of Indian Affairs] that he was one of the leaders of the attack on Major Dade’s forces” (Hannel 2019). Chipco would spend the rest of the Seminole War fighting against removal, acting as a staunch opponent and guerilla leader. He would retreat south into the Everglades during the Third Seminole War, focusing on evading capture rather than going on the offensive. Following the wartime period Chipco and his camp would return to Central Florida.

A Trade Leader

Chipco was well respected and known for having many trade partners and contacts built throughout the decades. During the Seminole War period, these trade partners would relay information to Chipco and his camp, allowing them to evade capture. In 1956 Albert Devane would research Chipco and Tallahassee, publishing his article in the Tampa Tribune. He writes that “In 1856 William Collins, son of Enoch and grandson of Samuel Knight, had established friendly relations with Chipco and his band. He heard of plans to capture Chipco and his people, [and] travelled on horseback at night and advised Chipco of the plans. A boat company of Florida militia had transported boats to a point near [Lake Hamilton], concealing them while awaiting nightfall to make the capture…. To their surprise there was no one on the island – the Indians had abandoned camp and fled” (Devane 1956).

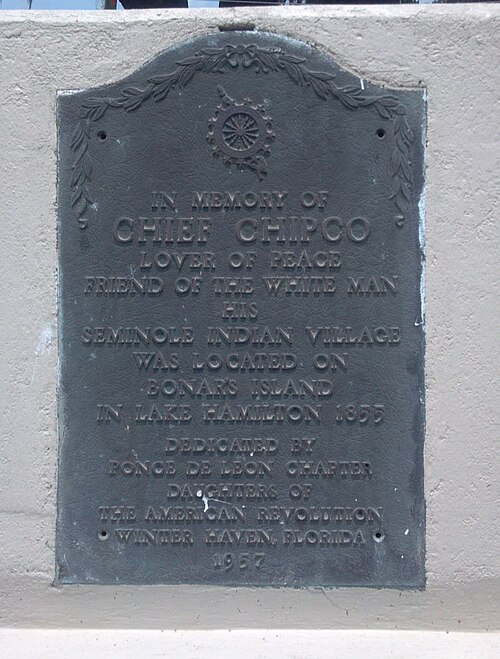

Chipco’s goodwill with trade partners and settlers around him would continue after the war period was over. In fact, his reputation was “so well respected that the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a roadside marker to him in 1957 near his old home in Lake Hamilton” (Knetsch et al 2018). You can see this marker above.

This is the same camp that Devane recalls in his 1956 writings above. He is often referred to as a “friend” of the white man in text, predominantly due to his willingness to trade and engage with settlers. Despite the horrors of the Seminole War, even at the hands of settlers, Chipco would have good relations with those around him into his old age.

Chipco’s Village

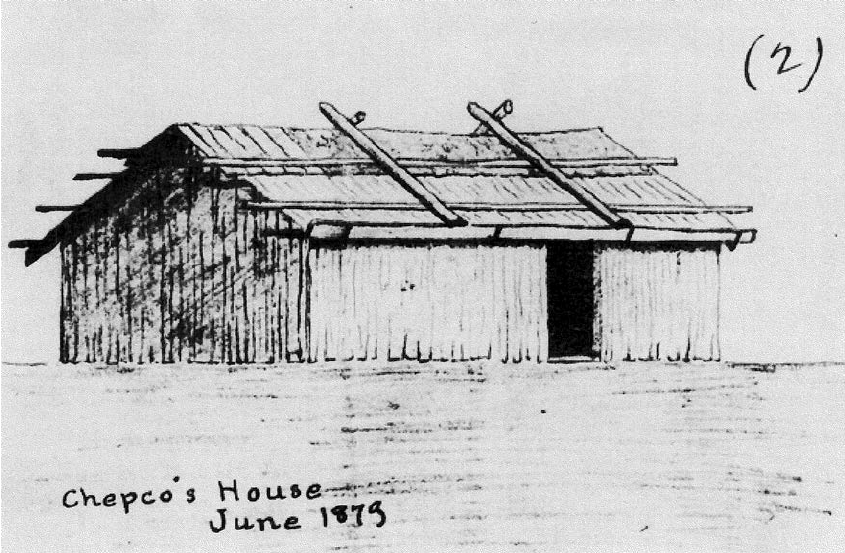

Returning from the Everglades following the Third Seminole War, Chipco would set up his camp back in Polk County, near Lake Pierce. In 1879 Lt. Richard Henry Pratt was sent by the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs to investigate the circumstances of the Seminoles of Florida. His report was revived and annotated by William C. Sturtevant in 1956. He described Chipco’s village as sitting at “a slight elevation in the piney woods, in vicinity of clear, beautiful lakes,” with about 10 buildings “equal in comfort to those of many of their white neighbors.” Below, you can see a drawing from that trip. Notably, Chipco lived in something more reminiscent of a log cabin, instead of the typical Seminole chickee.

Pratt also noted that Chipco’s village was rich in resources, with an array of crops hidden in the dense hammock. “The land was rich and crops equal in appearance to any I saw in the state. Each family had its separate patch of corn, rice, sweet potatoes, sugar cane, and melons. Old Chipco had a few stalks of tobacco. The cultivation was perfect: not a weed was to be seen.” Pratt also noted a number of hogs, ponies, and a few cattle (Tampa Tribune, July 29, 1990). Chipco passed away peacefully at his Lake Pierce village around 1881.

Chief Tallahassee, Chipco’s nephew

Chief Tallahassee and Legacy

Shortly before his death, Chipco would pass along the leadership of his camp to his nephew, Tallahassee (seen above). He wears buckskin pants under a bigshirt, with two sashes across his chest in this image. Tallahassee would lead the village in its final decade, before it was abandoned around 1890. Tallahassee would continue Chipco’s example and trade vigorously with those around him, all the way to Tampa. Although we do not know the exact reason the village was abandoned, some educated guesses include both increased white settlement in the area and population decline of the village.

Chipco and Tallahassee’s descendants would become part of the Seminoles of Florida. Today, you can even find Chipco’s name on the Fort Pierce Reservation. Chupco’s Landing Community Center on the Fort Pierce Seminole Reservation was built in 2014. Sally Chupco Tommie, the late matriarch of many residents of the Fort Pierce Reservation, was Chipco’s daughter.

Chipco Township and Legacy

Chipco’s name has been attached to at least one white settlement, Chipco Township. Located near Dade City, the former settlement was less than six miles from Fort Dade #2. It was established in 1849, although it didn’t rise to prominence until after the civil war. One of Chipco’s camps was located nearby prior to 1850 and up through 1866. He traded heavily in the area, apparently to such a degree that the town was named after him.

In 2020 Seminole Tribune article Dade City residents Karen and Eric Hannell established a marker commemorating the township. According to Eric Hannell “We surmise that the town was known as Chipco at least by the late 1870s.” The town would bustle throughout the late 1800s. It “thrived when Tampa Bay was little more than a trading post. Chipco boasted a school that doubled as a church on Sundays. It also had a thriving general store, planing mill, train depot and a grist mill that was said to be the first in the county.” Unfortunately, the Great Freeze of 1895 would devastate the town, and it was completely removed from the maps by 1909. It is now a Florida Heritage Site.

Additional Sources:

DeVane, Albert. “Chipco and Tallahassee Led Seminole Remnant in Florida.” The Tampa Tribune, 15 July 1956, p. 15D.

Hannel, Eric (2019) “Amnesia, Anamnesis, and Myth-Making in Florida: A Case Study of Chipco,” Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 98: No. 2, Article 5.

Knetsch, Joe; Missall, John; Missall, Mary Lou (2018). History of the Third Seminole War, 1849–1858. Havertown, Pennsylvania: Casemate Publishers.

- Pratt’s Report On the Seminoles in 1879. William C. Sturtevant. Florida Anthropologist. 9 (1): 1-24. 1956.